The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

July 6, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Writer-Activist Meredith Tax Gives Voice to the Women Fighting ISIS

Meredith Tax

Lord of the Rings author J.R.R. Tolkien wrote that “courage is found in unlikely places.” This truism, of course, has been repeatedly proven, as places steeped in poverty, neglect, hunger, and even war have produced unexpected exemplars of valor and fortitude.

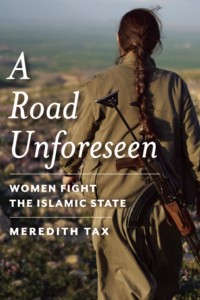

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Women, Tax reports, make up 40 percent of all organizations in Rojava, including those involved in local administration and decision-making. What’s more, every committee and oversight agency is led by one man and one woman, a conscious effort to promote female leadership and confront patriarchal cultural norms head-on.

Tax sat down with Lilith in late June to discuss activism, social change and women’s empowerment.

EJB: When did you become a feminist?

MT: I grew up in Milwaukee and my family was really sexist. As a kid in grade school I was told that a girl should not be too smart; my parents made it clear that no one would want to marry me if I did not tone it down. I was confused and didn’t understand why a boy wouldn’t want to be with someone who could help him with his homework! In sixth grade I started a petition to demand that girls be allowed to run for class president. As I got older I became more and more disgusted by the limited social possibilities for a girl like me. Reading saved me. Even before I left for college I’d read novels by Louisa May Alcott and plays by George Bernard Shaw that introduced me to feminism. I’d also read about the suffrage movement. Later, I went to Brandeis but even there, among a lot of smart women, our options were limited. After we graduated we could be teachers, social workers, or get a low-level job in publishing. I didn’t want that. I wanted to be a writer.

EJB: And you did! How did you make that happen?

MT: Indirectly! After college I got a Fulbright and moved to England. I’d never been politically active before, but I got involved in a British anti-war group called the Stop It Committee. That was the beginning of my involvement in left-wing politics. I stayed in England for four years, 1964-1968, but came back to the US to take a one-year job teaching English at Brandeis. That was the year Black students took over the school switchboard. Brandeis had just started an affirmative action program and had promised to create a Black Studies curriculum but they did not plan very well or develop a timetable for it. Many of the Black students were frustrated so they staged a takeover.

The Brandeis president at the time, Morris Abrams, [1918-2000] screwed up. He thought he was being strong and declared that he would not negotiate under pressure. A small group of us thought this was wrong, that he had to negotiate. As a result of speaking out I had a letter placed in my file that made me unemployable as a teacher. But by that point I no longer wanted to be an academic. I’d been part of a feminist group called Bread and Roses in Boston and I decided that I wanted to write a book about women’s history so that’s what I did.

I’d previously written Woman and Her Mind: The Story of Daily Life. It was published by the New England Free Press in 1970 and parts of it were later included in anthologies such as Shulamith Firestone’s Notes from the Second Year. The pamphlet was one of the first things written about sexual harassment.

My women’s history book, however, took a different turn. When I finished it and submitted it to McGraw Hill in 1976, it was rejected and they demanded that I return the $5,000 advance I’d received. I was working as a legal secretary at the time and was a single mom. I had no money so they might as well have asked me for $500,000. I ended up completely rewriting the book, The Rising of the Women: Feminist Solidarity and Class Conflict, 1880-1917, and it was finally published by Monthly Review Press in 1980.

EJB: Did you always need to have a day job to support your writing?

MT: Yes. When I was married to my first husband we lived in Chicago for a while. One of my jobs was as a nurse’s aide. The job gave me the chance to move out of the segregated society I’d grown up in. I learned a lot from African American and Latino/a co-workers including the importance of listening. My time in Chicago also included a stint at Zenith TV where I was responsible for doing 12 different operations a minute with a long-necked pliers and soldiering iron. Throughout this time, I was in political study groups and was doing left-wing organizing. When I moved to New York I did secretarial work and later taught at the Murphy Center of the City University.

EJB: Did you stay politically active after moving to New York City?

