by admin

All That Remains of Etta

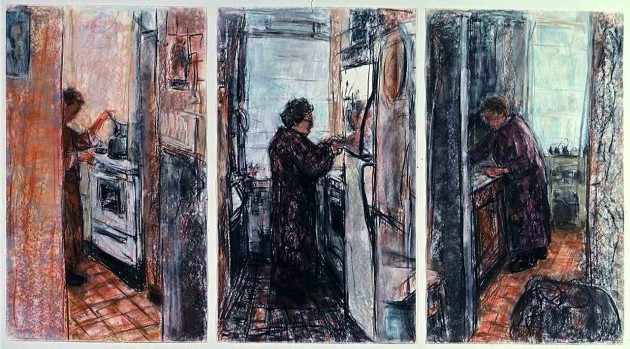

The saving grace about her mother’s house, when Joan had dismantled it last spring with all the birds returning to the greenway, was finding her mother’s hand in everything. Little notes, like the one on the newspaper clipping, found in the top drawer of her desk, Simon Wiesenthal was a good man. Or the slip of paper, yellowed and torn at the edge, an address for somewhere in Poland, where your grandfather was born. Joan had found all the notes — to Joan, for Lisa, give to Philip. On the bottom of the silver tea service, which Joan keeps in her living room, the yellow sticky read: For Joan. You should know Aunt Edith sewed these into the lining of her coat and walked across Europe to escape. Keep, please, to which Joan had added her own note: For Lisa when I’m gone. But there is nothing from Etta. No notes. No last words. No directions of who should get what. Just a cracked teacup she was holding when her heart gave, a closet of tracksuits and housecoats and boxes of things stored in her basement. Even Etta’s old cameras and her black and white photos, wrapped three times in bubble wrap, were left to Joan’s discretion.

The saving grace about her mother’s house, when Joan had dismantled it last spring with all the birds returning to the greenway, was finding her mother’s hand in everything. Little notes, like the one on the newspaper clipping, found in the top drawer of her desk, Simon Wiesenthal was a good man. Or the slip of paper, yellowed and torn at the edge, an address for somewhere in Poland, where your grandfather was born. Joan had found all the notes — to Joan, for Lisa, give to Philip. On the bottom of the silver tea service, which Joan keeps in her living room, the yellow sticky read: For Joan. You should know Aunt Edith sewed these into the lining of her coat and walked across Europe to escape. Keep, please, to which Joan had added her own note: For Lisa when I’m gone. But there is nothing from Etta. No notes. No last words. No directions of who should get what. Just a cracked teacup she was holding when her heart gave, a closet of tracksuits and housecoats and boxes of things stored in her basement. Even Etta’s old cameras and her black and white photos, wrapped three times in bubble wrap, were left to Joan’s discretion.

Joan tried. She tried to disburse what she could among Edward’s sons and their wives but outside of the new television and a two-year old computer, they wanted nothing. Even the boots in the white and blue Zappos box, never worn and in Merle’s size, had been refused.

“They’re good winter boots. You should take them,” Joan said when Merle stopped by in between dropping her children off at preschool and picking up her mother for brunch.

“Oh, I couldn’t take them,” Merle had said. “I could never wear a dead person’s shoes.”

Joan shoves the last of Etta’s velour tracksuits into the box for Salvation Army. Left to pack: a few things from the kitchen, some of the older linens and towels, a pillow needlepointed decades ago, the oil painting no one wanted. Joan has been at this so long that the discard pile is beginning to look fresh and she catches herself eyeing that needlepoint pillow for her living room. Enough! What she really needs is a good manicure; another two nails broken and the synthetic feel of velour caught in her cuticles. And coffee. She wants coffee. She would dig out the percolator if only she hadn’t thrown out that can of Folgers.

But she is almost finished. She should beat the predicted snowfall home and meet Edward in time for dinner. Tomorrow at this time, the condo will be painted, the carpet washer is scheduled, and the For Sale sign readied. The last remaining remnants of Etta will be whisked away, bits and pieces of her life redistributed to strangers on the shelves of secondhand stores or in eBay auctions.

