by admin

Remembering Mom & The Siegel Shop: Hartford, Connecticut

When Grandma was in her late 30s — old! — one of her sisters, my great-aunt Jenny Cohen, who was a social worker, said, “Becky, it’s your turn. I’m going to find you a husband.” This was right after WWI and Jenny’s job was helping young soldiers transition into civilian life. She fixed up my grandmother with a Jewish veteran — my Grandpa Abe — and together, this was in 1923, they opened The Siegel Shop. When my parents got married 25 years later, my grandfather cleaned out the cash box and gave the keys to Grandma who handed them over to my parents. They were thrilled to be done with it!

When Grandma was in her late 30s — old! — one of her sisters, my great-aunt Jenny Cohen, who was a social worker, said, “Becky, it’s your turn. I’m going to find you a husband.” This was right after WWI and Jenny’s job was helping young soldiers transition into civilian life. She fixed up my grandmother with a Jewish veteran — my Grandpa Abe — and together, this was in 1923, they opened The Siegel Shop. When my parents got married 25 years later, my grandfather cleaned out the cash box and gave the keys to Grandma who handed them over to my parents. They were thrilled to be done with it!

Growing up, I adored everything about the shop, I loved having it be in my life. At 14, I started working there, sewing labels into coats. If Carmel or Drizzle was the manufacturer, say, I’d sew “The Siegel Shop” right under the label. At 15, I moved up into designing windows. You had to dismember the mannequins — take off their wrists, their heads — which was quite a hoot. Their bodies were ridiculous: pointy, perky boobs that no female has ever had, you can bet on that! — boobs with no nipples, 20-inch waists. Mannequins were a size six or eight in those days; now they’re size two or four. I picked out the outfits, made sure they matched in the windows, coordinated jewelry and scarves. The windows had to be the height of fashion — very elegant and au courant — to draw in passersby. I also started selling at 15, for $1.25 an hour, below minimum wage — it was called “apprentice wage” if you weren’t old enough to work. I felt so grown up really, so invested in the store. I worked there Saturdays, school vacations, summers. All the time! On Tuesdays, every Tuesday, my parents would take the train into Manhattan to buy at the “apparel houses” on 7th Avenue — something I started doing with my dad (I took my mother’s place) in my late-teens.

My sister Martha, two and a half years younger than I, had no interest in the store, or in high fashion. But me… even before I was old enough to work in the store, I would take the bus downtown with a girlfriend on Saturdays, say hi to everyone at the store, go for Chinese food at Song Hays, and then go “shopping” — we never bought anything — and end the day back at The Siegel Shop, and go home when Dad was ready to close up. The first thing I bought on my own — at G. Fox and Company — was my bat mitzvah dress. Mom, by then, completely trusted my fashion sense; I remember her saying that the outfit I picked out was “perfect.” On the bimah, it was kind of a two-fer: I was stepping up into womanhood in religious terms, but I was also stepping up to represent my family’s fashion sense, reinforcing my parents’ role — and The Siegel Shop’s — in the community.

In college, the first thing I wanted to do when I came home on breaks was go to the shop. I couldn’t wait to see “the girls” — the seamstresses, Mrs. Killian and Mrs. Hometh, who worked in the big sewing room in the back; Miss Henrietta Ginzberg — “Ginzy” — a single gal in space shoes who worked as a saleswoman for my parents for over 50 years. I loved these women. I felt like a princess. They’d say, “Oh Janie, we have such wonderful new things! You need to try them on!”

I was also in college when my parents started sending me to buy on my own in Manhattan. The first time I was terrified. I walked into a “house” and they told me that I had to buy 10 pieces minimum of each outfit. We were a small store. We couldn’t handle that. I called my dad long-distance and he said, “Do it. Pick out what you think will sell. Have confidence, Janie.” The stuff I picked out — I could still describe each piece to you, it was Albert Nipon — sold like hotcakes. We had to re-order. I felt like Queen for a Day.

My mother was a great saleswoman. She had a fashion sense that was, well, just gifted. She was very honest — she wouldn’t let a customer buy something that wasn’t flattering. Actually, she could be a little cruel. She’d say, “You can look better than that.” She always called my father “Mr. Matlaw” in the store. As in, “Mr. Matlaw, do you think you can get this in a size 10 for Mrs. Epstein?” She felt she needed to act like an employee. It was interesting. If a customer tried on something with a slight irregularity, a plaid that didn’t exactly line up, her quip was always, “A man on horseback wouldn’t notice.” We had a lot of well-to-do Jewish customers. If one of them said, “Bernie, I don’t really need this,” my father would say, “Selma, this isn’t a store for the needy.”

