by Merissa Nathan Gerson

Becoming a Man in my Family

In a hot tub in California I met my cousin Ruthie for the first time. I had known her my entire life, but never like I did in our bathing suits, in the steam, family ditched poolside. We were there for our cousin Mara’s Bat Mitzvah, the whole family, gathered exiles from New Jersey, Florida, Connecticut, Washington, DC, Italy, Argentina and California.

In a hot tub in California I met my cousin Ruthie for the first time. I had known her my entire life, but never like I did in our bathing suits, in the steam, family ditched poolside. We were there for our cousin Mara’s Bat Mitzvah, the whole family, gathered exiles from New Jersey, Florida, Connecticut, Washington, DC, Italy, Argentina and California.

Family time, back in the day, was always the same. There were the men–and then there was everyone else. As I got older, particularly when I became a Women’s Studies major, the Gerson boys’ club became the bane of my Jewish existence.

Why? Because within my home growing up in Washington, DC, my voice was honored as equal to my father’s. At Shabbat dinners my father would invite political powerhouses, writers and rabbis to the table and I was not only given permission, but pushed and encouraged to represent my own views in well-articulated arguments. I was asked to tell about Job and his struggles with G-d, or my views on Arabs and Israelis or social ethics or international politics. I was encouraged to see myself as one of the boys, as a man really.

Except at larger family gatherings.

This was when the old country came in. From Poland to New York, all those tough male cousins who got in street fights and needed my father, the biggest of all of them, to intervene. No matter how evolved or covertly feminist my immediate family had become, in my Jewish post-Polish extended family I became a mere “girl,” and an invisible wall formed. I remember one cousin addressing my brother, both of them Columbia alums. My brother got stories on how to put wine on the heater to get drunk off of alcohol air, or even was asked to engage on topics of religious morality. If I tried to enter the conversation, it was clear it would require something of a third ear. Akin to using auditory blinders, a filter was activated to blot out the female voice when more than one male engaged in conversation.

This was when I discovered my cousin Ruthie. Together we stripped off our tights and our hand-made bat mitzvah outfits, courtesy of my Holocaust survivor seamstress grandmother, only to soak in the heat and sweat out all the chauvinism we could. Ruthie was the first woman in my whole life to see what I saw–that we weren’t allowed in the conversations. We vented unabashedly and the salve of solidarity soothed my system. Ruthie also knew that stories of women and drugs and violence were reserved for the boys, and that violence and cruelty towards women were often permissible in the boy’s club lexicon. At age nineteen, we were naming the beast, together, for the first time.

I have since become a writer with a penchant for Judaism. I’m spending the year at the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, and am en route to many more years of Jewish learning. This year, after a whole eight months with my face in Jewish text, I returned home to finally be treated like a man. Not just in the quiet and hidden Shabbos meals with my parents’ liberal or neo-con friends, but even this time, a man in front of the whole extended Polish mishpuchah. Somehow a year of Torah study bought me the ticket in. In my father’s study, he, my brother and I studied and read the story of Exodus together from the text for the first time ever.

