The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

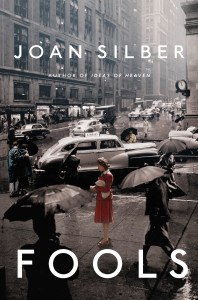

January 23, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Who are the fools here?

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

YZM: Let’s talk about the concept of linked stories. What does this form allow that others don’t? How does such a book differ from a novel or a more conventional story collection?

JS: This is the third book of linked stories I’ve done. There are lots of things I love about the form. It lets me treat material from different angles–a minor character in one is major in another—and I can work different sides of a theme. In this book, for instance, we see the dilemmas in being a fool for an idea, and the disadvantages in not being one.

Linked stories used to be considered an apprentice form, written by writers who really wanted to do novels. (Not true for me–I’d done three novels first.) Now it has its own popularity—there are definitely more linked collections around.

One of my favorite things about the form is that characters who are dislikeable in one story can be humans we’re allied with in another. (Liliane, for example.) There’s a beautiful quote from John Berger in which he says, “Never again shall a single story be told as if it were the only one.”

YZM: The title of the book is taken from the first story, Fools. Who are the fools here and why?

JS: The fools in the first story are anarchists in the 1920s, who are considered foolish for their dedication to an impractical idea. Vera, the main character, is actually quite sensible by nature, and she has to make her own peace with compromise and with conflicts between principle and desire. Other characters are distinctly not idealistic—Anthony, in “The Hanging Fruit,” is a thief and a drunk, and Louise in “Two Opinions” tries to stay out of the fray. But, as Louise’s mother points out, they all have to choose in some way.

YZM: So many of your characters are searching for some kind of meaning in either religion or politics. The Jewish characters don’t seem to find what they need in their faith; how and why has it failed them?

JS: That’s a good question. It’s true that I don’t have characters who find what they need in Judaism. I myself don’t believe in a personal God, but I have characters who do plenty of things I wouldn’t do. In Fools, the two characters who are Jewish by birth—Gerard, who’s untrained in Judaism, and Adinah, who’s very trained—both have a need to re-invent themselves.

YZM: The character of Adinah is especially interesting—an Orthodox girl who becomes a Muslim. Can you talk about the inspiration for her? Is she a fool too?

JS: Adinah is based on a memory of someone I met briefly in my twenties—I don’t really remember if Sufism was her new direction or another belief system. I do recall a friend reporting her pregnancy and saying, “She looks like a deer.” I pretty much made up the rest. I’m always interested in people who make radical changes in their lives. An earlier book was called In My Other Life. I see Adinah as someone whose nature doesn’t change that much—for all her mildness, she has a real capacity for intense ardor and devotion, and it finds a new and surprising channel. These surprises are, of course, what fiction likes.

YZM: You have written both collections of stories and novels; are you partial to one form over the other and if so, why?

JS: I feel that I’ve done my best work in the linked story form. So far. In fact, I’m now working on a novel—I didn’t want to write a fourth book that was too similar to the last three, and I was happy to find myself with characters whose circumstances lent themselves to this shape. I have it planned out in a very sketchy way—at this point, I have some faith in my ability to invent as I go along.

YZM: You teach writing at Sarah Lawrence College; how does teaching inform your own practice of the craft?

JS: I always tell my students to do as I say, not as I do (for instance, I make them write summaries if they’re working on novels). In the many years I’ve been teaching, my own ideas about writing have changed and developed, and having to articulate them to students has helped this development. I have wonderful students who ask great, pesky questions.

Please wait...

Please wait...