It was a different era. Customers came in, they sat on lounge chairs, my father brought them cups of freshly brewed coffee. They would sit there drinking coffee and the salesgirls would bring out outfits to show them, one at a time. We sold bridal trousseaus for honeymoons. That meant one outfit that you’d wear on the plane — a stylish dress and a jacket to match; daywear for the fancy resort you were going to — beautiful white linen pants, a silk blouse. You’d have eveningwear. Your bathing suit cover-up. You bought a “costume,” meaning that three or four pieces all went together. My mother worked part-time, so when my Dad got home after work, they’d talk to each other. “Mrs. Higgins bought six pieces.” “Mrs. Weiner is such a pain in the ass!” Both my parents knew every item in the store: Junior Sophisticates, Chetta B, Junior Accent, Ann Fogarty. They were among the very first to carry Calvin Klein in the ‘70s.

These were lifetime customers. These were relationships! There was a Mrs. Hayward who could no longer drive. My dad would pick her up, take her to lunch at The Steak Place, she’d shop… . There was a woman with polio, an aide to Congressman Sylvio Conte, who drove down from Springfield, Massachusetts, a few times a year. There was the married Mafia guy who brought in the girlfriend and paid cash. There was Dr. Dowling. Mom always waited on him. He came every Christmas and would buy his wife five gorgeous outfits. It was a high ritual, very exciting and fun when Dr. Dowling came. Mrs. Dowling was a very good-looking woman. We all got into it. At my mother’s funeral, there were so many old customers. They loved my parents, loved going into the store. Mom had meant something to them. Mrs. Dowling made a shiva call. “Doris,” she said, “dressed me. She was a spectacular saleswoman.”

When my mother died — it was a brain aneurism, very sudden — we sat shiva in Hartford for two days, the house was packed with family and friends, and then I came back home to Boston. I’m divorced, my kids are in college, and I felt so alone. It was so painful. Which is crazy, really, because I have so many close friends. But I was aware — again — that I didn’t really connect with my new shul. I hate that. I didn’t have a ready-made shiva minyan. I didn’t want to ask people for “favors.” I don’t know. I didn’t have anyone to say Kaddish with. So I would get up by myself, go to the window — I don’t know why I went to the window — and say Kaddish. It felt like a big void.

That first week, I thought about Mom in The Siegel Shop a lot. That surprised me. About how capable and handsome she was. I was proud of her. She carried herself beautifully. About how I used to get to try on all this clothing. Whatever I wanted. When I got older, I would just take things. It was like a girl’s dream. Seriously. In a relationship that had its share of mother-daughter difficulties, Mom and I really shared this thing — an “eye” for fashion, an excitement about clothing and style, a knowledge base. For years, I intimately knew my mother in her role as a professional, not just as a parent. I worked with her — I loved her “office,” I appreciated what she appreciated. Through the shop, I had shared so much with my parents.

And then, fairly soon after my mother died, my father, who likes to get things done, said to Martha and me, “I think we need to start going through Mom’s things.” My mother was always a little critical of women who had a lot of clothes — she’d famously say, “I’d rather have three or four nice outfits than a closet full of clothes” — and so Martha and I were shocked — shocked — when we started going through all her possessions. It was like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with the brooms — oh my God, the basement was full, the closets were stuffed. There were clothes and clothes.

First we thought of the Hadassah Shop, because that’s where Dad would take unsold clothes at the end of each season. Siegel’s was a four-season shop; merchandise had to keep moving. And then we investigated “Dress for Success” — a program that helps poor, unemployed women enter the workforce, prepping them on how to dress, how to do a job interview. They needed certain sizes, bigger sizes, and Mom was a 12. Sometimes a 10, sometimes a 14. Martha took a huge haul over to them, and we thought, “Mom would love this! Women in the workforce and looking good? That’s what she was about!”

So then Martha calls and says, “Janie. there is still so much stuff. You and I have to look at all this stuff together — this is so much a part of who Mom was. Why don’t I just bring all this stuff up with me to Boston?” We had wrapped up dozens and dozens, tons, you have no idea. A lot. We brought them all into my house.

The first thing we did — Mom had a lot of costume jewelry, semi-good jewelry, pocketbooks, scarves — we sat down with it all and thought of every woman who was close to Mom, and set aside, oh, at least 35 items, 40 items. I am not exaggerating. My mother’s dear friend Ziona had given my mother a pin for a birthday; we gave it back. My father had bought my sister and mother and me three Elsa Peretti-like hearts, we’d wear them at the same time — it was a sweet thing that he did. So now we had this third necklace — we gave it to my cousin JoAmy who lives in California; she had lived with us for a summer during a tough adolescence; she was like the third sister.

We’d see something and we’d be, like, “Oh, isn’t this great for — whoever! Sarah! Aunt Sybil! So-and-So!” It felt so good to do it with Martha, sisters doing it together. It was like a part of my mother that could be passed on. It was grief therapy. It was like scattering ashes, a way of spreading her out. When it came to her socks, however — her feet being in her socks––“I can’t deal with it,” I said to Martha. “I can’t deal with it. It touched her feet.” It was too close. I couldn’t give away socks. And the make-up, the moisturizer? Using someone else’s make-up feels really intimate. I don’t know. It’s still in the bathroom; Martha and I use it when we go home.