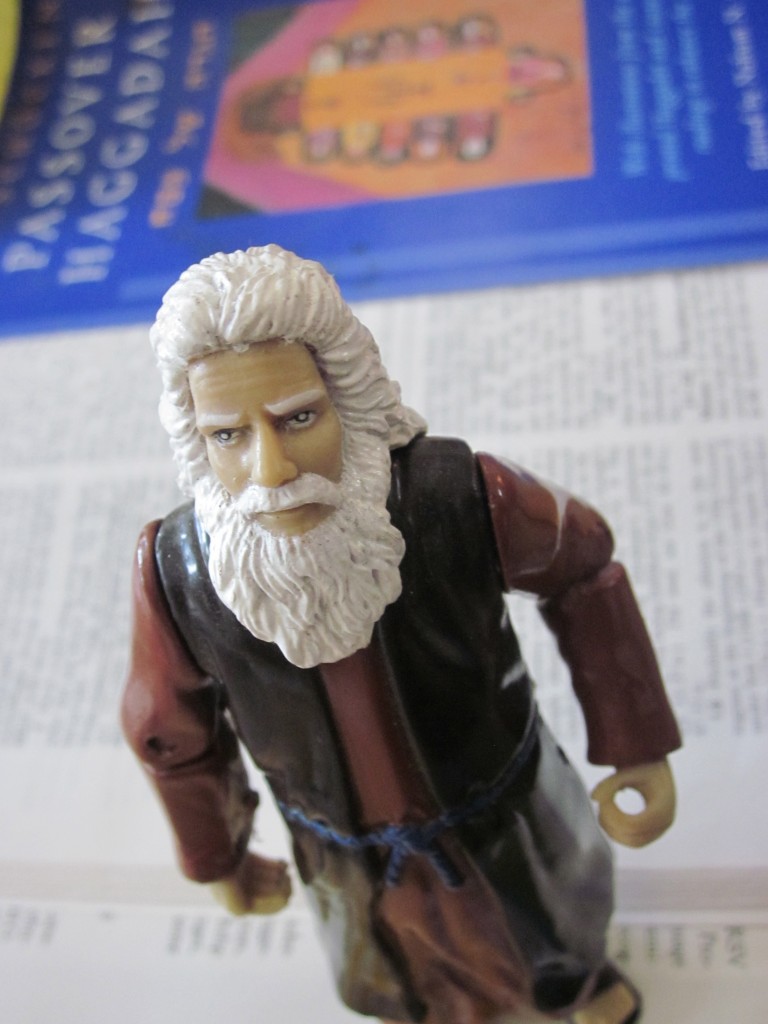

I have a complex of sorts. I’m slightly obsessed with wanting to be treated like a boy, and deeply sated at any sign of this happening. I almost reveled in the gender separatism of everything as we studied. My dad and my brother and I with the Jewish books, and my sister and my mother napping or writing or cooking. I was playing my own version of Jewish yeshiva house and was proud when I discovered that for each of us, despite years of watching The Ten Commandments with Charleston Heston and reading countless Hagaddahs, none of us had ever touched a real live Torah commentary with the whole story until now, as per my yeshiva-influenced suggestion.

So we learned new things, like maybe Moses was a murderer, or how his wife circumcised their son on the run, rubbing the foreskin into his leg.

Passover was different this year. My father, after a rough patch of minimal communication in our relationship, honored my request to lead the Seder with him. He not only honored me, but also welcomed me, even said on the phone, “This is great. The man is supposed to pass the story on to his son.”

And so, there you have it. It took two years incommunicado and a year of Torah study to not only patch up my relationship with my estranged patriarch, but to finally achieve my lifelong goal. Merissa, the Jewish son of her proud father.

Together we did what my dad called a “Whole-istic” Seder, alternating between his and my commentary. We talked about Poland, where I recently was the first to visit our family buried at Belzec, and was honored with affixing a mezuzah on the new door of my ancestors’ newly restored synagogue. We talked about the Pharaoh within us, about ditching the gender binary, about the awkwardness of undefined boundaries when it comes to history, and my cousin Ruthie sat to my right throughout.

I think about how Obama felt when he won the presidency, or how Kate Middleton felt on that royal wedding stage, and then I think about me, numbed out from the sheer enormity of leading a room full of Poles, a room full of siblings and liberals and neo-cons in the story of Exodus, all listening to the lessons I learned in a year of yeshiva in Jerusalem. I don’t know where things go from here. Cousin Ruthie grew up to be a strong medical practitioning feminist spiritualist, and I grew up to be the man of the family. I don’t know where that leaves my brother, or whether bodies have anything to do with gender, if Torah study is the mark of masculinity.

Merissa Nathan Gerson is the author of AskYourYenta.com, an advice column with an occasional Jewish bent. She is a contributing writer to the Jewish Journal of Los Angeles and is presently a yeshiva student in Jerusalem. Merissa holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, CO where she focused on post-Holocaust trauma in the body.