The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

September 10, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

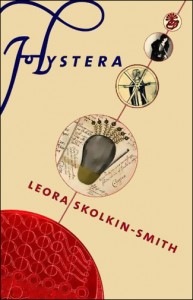

Hystera

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: This is an unflinching portrait of mental illness; what drew you to the subject?

Leora Skolkin Smith: I was drawn to writing about mental illness by the popular medical and cultural presentations of it. I felt that the continual oversimplifications in the media threw more darkness than light onto this disturbing and beguiling state of human behavior and ultimately silenced the cries from those in the throes of it. In recent years, the use of drugs such Prozac have been described in memoirs and accounts of depression but I felt this was only a partial, inadequate answer. I wanted a deeper exploration, one that was not based on easy resolution or being “fixed,” but instead engages philosophical and sexual questions of existence itself, as well as questions about identity and intimacy that transcend our purely medical and limited understanding. I wanted to show that mental illness is part of a continuum of human experience throughout history.YZM: Someone in the novel tells Lilly she looks like Patty Hearst; did you mean to suggest that she is a “prisoner” of her disease?

LSS: Patty Hearst was a symbol first of the sexual identity confusion of the times, then the turbulent economic and class upheaval our society was undergoing in the early 1970s. She had transformed from the well-behaved daughter of a multimillionaire into a wild-haired radical dressed as a guerrilla soldier, holding up banks with a machine gun and shouting slogans about equality out for the poor. The labile nature of identity itself was shown through her transformations. But yes, she was also a prisoner to her own sickness in a sense, her masochistic sexuality, as she had fallen in love with her kidnapper.

YZM: Lilly believes she is growing a “bulb” from between her legs; do you view this in Freudian terms?

LSS: I meant the “bulb” to express the ineffability and mysteriousness of her illness and mental illness in general. I wanted to create the sense of enigma that felt truer to me than the rational truism we apply to illness. It still somehow belonged to the poets to express and had no readymade answers. Though the pharmaceutical revolution has changed everything in many positive ways, I still like to believe there are questions about the nature of identity and existence that remain ineffable. I never thought of the bulb in purely Freudian terms. It came from old prints from the Renaissance and the Middle Ages that depicted personal, unexplainable “spiritual journeys of the soul,” so to speak.

YZM: What roles do the men in Lilly’s life play?

LSS: Lilly, is very much a daughter of her era (She comes of age in the1970s). She sees men as entitled, especially in receiving unconditional nurturing and sustenance from the women around them, as women remain hungry and deprived of such support. When Lilly enters the monastery, she asks why Jesus is on the lap of Mary while she herself feels so abandoned and left out, as if her need for the same for the same nurturance were in fact invisible and illicit. She sees her mother as suffering from that unfed hunger, an unstable self. Her relationship to the mother who abused her is altered by her realization that her father’s demands were insatiable, and drained the possibility of independent existence away from him. Her mother must remain his caretaker, and Lilly was partly responsible for the prison her mother finds herself in after her father becomes brain-damaged, dependent and helpless as a child. This I think is the abuse Lilly feels from men, being rendered invisible in terms of her own neediness, her own helplessness, having to serve only their often unreasonable hungers while starving herself, dwindling away. She is sucked dry by obligation to the men she must take care of, their unquestioned demands on her life and energies. Dr. Burkert is of course, very different just by virtue of his role as physician. He challenges her despairing view that all men are like her father, unable to offer her caring in return. Also her sexual attraction to him further helps her reintegrate a damaged and very undifferentiated sexual identity that had thrown her into psychotic fears and paralysis. He is a catalyst for a change in Lilly if she can accept his help.

YZM: You write with tenderness and familiarity about British-occupied Palestine; can you elaborate on what this means for you?

LSS: I think all my work as a novelist carries this sadness and tenderness for the lost world of an earlier Palestine/Israel. My mother was born in the old city of Jerusalem as was my grandmother and my great grandmother, Some of my maternal family members go back as far as the 1600’s in Jerusalem. My grandfather was in business with his Arab colleagues in Jordan and my uncles attended the University of Beirut. As a child, I spent much time in my mother’s country, cloaked in intoxicatingly beautiful, often mystical stories of lives spent amidst these earlier limestone streets and pine trees, and as Jews, of lives spent and shared with a multicultural neighborhood of Muslims, Christians, and Armenians. The hate and bitterness of war between the Arabs and Jews had not yet poisoned the air because in British Palestine, the streets were not yet divided, and there was a sense of things all around the Biblical places which made the whole earth feel magical to me as a child. Jerusalem was also a very sensual place, full of exotic scents and tastes, stories and ancients spirits I never knew in my Westchester home. I loved it there as a child, before 1967 when the war seemed to change everything.

YZM: Lilly finds solace in the Hebrew texts her mother, a bookbinder, repairs and restores. Can you say more about the meaning these books have for her?

LSS: The symbols Lilly finds in these books bring her back to a sweeter, relationship with her mother, one that isn’t damaged and one she can rely on to bring her meaning and identity. She, like her mother, can lose herself in an imaginative rendering of her world. Her mother taught her the power of finding such quiet self -fulfillment and self-definition through solitude, pursuing an art, a craft. It was a chance to reintegrate the chaos of selfhood, make confusion cohere. But those ancient enduring Hebraic symbols bring Lilly back to that Jerusalem of her childhood, to a universal belonging to worlds larger than herself. And finding those symbols puts Lilly back on a trail home.

Please wait...

Please wait...