MT: After the Hyde Amendment cut off Medicaid funding for abortion in 1977, I got a call about an emergency meeting to discuss what this meant and how feminists should respond. So many people showed up that the meeting was moved to the Village Gate. Women from Planned Parenthood, NARAL, NOW, and socialist and radical feminist groups were there but no one knew what to do. Several other meetings followed and eventually resulted in the formation of CARASA, The Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, of which I was a founding co-chair. I stayed involved until I got a contract to write my first novel, Rivington Street, which came out in 1982. Its sequel, Union Square, came out in 1988.

EJB: Did you have any other political involvements during the 1980s?

MT: In 1986 Alix Shulman got me to join PEN. Norman Mailer was the President and he’d invited Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Schultz, to speak at the opening ceremony of that year’s conference. PEN had always been completely independent of the government and many people thought that inviting the Secretary of State to open the panel was inappropriate. Ed Doctorow and Grace Paley started a petition to give members a way to express their anger and it was supposed to be presented by Grace to Mailer before Schultz’s speech. But Mailer refused to acknowledge Grace and was quoted in the Village Voice saying that the Secretary of State was not going to be pussy-whipped by Grace Paley. It is worth noting that that year, 113 of the conference panelists were men and just 13 were women. And this was supposedly a conference of the world’s best writers.

The next day I chaired a meeting about gender disparity at the conference. Betty Friedan gave a fiery speech, which was reported on the front page of the New York Times. Shortly after this, we started the PEN Women’s Committee. Our emphasis was on bringing cultural diversity to the organization.

EJB: How did your international work begin?

MT: In 1989 I was on the PEN Board and went to my first international conference. By then I was itching to do broader women’s work. I’d become increasingly interested in the issue of voice, how different countries and cultures impact the ability of women writers to express themselves. I understood that if women can’t publish, other women probably can’t speak up either.

A year before the 1994 Beijing conference, a group of us had decided to start our own women’s organization. Our efforts became Women’s World Organization for Rights, Literature, and Development. Although Women’s World folded in the early 2000s, we had written a booklet, The Power of the Word: Culture, Censorship, and Voice, to bring to Beijing. It was about gender-based censorship and has been translated into 12 languages. We also worked to defend women writers, including the 2015 Nobel Prize for Literature winner, Svetlana Alexievich, Taslima Nasrin and others.

My book, Double Bind: The Muslim Right and the Anglo-American Left came out in 2012 and addresses the threat of Islamic fundamentalism.

As a result of this work, I was in constant contact with people all over the world. When I learned about ISIS [also called ISIL or Daesh], I became fascinated with how women were fighting them. The fact that women in Rojava are leading military battalions and that feminists are organizing to create a bottom-up participatory democracy in a war zone is incredible. It’s a story that needs to be publicized. A Road Unforeseen includes these women’s voices, as well as extensive research to give readers a deeper understanding of the region and the power players.

EJB: Why hasn’t the story of Rojava become better known?

MT: The Syrian civil war is complicated and most people don’t understand that Kurds live in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey and are leading the charge against ISIS. In addition, the Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK, which is on the US and European Union terrorist lists, is closely allied with the Syrian Democratic Union Party. This means that there’s a lot of nervousness about depicting the group in a positive light. Lastly, Turkey’s lobbyists in the US oppose giving positive coverage to the Kurds. We’re working to change that, obviously, and have formed a US-based group called the North American Rojava Alliance to get the word out. I’m hoping A Road Unforeseen will spread information and promote needed efforts to support these people.

EJB: Have any women’s or Jewish groups come to Rojava’s defense?

MT: Not yet, but I’m going to use the book to do outreach to them.

EJB: Are you optimistic about Rojava’s ability to hold on and, perhaps, defeat ISIS?

MT: No one knows what will happen if and when peace finally comes, but Rojava’s leaders are serious about pluralism and about creating and maintaining democratic, secular institutions at the base. More and more women are moving into positions of authority. With women comprising a leading role in the military struggle, I think it will be very hard to push them back into the home.

EJB: What can the Rojava model teach US feminists?

MT: I think we’ve learned that culture is terrifically persistent. We’ve also learned that if you fix the laws, you don’t necessarily fix people’s lived reality. Change takes more than new laws. Legislation is the beginning, not the end of organizing campaigns and real change can’t be top down. It has to confront and oppose patriarchal traditions at every turn.

Meredith Tax can be reached here.

Please wait...

Please wait...

Pingback: Meredith Tax speaks with Lilith about her lifelong... | Bellevue Literary Press