by admin

A Child’s Perspective on Chile’s Disappeared: “I Lived on Butterfly Hill,” by Marjorie Agosin

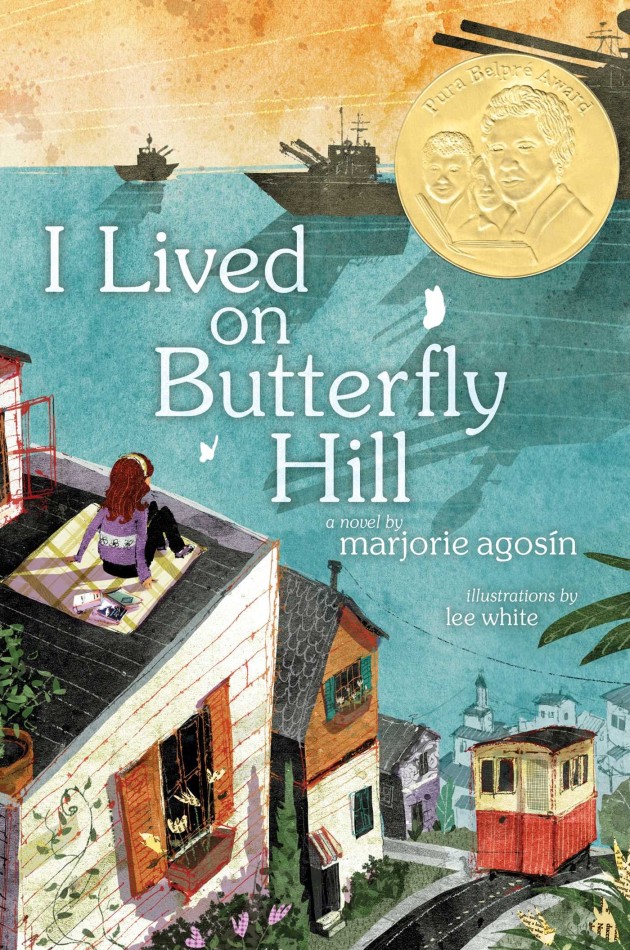

I Lived on Butterfly Hill, by Marjorie Agosin, opens in the idyllic coastal town of Valparaiso, Chile, in the early 1970s. This middle-grade historical novel, translated from the Spanish by E.M. O’Connor with illustrations by Lee White (Atheneum, $17.99), is based loosely on the 1973 coup by General Augusto Pinochet, who ousted socialist president Salvador Allende and ruled Chile as a military dictator for 17 years.

I Lived on Butterfly Hill, by Marjorie Agosin, opens in the idyllic coastal town of Valparaiso, Chile, in the early 1970s. This middle-grade historical novel, translated from the Spanish by E.M. O’Connor with illustrations by Lee White (Atheneum, $17.99), is based loosely on the 1973 coup by General Augusto Pinochet, who ousted socialist president Salvador Allende and ruled Chile as a military dictator for 17 years.

Agosin — known for her many adult books set in Chile — does not mention these historical figures by name, and here the rule of terror lasts only a couple

of years.

The narrator of this beautiful, long (450-page) book is 11-year-old Celeste Marconi, whose voice, in the beginning, is full of optimism and wonder, her life replete with beloved school chums, a little harmless folk magic, favorite foods and family rituals. Her mother and father, both physicians, devote themselves to helping poor families. Slowly cloud storms gather, beginning with the increasing presence of warships in the harbor, and Celeste has a growing sense that something is wrong. At first none of the grownups will confirm her worries, but as all kinds of new rules are imposed, people she knows — including some of her classmates — disappear. Threats are made, and soon her activist parents must go into hiding, leaving her in the care of her grandmother, Abuela Frida, who escaped the Holocaust and knows about hard times, and their housekeeper, Nana Delfina, who helped raise Celeste’s mother. The older women come to realize that for her own safety they must send Celeste away, too.

Sent to live with her aunt in Maine, Celeste is suddenly a misunderstood and unwelcome stranger, who slowly makes friends with other marginalized immigrant children, and is encouraged by the attention of a few kind teachers while all the while missing home.

This unusual book explores political terror and fear from the point of view of a pre-adolescent girl who’s able to develop the resilience required of a survivor. An important lesson here for young readers accustomed, perhaps, to books about slavery or about the Holocaust, is that very bad things can happen all over the world, and that some of one’s own classmates may have endured experiences unlike those of most children their age. Though things are never quite the same, Celeste and her family are eventually reunited, and along with her survivor grandmother, who had collected and hid forbidden books during the years of the dictatorship, Celeste helps establish a library to encourage literacy.

Agosin, who teaches Spanish at Wellesley, is a human rights activist in addition to being a prolific author; she left Chile for the United States with her parents as an adolescent in the 1970s.