The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

August 29, 2013 by Sarah M. Seltzer

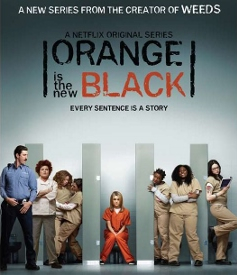

Orange is Our New Obsession

Summer 2013: the season that those of us blessed with Netflix accounts compulsively binge-watched the women’s prison dramedy, “Orange is the New Black.” The series follows a WASPy Smithie named Piper Chapman (the fictional avatar of memoirist Piper Kerman) during her year in the Fed for a youthful indiscretion: acting as a drug mule for her ex-girlfriend. In each episode, viewers not only encounter the sexually flexible love triangles, beefs, and tribulations of the inmates, but also heartbreaking flashbacks that show how they ended up behind bars.

Summer 2013: the season that those of us blessed with Netflix accounts compulsively binge-watched the women’s prison dramedy, “Orange is the New Black.” The series follows a WASPy Smithie named Piper Chapman (the fictional avatar of memoirist Piper Kerman) during her year in the Fed for a youthful indiscretion: acting as a drug mule for her ex-girlfriend. In each episode, viewers not only encounter the sexually flexible love triangles, beefs, and tribulations of the inmates, but also heartbreaking flashbacks that show how they ended up behind bars.

My experience as a viewer was typically intense. I suffered acute insomnia from hours of overstimulation as my husband and I raced towards the final episode. I lay in bed pondering the characters’ fates (“They’re not real!” I reminded myself). I openly sobbed on my couch as the plotlines deepened, exploding the broader caricatures we had initially seen. One supposedly brash inmate, Taystee, returns to prison after struggling on the outside; another stoic inmate, Ms. Claudette, who had finally learned to hope for release, loses that hope. And the kicker: the unstable but observant Suzanne, who’s called “Crazy Eyes” by the other inmates, poignantly asks Piper to explain why they call her that–indicting the audience for laughing at her in earlier episodes.

After I finished watching the show, my obsessing continued. I followed the debate about the show’s accuracy, its race and gender politics, including its groundbreaking transgender character, Sophia, played by Laverne Cox, a transgender actress. Is it okay to use a morally ambiguous white protagonist as a “Trojan Horse” to illuminate the lives of women of color–as the show’s creator Jenji Kohan asserted she did on NPR’s Fresh Air? (Kohan, who’s Jewish, also noted in the interview, with some glee, that Piper Chapman is a “WASPy, cold shiksa.)

And as Roxane Gay asks, is the show’s glowing reception really earned, or are we so starved for decent content about diverse women, that any such show with reasonable smarts seems more revelatory than it actually is (I call this the “Juno Effect”)?

And all that of course, begs the bigger question of whether art, particularly when it depicts an environment that carries a great social weight –like prison–has an obligation. Should artists be responsible for informing the public accurately? or agitating for change? or even telling a representative story?

I’m still mulling a lot of this. But regardless of whether a show with bourgeois/hipster cred should be a catalyst for change in a perfect world, the attention it’s garnering presents a more pragmatic concern: can a show actually alter the way we look at crime and punishment? OITNB’s clear condemnation of such aspects of prison culture as solitary confinement (shown, correctly, as akin to torture) and the power guards have over prisoners is already having an effect on viewers: a colleague dishing on the show over lunch told me, “I love it, but it can be frustrating to watch because I just get madder and madder about the system.”

She was speaking of the prison system–itself an acute symptom of the racist, broken justice system. Interestingly, the show comes at a cultural moment when reform, in the tiniest of increments, feels possible. NYC’s discriminatory Stop and Frisk program has been overruled and challenged. Federal minimum sentencing for drug crimes has been halted by Attorney General Holder–mostly symbolic, but not insignificant. Now there remains a mountain of other goals to achieve: curbing solitary confinement, ending the shackling of pregnant inmates, curtailing the ability of guards to harass and retaliate against inmates and overarching all that, stopping incarceration for minor drug offenses. And then we and must can get down to figuring out what justice really ought to look like.

As OITNB acknowledges, progress in prison reform has been difficult because average American taxpayers aren’t overly concerned with the rights of felons, at least not in the abstract. But that state of indifference can be appealed to, perhaps–and maybe art is a good medium for a heart-changing effort. OITNB, after all, succeeds to the extent it does at showing how dehumanizing prison is because it acknowledges the humanity of those behind the prison walls.

Please wait...

Please wait...