by admin

BLT Judaism

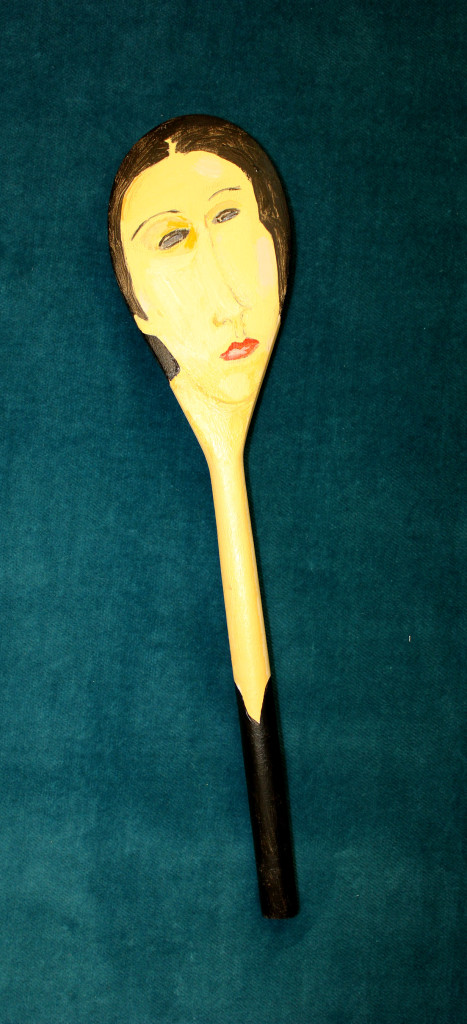

“Mo-diggin-liani,” by Rhea Dennis.

My grandfather, a Holocaust survivor, used to tell the story of the family’s escape from Europe — a harrowing narrative that included bombings and imprisonment and hunger and frostbite, near-misses and unexpected escapes. One small piece of that story concerned the family’s passage across Siberia by train in 1940. As the train rumbled slowly across the Russian landscape, my grandparents got hold of some food, including a large and apparently very tasty pork sausage.

Whatever my family’s privations on that train ride, at that point in their journey they were not going so hungry that eating that sausage was a matter of life or death. They ate it anyway and proclaimed it delicious. My Orthodox great-grandfather, a tolerant soul, sat in another car and graciously pretended not to know.

That story has always stuck in my head. And in the way of childhood stories, it’s become part of my map of the world.

My mother, whose family was dispersed by the war and later settled mainly in Israel, wanted her children to grow up speaking Hebrew. My father, who grew up working alongside his father in a sweeping-compound factory in Newark and whose Jewish education was far more basic and low-key, was skeptical about religious education for his children but agreed to it nonetheless. So, off to Jewish day school I went, though I always sensed I was there to study language and culture as much as religion.

In school, I was the only kid in my grade whose family admitted to not keeping kosher. And while I was an eager student and liked my classes — and while I was powerfully, indelibly shaped by immersion in currents of language and melody and psalms and argumentation and infinitely layered history — I realized at some point that I saw the stories from the Torah the same way I saw the plays and novels we were reading in English class: All of them were fascinating and instructive, and none of them was word-for-word true.

At some point, too, it occurred to me that the religious people I saw around me, wherever they happened to fit on the spectrum of observance, were all picking and choosing: interpreting laws and verses to fit their world-views and to allow them to sing the songs they wanted to sing, whether these were songs of individualism or community, of pluralism or of tribalism, of freedom or of obedience. Even the strictest among the Orthodox seemed to be picking and choosing, interpreting the law in order to best sing their song, which seemed to me to be a song of safety-through-diligence: The more diligent you were about an infinite proliferation of laws, the more God approved of you, and the safer and more blessed you were in this world.

But it seemed patent to me that God, if there was a God, didn’t much care which song one sang, so long as it was sung in good faith. The same train engine that pulled my Orthodox great-grandfather across Siberia and out of harm’s way also pulled my sausage-eating grandparents, and at the exact same speed. And I could never wrap my mind around the notion that some heavenly train would eventually decouple and proceed to carry them on different tracks because of their eating habits. Religious practice, as far as I could see, was all a work of art: beautiful, useful wherever it helped us do good, and nothing if not creative.

For a long time, though, I didn’t eat pork. I figured, somehow, that since I didn’t observe kashrut in the larger sense, this was the least I could do. I recall explaining this once to a non-Jewish friend: My grandparents had their world shattered and were nearly killed because of who they were; the least I could do was keep one symbolic custom and not eat pork.

