by Michelle Brafman

Dr. Norman Vincent Peale and Me

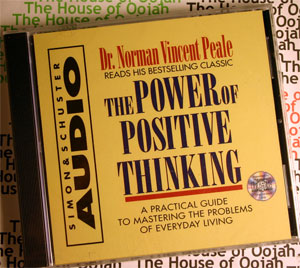

It began with a glance. I was walking out of Barnes & Noble on a warm May afternoon when I spotted him, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, or, shall I say, his four-disc audio book, The Power of Positive Thinking, perched on the “bargain buys” table in the foyer. At that time, I was unaware that Dr. Norman Vincent Peale had been an evangelist and close friend to Richard Nixon and Billy Graham and enemy of my hero, John F. Kennedy. I didn’t know he’d coined the expression “When life hands you lemons, make lemonade.” I only knew that I’d been feeling a bit blue lately, and who couldn’t benefit from some positive thinking? I paid for the boxed set with the last 15 dollars in my wallet.

Five minutes into the first disc, and he had me. I credit his preacher’s meter, the way he punched the hell out of his iambs, his words bypassing my frontal lobe, whispering to my lower brain stem, and then traveling deeper, deeper down to my soul.

I was thankful that there wasn’t a photo of Dr. Peale on the CD cover. I liked him faceless. Although, if pressed, I’d say that I imagined him looking a bit like my late step-grandfather, Dave Bloom, in a crisp white short-sleeved dress shirt with a plastic pen protector in his breast pocket and black rimmed Poindexter glasses with attachable shades.

It only took me eight trips to the carpool line to finish the boxed set. Each disc had a new lesson for me. If I listened to Dr. Peale, I could break my worry habit, get other people to like me, believe in myself, and develop the power to reach my goals. My kids weren’t thrilled about our listening choice, but they were still young and malleable enough to endure Dr. Peale–or at least block him out while they buried their heads in Harry Potter and Captain Underpants.

Dr. Peale convinced me that I could banish my demons by “driving prayer” into my thoughts of inferiority. It was simple. I just had to practice the following affirmation 10 times a day: “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me.” (Philippians 4:13) So I did, despite the fact that I am not only a Jew, but was raised in an Orthodox community.

Instead of protesting Vietnam or doing the Ice Storm thing, my parents fell under the spell of a charismatic Chasidic rabbi who played the guitar and listened while his congregants unloaded their dreams and failures. I mean really listened, Bill Clinton-style, like they were the most important people in the congregation. My parents opened their Milwaukee home to their East Side, secular Jewish friends to hear the rabbi and his wife explain the Torah’s 613 commandments. My father became captivated by the intellectual rigor of parsing the words of the text and applying the lessons of our forefathers’ conundrums and choices to contemporary moral dilemmas. On Saturday mornings, we would drive to the rabbi’s synagogue on the West Side, back to the streets where my father had played kick-the-can, passing the duplex where his father had died, and the working-class neighborhood he’d left behind.

The rabbi’s daughters would whisk me off to a small chapel, adjacent to the mauve tiled bathroom that smelled like a urinal cake. They’d school me on all the things that “You’re not allowed” or “naallowed” to do on Shabbos. You’re naallowed to rip toilet paper, write, turn on a light, turn on the oven. The Sabbath is a day of rest, and since these tasks require work, they are deemed muksah, forbidden. One of the younger daughters would narrow her otherwise warm brown eyes, “You’re naallowed to drive a car.” My cheeks would grew hot (we’d park a mile from the synagogue and hike in).

At the end of the service, the rabbi would call the children up to the altar, and blanket our heads with his musty prayer shawl. Our aromas mingled−little boy sweat and the sweet smell of milk encrusted on our lips from our morning cereal. There was no talk of muksah under this tent. We were children and we were perfect in the here and now. My heart beat quickly as I listened to him, a faceless voice speaking to the Almighty on our behalf.

Dr. Peale never once uttered the word muksah. He was all about helping me reach my potential and believe in God! He told me that I could reclaim my power by stating, “the kingdom of God is within me” (Luke 17:21).