As she makes a final survey of her sister-in-law’s condo, she feels the chill in the air. The windows have turned to smoked mirror from the darkness outside flecked with bits of frost along the edges. It is cold without the insulation of things.

Joan pulls the tissue from her sleeve and wipes at her nose before switching on the electric space heater. A burning smell closes in around her, mixes with a leftover stench of ginger and brine. Joan can still smell the dog. A mix of wet fur and urine.

It had been Edward’s suggestion to put the dog down. “She’s blind and pees on everything,” he said at breakfast on the day of the funeral.

And so two days after Etta was buried, Joan had carted the dog, the little white shih tzu, to the vet. She sat with the dog in her car for almost an hour. When she finally went into the vet’s office, she signed the forms to have the office dispose of the carcass and then returned to the task of packing up Etta’s things.

“Did I get it right?” Joan says to the empty condo as she reaches for the last roll of packing tape and the scissors with the blue handle. She is startled by a knock at the door and drops the scissors to the floor, just missing her foot.

At the door is an elderly woman. Her face is slightly tanned, and she is wearing a black fur hat with wisps of gray hair curling out from underneath the rolled edge. Her coat is made of thick black wool that is familiar to Joan. My mother’s coat, she thinks. Like a talisman for survivors, Joan remembers that her mother, her aunt, her grandmother, and a neighbor — she actually remembers a neighbor’s coat from when she was small — all wore black wool coats to temple on Saturdays. The woman standing at Etta’s door has petite hands that are gloved in black leather. Dangling from her right hand is a red leather leash.

“I’ve come for Leyke,” she says.

At first Joan thinks this woman is talking about the old camera equipment. Was there a Leica in the box? Did I drop it off for resale? Did someone take the cameras?

But before Joan can answer, the woman says, “I am Mrs. Rutzel. I am here for the dog, Leyke.”

And in that instant, Joan remembers the dog.

The elderly woman standing in front of her has a slight Polish accent, and her voice grazes at Joan’s heart, and with a slight hesitation, Joan cannot help but think she has seen this face in one of Etta’s photographs.

“Please come in,” she asks Mrs. Rutzel.

“No,” Mrs. Rutzel says. “I just need the dog.”

“It’s so cold out here, maybe you should come in.”

“Thank you, no. I should have been to the funeral. I was in Boca and saw the paper, the Jewish News? Even in Florida you can get the Detroit issue! Ach! I am so sorry for Etta, may she rest in peace. She wanted for me Leyke. I tried calling, to make the arrangements, but the phone. It is out of order? So I come. The dog, please.” Her w’s sound like v’s so that everything she says has a hard edge to it, and yes, Joan remembers how quickly everything was turned off, Etta’s phone, her cable, the Internet service. She will wonder later why she knew nothing of this Mrs. Rutzel, never heard her name, never knew Etta had a friend, a visitor! Joan will remember later having seen unaccounted-for and unexplained waxed bags of cookies from a bakery in Oak Park, and she will think about all of the things overlooked and not known.

“We put the dog to sleep,” she tells Mrs. Rutzel.

“To sleep?” says Mrs. Rutzel. “To sleep?”

“No one wanted to care for the dog; she was old. So we put her down. The vet, we had her put down?”

“She’s dead? The dog? Nebekh, the dog, she is killed? You killed little Leyke?”

“We put her down.”

“Down? Killed? She is gone?” Mrs. Rutzel’s bewilderment is contagious, and Joan finds herself disbelieving the dog is actually gone: Perhaps the vet hadn’t gotten around to it yet; perhaps it didn’t take.

“They do that with gas?” Mrs. Rutzel asks.

The wind has begun to stir around the two women, one standing on the inside of an open door, the other on the outside. Vit gas? she asked. Joan is mesmerized by the start of a light snow, so early, and thinks about the killing. The dog.