But I soon came to feel that this was the wrong reasoning. It’s one thing to keep kosher because you believe it’s the right thing to do. But abstaining simply because of Hitler, on the other hand, felt like the wrong motivation. Eventually I came to see my grandparents’ sausage-eating story as a story of healthy defiance. Hitler wasn’t going to tell them who to be or what to eat, and neither was Jewish law. Keeping faith in their identity, despite the ripping apart of their world, meant sticking with who they actually were: intellectuals with senses of humor; patriotic Poles who were also Zionists; proud and devoted Jews who liked an occasional pork sausage. If I were going to shape any notion of kashrut in their honor, it would be a bit absurd to honor a fictitious version of them rather than who they actually were.

As an adult, I’ve evolved a rather unusual relationship with kashrut. I keep strictly to the Yom Kippur fast; for some reason I don’t fully understand, I’m keenly observant about food during Passover; we keep a kosher-style kitchen, and I generally go with my husband’s level of observance where it’s stricter than mine. But I don’t actually believe in keeping kosher. I don’t feel sheepish about it, either — because, though my childhood teachers would disagree, I don’t think that morality is necessarily on the side of the more observant and the rest of us are just failing to live up to it. I have my own principled reasons for not keeping kosher. Among them: I have too many dear non-Jewish friends to feel comfortable with the exclusion that often goes with kashrut. Kashrut too readily becomes a dividing line between who is “in” and who is “out” of a community — a permission slip to violate basic neighborly openness. If our most basic form of human generosity is food, then I never want the message I send to friends and neighbors to be a demeaning your food isn’t good enough for our table.

At the same time, I’m a product of nine years of Jewish day school, and this means an awareness of the taboos around food is ingrained in me. I will never be able to eat a BLT without being aware of breaking a taboo.

This, of course, makes BLTs delicious. And since we all need breakable taboos in life, the BLT has over the years become my pressure-valve of choice. When I am having a truly lousy day — when something is driving me so profoundly nuts that I want to catch a shuttle to Jupiter; when I want to quit every responsibility I have, but of course I can’t — the BLT is waiting for me in that little psychic box marked in case of emergency, break glass.

I ration my BLTs. I eat one maybe once a year, sometimes only once every two years. What’s more, I calibrate my position on the BLT scale with grim glee. I will text my friend Tova: ice dam w roof leak, kids home sick, am at BLT DEFCON 2. The BLT scale has become a way to register protest and at the same time soldier on. It’s for those moments when I’ve had it with suffering the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune and would dearly love to take up some goddamn arms for once against a sea of troubles — but am forced to acknowledge that it’s a lot less messy and a lot less damaging to just take myself out for a sandwich.

My own children attend Jewish day school now. I send them there so they can learn Hebrew and Jewish text and literature — and so that, should they choose to do so, they’ll have the tools to sing their own songs in a Jewish key. And if it happens to be my personal preference that they go on to use this knowledge to lead somewhat heretical lives, then what of it? That choice isn’t up to me, and I know it, and that’s fine. Religious faith offers a comfort I’ve often wished I had — and just because I’ve never found a navigable path to belief doesn’t mean my kids shouldn’t be able to. Some of my favorite people are religious, and if my kids end up religious, I’ll still love them just as much. Even if it means one day I need to buy a new set of dishes.

It may be that in sending my children to a Jewish day school while practicing my own form of sometimes-attitudinal Judaism, I’m teaching hypocrisy. But I don’t think so — that is, not unless you count every single picker-and-chooser in the tribe as a hypocrite. I think I’m encouraging my kids to recognize both the riches and the freedom available to them in ritual, to size up the principle of a thing, and chart their own course within the system — or outside of it. Whether that course leads to pork sausages or observance of kashrut will be up to them.

For now, my kids know I sometimes eat treyf — but not, I think, that I davka eat treyf. Nor that the BLT has somehow evolved, without my intending it, into a ritual food.

But when the day inevitably comes when they overhear me discussing my DEFCON status, I hope to pass along a family legacy: Choose your own devotions, whatever they are. Break the rules consciously, break the rules because you believe in breaking them, break the rules and hold your head high. And then sing your heart out.

Rachel Kadish is the author of the novels From a Sealed Room and Tolstoy Lied: a Love Story, as well as the forthcoming novella I Was Here.

This article is reprinted from Tablet Magazine, the online magazine of Jewish news, ideas, and culture, at tabletmag.com.