The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

June 15, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

This Artist Teaches Woman Power

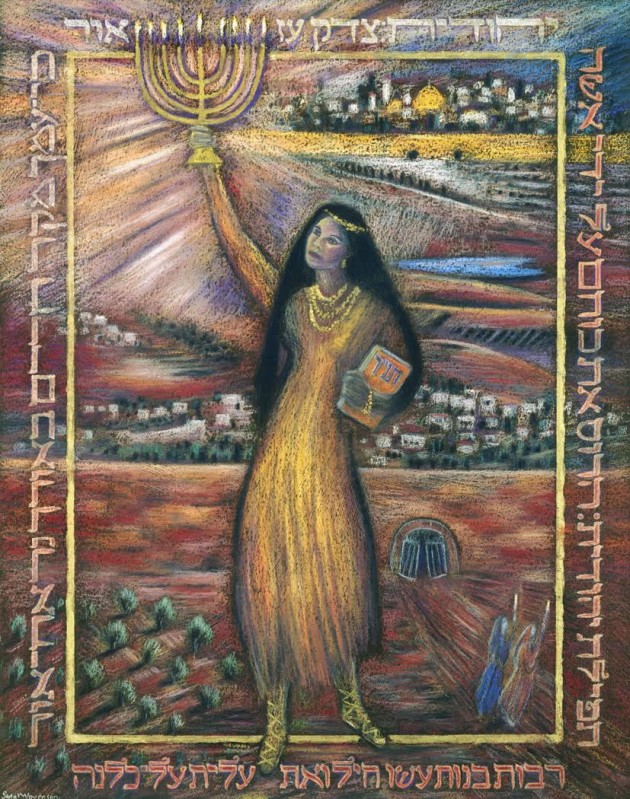

“Evening’s Flight,” Archival Pigment Print. © Sara M Novenson 2012

The first thing you notice when looking at Sara M. Novenson’s paintings are the colors: Rich and vibrant, the blues, pinks, purples, reds and yellows invite you to peer closely, and whether you’re perusing her Great Women of the Bible series or her landscapes, the limited-edition work is striking. What’s more, most of Novenson’s art is bordered by hand-painted Hebrew letters—excerpts from the Psalms as well as blessings—that remind us to appreciate the miracle of creation.

Collectors of Novenson’s work include actor Fran Drescher, the late musician Frank Zappa (1940-1993) and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and she has had exhibitions throughout much of the world. Novenson has also run her own gallery on Santa Fe, New Mexico’s famed Canyon Road since 1996.

A reviewer, writing in the Santa Fe Focus, describes her creations as “dazzling,” with “life-inspiring rays of sun and people shimmering with power and beauty.” But most notable, the reviewer wrote, is “the female energy and spirituality” each painting exudes.

This, Novenson told Lilith, is exactly what she intended. In fact, her Women of the Bible series aims to imbue viewers with a better understanding of female power, and whether they’re seeing images of Deborah, Esther, Hannah, Judith, Leah, Miriam, Naomi, Rachel, Rebecca, Ruth or Sarah, she hopes they’ll walk away feeling “empowered from both within and without.”

Take her painting of Judith. Dressed in gold, Judith is holding a menorah high above her head, a stance indicating her triumph over General Holofernes, the hated military henchman of Assyrian King Nebuchadnezzar. “Judith was the widow of a judge,” Novenson begins. “Shortly after her husband’s death a spy came to the hills where the Jews lived and informed them that they were about to be attacked. Holofernes had already begun withholding water from the community so it was only a matter of time before everyone was going to die of dehydration.”

“Judith” from the Women of the Bible Series and the Book Illuminated Visions, Women of the Bible, Archival Pigment Print. © Sara M Novenson 2012

Judith, Novenson continues, prayed about the situation and then took off her mourner’s black, put on beautiful clothing and jewelry, and went to where Holofernes was staying. He was attracted to her and invited her to a banquet where he proceeded to get really drunk. “He later invited her back to his tent. She went, but when she got there she took a sword from the wall and cut his head off. Without Judith, the Maccabees would not have happened. She helped them see that it was possible to resist tyranny.”

As she tells Judith’s story, Novenson sounds both awestruck and proud. “Judith asked God to work through her and had the courage to take action. She used her mind to figure out what she needed to do. Maybe she was really afraid, but she did it anyway,” she gushes.

Other women in the series are similarly powerful, she says, a dramatic mix of ferocity, fortitude, strength and sass.

“Painting for me is a prayer of gratitude,” Novenson explains, and regardless of subject – whether she is depicting people or the world’s natural beauty – she says that her efforts bring her face-to-face with “the presence of God.” Particularly important, she says, is the light and color of New Mexico’s topography.

“Blessing of the Sun, Violet,” Archival Pigment Print. © Sara M Novenson 2012

A transplant – Novenson grew up in Teaneck, New Jersey and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York City – she fell in love with the US west as a five-year-old, when her family took a cross-country car trip to California that included a stopover somewhere in New Mexico. “Even as a kid, I knew I did not belong in New York City,” she laughs.

She also knew that she had to make art. Her dad was an amateur photographer and before she was eight, she’d learned to develop film in his darkroom. By 12, she was taking the bus into Manhattan for summer classes at the Art Students’ League, but a desire to move west nagged at her. After college, she headed to Albuquerque. “I was painting a lot there,” she says, “and doing graphic design, making jewelry and waiting tables to get by, but I moved back to New York in 1980 because I felt that there were not enough art opportunities for me in New Mexico. Nonetheless, I promised myself that after a few years, I’d move back.”

In 1984, however, Novenson married a musician; when he got a job with the Radio and TV Orchestra of Cologne, Germany, the pair moved abroad. Although Novenson had been reared in a religiously observant family, it was only after she got to Germany that the need to make explicitly Jewish art became apparent to her. “It was weird,” she explains. “I’d walk into a restaurant for dinner and get these awful feelings. I’d later learn that the site had once been in the heart of the Jewish community.” She was also shocked, she says, to discover that many European Jews still kept silent about their heritage.

“Isaac Bashevis Singer became my favorite writer when I was living in Germany,” she says. “I Ioved his stories. They were visceral, as if the words formed paintings that I could actually see. One night, my husband was on the road and I was reading “Satan in Goray,” a story about one of the pogroms of the 1600s. It was very descriptive, very scary to me. I decided I had to stop reading and turned on the TV. And there he was: Isaac Bashevis Singer was being interviewed. I’d recently read his short story “There Are No Coincidences,” so I was absolutely stunned by the synchronicity. It inspired me to begin studying Jewish folk art and learn about all the work that had been wiped out by the Holocaust. At that point I also started visiting every Jewish museum I could get to in Europe.”

Novenson eventually left her spouse, returned to New York, and, in 1992, kept her promise to herself by moving to Santa Fe. She has since immersed herself in study of Torah, Midrash and Kabbalah, an effort that has been incorporated into her paintings, illustrations and drawings. Art, she says, is her way of honoring the struggles and triumphs of her fore-parents. But she does more than this. Her lectures about Jewish art, folk traditions and Biblical heroines have taken her to every corner of the US – including churches and other non-Jewish venues.

It’s clear that Novenson, now 61, loves juggling scholarship with creativity.

She is currently at work on a 13th portrait in the Women of the Bible series and frequently travels to the Chama River to paint the birds, flora and fauna that live and grow there. As she breathes in the landscape, she says that one particular Psalm resonates most loudly: “With You is the source of life. By the light may we see light.”

And we do.

Please wait...

Please wait...