Full disclosure. This wasn’t the first time I’d been seduced by such teachings. In college, I sang in a gospel choir, barely able to hide my jealousy as my choir-mates belted out lyrics about how they could depend on God “because He could do wondrous things, now can’t you see.” I couldn’t see anything. And who was He?

I had God envy, and I had it bad. I had it so badly that a few years later I dated a born-again Christian. The metal fish on his rear bumper, our late night bull sessions about my inability to accept Jesus Christ as my personal savior, and the way he alternated between deeming me a chosen person and a Jesus-killer creeped me out a bit, but I can’t say that I was turned off by his faith.

To hear me talk you’d think that I had no religion in my life. Not true. My husband and I have scrimped to send our kids to a Jewish day school. We attend services regularly enough for the clergy to know our names, and for years we belonged to a lay-lead Torah study group where we met monthly to unpack the sacred text. When I brought my father to a session with our smart friends, he slipped easily into our critical analysis of the designated parsha and accompanying commentary. We’d been meeting for a few years when one of our monthly leaders asked us to talk about our belief in God. Awkward silence as my kids would say. I too fidgeted and cleared my throat as if someone had just asked me to reveal my true weight (in contrast to the number that appears on my driver’s license) or take a peek at the slender space behind my couch and the wall, where dust bunnies, pen caps, and Lord knows what else reside. How could I tell my friends that listening to Dr. Peale offered me a Batline to God? Or that I heeded Dr. Peale’s advice to “Ten times a day repeat these dynamic words, “If God be for us, who can be against us?” (Romans 8:31) (Stop reading and repeat them NOW slowly and confidently.)”

I don’t remember how I answered the question, or how my infatuation with Dr. Norman Vincent Peale ended, or when exactly I realized that I didn’t need Dr. Peale or any rabbi to speak to God on my behalf. I could do it for myself.

I’d always turn to God during moments of fear and uncertainty. My husband and I had recited a prayer from Rabbi Nina Beth Cardin’s Tears of Sorrow, Seeds of Hope every night of my pregnancies, and I pray while I’m waiting for the results of any medical test. I both pray and ask for forgiveness during our chazzan’s grab-your-soul- by-the collar recitation of the Ashamnu every Yom Kippur. As a former Jewish day school student, I’ve also recited my share of daily prayers, yet they felt more like a mere ritual than a spiritual practice. Dr. Norman Vincent Peale helped me combine the two, and I have since replaced the scripture with my own prayers, most taken from Jewish liturgy.

Praying reminds my micro-managing self that there is a limit to what I can control in my world, and that God’s timeline doesn’t always mesh with mine. For starters, I pray for the impulse control to refrain from gossiping and bragging, and I pray for the courage to risk failing miserably and the humility to admit when I’ve climbed onto my high horse. I pray for the attentiveness to listen to my family members complete their sentences without checking my iPhone or finishing their thoughts. I pray for the well being of my loved ones and for people who tick me off beyond belief; sometimes they’re the same person. I pray for the grace to stop wallowing about life not affording me enough of the good stuff and the gratitude to say thank you for our health and the financial security to enjoy an occasional sushi dinner and movie with my husband. I pray for the mothers of the children who were killed in Aurora and Newtown and the ones who survived, and I pray for gun control legislation that will protect us all.

I pray for coincidences like my chance encounter with Dr. Norman Vincent Peale at the Barnes & Noble and the quiet to recognize them as such. Dr. Peale and I are not together anymore, but every once in a while I’ll dust off my boxed set and wait until I’m driving alone to pop disc 3 into my CD player. I’ll thank him quietly for shining a light on a path toward a place of surrender and gratitude. What an unlikely messenger. Kind of makes me believe in God.

Michelle Brafman has received numerous awards for her fiction, including a Special Mention in the 2010 Pushcart Prize Anthology and first prize in the the Lilith Magazine Fiction Contest Her work has appeared in Slate, Tablet, the minnesota review, Blackbird, and elsewhere. She teaches fiction writing at the Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing Program and George Washington University.www.michellebrafman.com