The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

December 5, 2016 by Katherine Olstein

Two Women Team Up to Revitalize Music from a Polish Shtetl

Shortly after scientist and musician David Goldfarb moved to Highland Park, New Jersey, in 1989, he joined the Conservative synagogue, where he met Milton and Frieda Frant, an outgoing older couple. Playing Jewish geography on the phone, his parents on the West Coast asked if he had come across anyone named “Milton Frant” because, he should know, their families were related by marriage.

Years later, at the outset of clarinetist Goldfarb’s first class at KlezKamp 2008, instructor Adrianne Greenbaum handed out sheet music, saying that it was from the Frand Klezmorim and naming Milton Frant’s daughter, Sharon Frant Brooks, as her source for the historically significant arrangement. This meant that the music Goldfarb was about to play was from his family’s past.“I turned white as a sheet because I didn’t know any of this,” says Goldfarb. “So when I came home I contacted Sharon and I said, ‘You knew I play music, why the heck didn’t you tell me?’”

Adrianne Greenbaum and David Goldfarb with Sharon Frant Brooks and her father, Milton Frant (z”l), in his Highland Park living room a few weeks before the concert, which celebrated his 95th birthday.

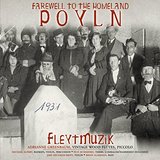

In fact, Sharon Frant Brooks and Adrianne Greenbaum had just set out on a quest to revitalize the Jewish community of Dubiecko [doob-YETS-ko], Poland, chiefly through the Frand family’s music. Last July they celebrated a milestone in that journey with the release of “Farewell to the Homeland Poyln,” by Greenbaum and her klezmer ensemble, FleytMuzik, recorded live at a gala Goldfarb spearheaded at the Highland Park Conservative Temple.

“Because the Frand band had both a flutist and piccolist, our public would be treated to a true revival,” says Greenbaum, who plays vintage flutes on the album. The rest of the ensemble features, Pete Rushefsky, cimbalom; Michael Alpert, violin and badkhn [jester-entertainer at Ashkenazi Eastern European social events]; Jake Shulman-Ment, violin and Brian Glassman, bass.

The Dubiecko Drama Club, 1931. Moishe Marshaluk, the badkhn, is in the first row above the stone engraved with the year.

“The music that I culled, selected and transcribed from the Frand folio represents a very important volume of history that was, until now, partly or totally unknown,” says Greenbaum. “The selections on the CD are all instrumental, although Michael Alpert artfully sings his own poetry in our concert wedding set, playing the role of Moishe Marshaluk, a well-known teacher and the Frand Klezmorim badkhn.”

As FleytMuzik’s leader for well over a decade and professor of flute at an all-women’s college for over four decades, Greenbaum takes pride in her influence as a female with a strong voice in music.

WHAT CATALYZED THE QUEST BY THESE TWO WOMEN?

Invited by the Polish Paralympic Committee to work at an event in northern Poland in 2006, Brooks and two cousins who accompanied her also visited Dubiecko, Przemyśl and Dynow in the southeast sector of the country.

Having learned that a Torah from Dubiecko remained in a library case in Dynow, the cousins tracked it down, and found the relic in a deplorable state. Once home, Brooks decided to have it moved, preserved and displayed appropriately in its place of origin.

But that plan proved impossible, as did a number of alternative projects. “Everything I did hit a brick wall,” she says. “Then I remembered I had this music that had belonged to my grandfather.”

In 1925, Brooks’s grandfather, Chaskel Frand, fled Poland for the U.S with his violin and a sheaf of handwritten music for flute stuffed into its case. After he immigrated to Israel, the violin and the music meandered around the family, got separated and dropped out of awareness until Brooks’s daughter, Danielle, started taking violin lessons, and her father’s sister decided to mail the handwritten collection to them.

Brooks set about searching for Jewish musicians who would commit to playing the Klezmorim’s compositions, posting their availability on Jewish music listservs.

Of 38 respondents, the most enterprising were Greenbaum, professor of flute at Mount Holyoke College, and Hankus Netsky, founder of the New England Conservatory’s Klezmer Conservatory Band. The group performed Klezmorim pieces in three concerts in Boston in 2011, and Mr. Netsky organized a year-long project about the Frand family music at the Yiddish Book Center. “Personally, the music is all about the family,” says Brooks. “It is signed and dated by them. One piece was written by my dad’s uncle, Naftali, who was killed in World War I.”

The 60-page folio of Jewish melodies and Polish folk tunes for flute was a magical find for Greenbaum, and she debuted selections from it at Brooks’s temple in Flemington, New Jersey, in August, 2009.

Two samples of Frand Klezmorim music from “Farewell to the Homeland Poyln” that Greenbaum recommends are: Track 1, because “it introduces the title and moves into what is possibly a unique Chasidic tune, probably known only to Dubiecko Jews and their rebbe”; and Track 10, “a truly Jewish tune for the groom.”

Adrianne Greenbaum with Rzerzow group, Dubiecko, 2010, funded in part by a Mt. Holyoke grant. Photo courtesy of Marcia Shiffman.

The concert in Flemington raised enough money for the pair to rededicate the Dubiecko Jewish cemetery, and for Greenbaum to perform with Polish instrumentalists in Dubiecko, in two trips to Poland in 2010 and 2012. More concerts would follow in the US.

After the creation of Israel, there was little interest in hearing about the Pale until the early 2000s. The cut off from the older culture was willful, says Mr. Netsky. But that outlook had changed.

According to Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland who became instrumental in connecting Brooks and Greenbaum with Polish religious and secular communities, “You couldn’t talk about Jews for 50 years, but now you could.”

From right, Sharon Frant Brooks, Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the chief rabbi of Poland, and a member of the Polish Catholic clergy dedicating a memorial to the lost Jewish community of Dubiecko. Photo courtesy of Marcia Shiffman.

“Two things that impacted me most profoundly,” says Brooks, “were discovering that the family of a woman Adrianne and I came upon in Poland had saved the grandmother of a coworker of mine here in New Jersey. And reuniting my father with a childhood classmate whom we discovered at a Klezmorim performance of Adrianne’s in Manhattan and invited to our Highland Park concert. Ironically, the two friends died within 10 days of one another a few months afterward.”

Brooks and Rabbi Schudrich have approached the Jewish Fund for Poland in New York to raise funds for FleytMuzik to perform music from their CD in Dubiecko, for Brooks to erect a memorial monument in the Dubiecko Jewish cemetery and extend its walls, and for videographer Edward Alpern to complete his documentary about their collaboration.

Katherine Olstein is a freelance writer, editor and publications project manager, specializing in non-fiction print and digital prose.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...