“No. No. They do it by injection. Not gassed, the dog wasn’t gassed. She was put down. Humanely,” says Joan, thinking of the blue streak of numbers that ran across her mother’s arm, visible only in summer when she slept in a white linen slip, and thinking that a similar row of numbers must exist on Mrs. Rutzel’s arm as well.

“I am so sorry. I didn’t know. No one said anything to me about you.” Joan picks at her cuticles, drawing a drop of bright blood just at the edge of her middle finger.

“Gvalt! To kill a dog? Why? Mrs. Rutzel’s gloved hand, the one that does not hold the red leather leash, rises to her face. She holds her reddening cheek in her hand.

“If I had known…please come in, it’s so cold,” Joan says, opening the door wide, gesturing to Mrs. Rutzel to step over the threshold. Coffee, Joan suddenly thinks again. If there were coffee, something to eat, she would come inside, they’d straighten this out — what’s to straighten? The dog is gone.

Mrs. Rutzel shakes her head, and the leash dangles in the quiet of snow falling, bells for the dead.

“Mrs. Rutzel, please,” says Joan. “It was a mistake.” It was all a mistake. Standing in the white cold, a leash dangling, Joan struggles to remember some conversation, any conversation, she had with Etta in which she asked more than Do you need paper towels?

“Oy! What a mistake!”

Joan whispers again, “It was a mistake.”

Mrs. Rutzel, her hand still on her cheek, her head turning slightly from side to side, says only, “That Leyke, you know, she loved the cookies from the Polish bakery. Ach! Nebekh. Poor hintele.”

Swirling skies of white snow grow heavier around the two women, and Joan’s vision is blurred by the thick downfall. Cookies for a dog, and Joan remembers her mother handing her a cookie meant for a dog but eaten instead by five-year-old Joan. She thinks about the pudding, the warmed pudding freshly made from milk — use half jar sugar, Joan dear, and some whole milk always — that her mother stirred up to take the bitter taste of the dog’s cookie away.

In Mrs. Rutzel’s gaze, her blue shining eyes, Joan feels her own disbelief at the hours spent relegating things, damn things, clothes and books and tchotchkes, and all the while it was the dog. The snowflakes have accumulated now on Mrs. Rutzel’s black hat, her black-covered shoulders, each flake so different than the next, yet with the heat of Mrs. Rutzel’s body, the flakes attach to each other and become a scarf knit in white just before they turn to droplets of water and time becomes fleeting liquid embers that burn through a mass of congested heartbreak. “I didn’t know.” I didn’t know! But she understands there is nothing more to do, as Mrs. Rutzel walks back to her car, saying into the falling snow, “No dog. No Leyke. Poor hintele.”

“Wait. Wait,” Joan yells as Mrs. Rutzel opens her car door. Joan holds her hands up to the air as if her open palms to the sky and to God as her witness can stop time. Joan runs back into the house; she yells one last “Wait, please” to Mrs. Rutzel.

In the house, Joan grabs the needlepointed pillow. Out to the car, slipping once on the wet walkway, she is breathless and crying when she reaches Mrs. Rutzel.

“For you,” she says, gasping bits of cold air, “please, for you.”

Joan hands Mrs. Rutzel the pillow and hopes she doesn’t notice the small yellow stain on its backside.

“What is this?” Mrs. Rutzel says, although to Joan it sounds like Vos is dis? And the sound of the hard v stings.

Please, Joan is thinking. Take this pillow. Forgive me the dog.

Joan bends into the car and embraces Mrs. Rutzel. She holds onto the wool of her black coat, and she whispers into her ear.

“My mother was from Zloczow.”

Inside the condo, Joan puts on her coat, her scarf, and tries to shake off the chill before she goes back outside. She turns off all of the lights. She unplugs the small floor heater. From her purse she finds a black Sharpie pen and writes in thick letters on the side of the box Take it all. When she leaves, she makes sure the door is unlocked for the Salvation Army and then she is gone without ever looking back.

Erica W. Jamieson writes fiction and essays. She is at work on her first novel.