We were going through memories, our memories were tied to clothing. Oh, remember this beige leather skirt Mom wore with snaps all the way down the front? She had a love of two-toned spats, of shoes that tied, that looked manly but with pointy toes. My father loved these, too. “Oh God do you remember Mom wore this to Nate’s bar mitzvah?” A lot of black-and-white. She liked dark, striped pants suits; they made her look elegant.

So before I knew it, I took two rooms and was turning them into the Siegel shop — my son Ben’s room (he was at college) and the guest room. I emptied the closets, hung suits outside the closets, hung things wherever I could. I set up the “store” by genre — I folded all the sweaters in neat piles, by groupings: blouses in a closet, pants folded in threes on the bed, hats. Drawers pulled out. It was very appealing to look at. All the shoes lined up on the floor. I was 15 — designing the windows again, picking out outfits, making sure that everything matched from the sidewalk. Coordinating scarves; all very haute, to draw in passersby.

And it was funny, because I didn’t have any energy for sitting shiva, for going to the synagogue to say Kaddish. I was so depleted, and these things just were not in any way helpful to me. But here I was, crying and paying tribute to my mother by buttoning a blouse on a hanger, by giving a cuff a little yank. And then I realized that I wanted 12 of my friends to come over and be in one big “dressing room” — all together, laughing and crying and dressing and undressing. The idea felt comforting to me, it felt very comforting — bringing these parts of my world together. For me, this was going to be shiva.

The day of my “party” — it wasn’t a party; it was a ritual, it was an I-don’t-know-what-it-was. It arrived. It was pouring rain. And I had baked, there was freshly brewed coffee — like at The Siegel Shop. I talked about my mother and said a shehechiyanu. For a new ritual, for the newness of all of us being here together. It was a new beginning, a “pass through” — like the mikveh — you pass through and it’s a new beginning. I needed to cry. I felt like… this is a good way for me to cry.

And people tried this on and that on, which for me is like the ultimate — because I do love helping dress my friends and seeing them look put together. I love that! And I channeled my mother:

“No, that’s not you. You can look better than that.”

“Mr. Matlaw, can you get this in a 14 for Mrs. Kaplowitz?”

“A man on horseback wouldn’t notice… .”

I was helping my girlfriends put outfits together. It meant more to me than I could have ever imagined. I was connecting my past with my current life. Searing into my heart, it felt like that, that my mother lived on — in my friends, in clothes, in me. I was making something permanent: that’s what it felt like. It was such a help in moving through the grief.

I got teary-eyed to see an outfit of my mother’s on somebody else. It was sad; it was a mixed bag; it reinforced that, look, she really truly isn’t here anymore. But it was joyful, too. Yes!—this Drizzle coat will live on in perpetuity.

The most powerful thing was giving more than 50 items — can you believe this? — to Julia Dunbar, whose office, until recently, was right next to mine. She was my mother’s body, she fit perfectly. She literally came into work every day with an outfit of my mother’s on! She’d say, “Look at what I’m wearing!” and it was both weird and nice and it always looked great on her. My mother would have loved the way Julia looked in her clothing.

The thing about my mother’s clothes is that they physically touched her; and now they are touching other people. This is what she did! She touched people — literally and figuratively; clothes were her vehicle for achieving that.

My mother, who was a very practical person, did not believe in therapy — she thought it was very self-indulgent — but she understood deeply the importance of people feeling good about themselves, and the role that dressing well could play in one’s life. I think this is how she wanted to see the world: She wanted it to look good. She wasn’t an aesthete, she was not into beauty. She liked tidiness, she liked organization. She liked to look at people “well put together” — this was her aesthetic. She liked to help others achieve that; this was an important role for her. For her, for Mrs. Epstein, for Mrs. Dowling. I didn’t fully understand this until her funeral, and at my “give-away” I understood it even more deeply.

My “give-away”… well, ceremony. It was an enactment — like Passover. It was a re-enactment — like those living history people at Plymouth Rock with the dress-ups: Hear ye! Hear ye! The Siegel Shop — 1923-1988! I don’t know. It was about three big things in my life. My mother, my girlfriends, and clothing. Clothing… is huge in my life.

Jane Matlaw, Director of Community Relations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, is involved in social justice work, and serves as personal shopper for her girlfriends.

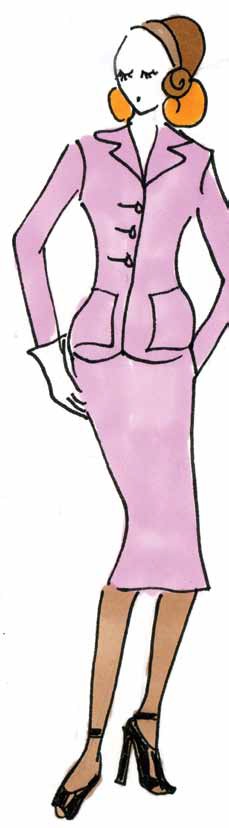

Ilene Beckerman is the author/illustrator of Love, Loss and What I Wore and other books.