The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

April 12, 2016 by Pamela Rafalow Grossman

Gayle Kirschenbaum, “Accidental Therapist” for People Who Don’t Get Along With Their Mothers

It’s almost Passover—a time of renewal, of course, and a time to reflect on themes of freedom from enslavement.

There is a special Haftorah for the Shabbat before Passover. It’s the conclusion of the book of Malachi, and its last passage urges familial reconciliation—with a dire warning: “That you may turn the hearts of parents to their children, and the hearts of children to their parents, lest destruction smite your land.”

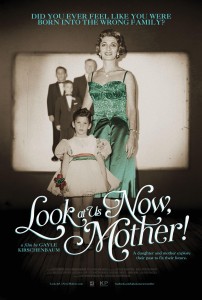

I approach an interview with documentarian Gayle Kirschenbaum with these things on my mind. Her newest film, the feature-length “Look at Us Now, Mother,” has won multiple awards on the festival circuit and is currently playing in New York, Los Angeles, and Boca Raton (see here for future screenings); it moves on to Kirschenbaum’s native Long Island in time for Mother’s Day. The film examines Gayle’s often-fraught relationship with her mother, Mildred, and her attempts to heal from familial pains of the past. The project evolved from a short documentary of Gayle’s called “My Nose” (2007), in which Mildred tries to convince her daughter that she dearly needs a nose job and Gayle agrees to go with her for consults with a few plastic surgeons—as long as she can film the process. (The conclusion: No one but Mildred finds Gayle’s nose to be any kind of problem.)

I approach an interview with documentarian Gayle Kirschenbaum with these things on my mind. Her newest film, the feature-length “Look at Us Now, Mother,” has won multiple awards on the festival circuit and is currently playing in New York, Los Angeles, and Boca Raton (see here for future screenings); it moves on to Kirschenbaum’s native Long Island in time for Mother’s Day. The film examines Gayle’s often-fraught relationship with her mother, Mildred, and her attempts to heal from familial pains of the past. The project evolved from a short documentary of Gayle’s called “My Nose” (2007), in which Mildred tries to convince her daughter that she dearly needs a nose job and Gayle agrees to go with her for consults with a few plastic surgeons—as long as she can film the process. (The conclusion: No one but Mildred finds Gayle’s nose to be any kind of problem.)

“I never bought into my mother’s criticism—of my nose, my hair, my behavior. I didn’t take it personally, but I wanted to know why it happened,” Gayle says by phone from her apartment in New York (with Mildred, who’s in town from Florida for film screenings, by her side). “It didn’t affect my self-esteem, but it affected my feelings about loving and being loved. And I was always looking for answers. I knew I had to forgive her.”

After “My Nose,” “I saw the need to make the feature film,” Gayle says. “I felt I became an ‘accidental therapist’ for the people dealing with their own issues with their parents and families.”

Photo by Gerald Kirschenbaum

“Look at Us Now Mother” is not what most would call an easy ride. There are photos of young Gayle—usually in formal dresses—gazing up at a glamorous mother who doesn’t seem to know she’s there. (“I’d be dressed up in these things,” Gayle recalls now, “and then break out in rashes!”) There is film footage of her trying unsuccessfully to climb onto her mother’s lap. There is a blistering recollection of Mildred’s parental behavior from one of Gayle’s close childhood friends. There is even footage of current-day Gayle working with her mother in family therapy.

But there is also progress; and, yes, some healing. Some of this happened before Gayle officially began filming, in 2011. In 2006, her father died; Gayle and her mother, both wanting to travel and preferring to do so with a companion, became “travel buddies” and realized they were well suited in this way. While seeing the world, they began to get to know each other as adults with complex histories. “As soon as I started reframing how I looked at my mother, things started changing,” Gayle says.

Photo by Tina Buckman

At times during our interview, I am put on speakerphone so Mildred can hear me. When I ask Gayle if she thinks her mother changed during the making of the movie, Mildred is put on the phone directly and gives me her own answer in one word: “No.”

Mildred may not have changed, but some things have. The mother-daughter joint therapy, for instance, was very helpful to Gayle. “One of the things that was insightful [during filming] came from one of the therapists,” Gayle says, “when she pointed out that I was an entirely different person than the rest of my family.” In the film, the therapist notes that practicality and matter-of-factness reigned supreme in the Kirschenbaum home, and no one knew how to handle an emotional little girl who wanted to express big feelings. Indeed, the moment brings some insight and a sense of peace to viewers, too.

Also revealing and even more poignant is a scene in which Mildred gives a tour of her Florida home. The paintings: by Gayle. The sculptures: Gayle’s work. Drawings: Gayle again. “Gayle could do anything,” Mildred says with obvious pride, reflecting on the child with artistic talent who has become a successful adult in the arts. Mildred doesn’t always seem to understand Gayle, but she is proud of her. Perhaps she always was.

As for why she agreed to participate in the film, Mildred (back on speakerphone) tells me something that it’s hard to imagine her having said in Gayle’s youth: “I love her too much to refuse her.”

The film raises as many (difficult) questions as it answers; but it’s compelling from beginning to end. “People say the film changed their lives,” Gayle says, “and put them back in touch with their parents.”

Forgiveness, she continues, is possible as a process even on one’s own: “I made this film to help other people. I tell people, even if the person who hurt you is long gone—you do the work for yourself.”

http://www.lookatusnowmother.com

Please wait...

Please wait...