by admin

Young Israelis Make Waves In NYC

Ofri Cnaani: I’m a visual artist, working mainly in video and drawing. I was born 1975 in Kibbutz Cabri, where a few individuals had struggled early on to have it accepted that their membership, their contribution, would be cultural. They staked this claim in a place where the discussion had been only about bread and butter. Cabri was a special setting, both a dogmatic kibbutz lifestyle and a very large community of artists. I grew up under the great influence of my grandfather, Yehiel Shemi, who was a modernist sculptor and who was very orthodox as a secularist. I’ve been in New York for six years, since coming to get a masters degree at Hunter College.

Anat Litwin: I was born in 1974 in Madison, Wisconsin, and I grew up in Berkeley until I was eight; then I moved to Israel until I was 27. I got my BA at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. A week after I finished my masters degree — at Hunter, like Ofri — I became director of the Makor artist-in-residence program and the director of the Makor Gallery of the 92nd St. Y, in Manhattan, and continue to work on my own independent projects. I am here in NY seven years.

Gili Letzter : I was born 1980 and grew up in Kiryat Hayeem, I studied film at Camera Obscura School in Tel Aviv and I’m now doing an MA in documentary film at City College. I’ve been in New York for five months.

Nivi Alroy: I was born in 1978, and I had quite a suburban childhood in Herzliya, but I relate to Ofri; my parents and grandparents are militant atheists. I graduated the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, Atelier 17 in Paris, and did my MFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York. I gradually moved from creating experimental animation to sculpture and printmaking. Today I have a studio in Brooklyn. I work on both individual and collaborative projects, exhibit in galleries, alternative spaces and teach art and comics. I am here for over two years.

Mika Hary: I was born in 1986 in Kiryat Tivon, but went to school in Kibbutz Yagur because of its music program. I got into jazz in high school and started to perform then. My military service was in the army band as a singer; after the army I was on the Israeli version of “American Idol.” I had a dream of coming to New York since I was in high school. I am in a combined BA and BFA program at New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music and the Lang College for Liberal Arts.

TAMAR: With so much going on politically and economically in Israel in your lifetimes, how did you become artists?

OFRI: I grew up in an environment where the artists distanced themselves from a classic Israeli identity in favor of a more universal language. They believed that artists in Israel or New York or Berlin can work together or at least speak the “same language.” While in other aspects of my life I am very involved in Hebrew culture and Jewish culture, my art deals with contemporary and personal issues but not Israeli ones. When I arrived in New York this question was a big conflict for me. In New York it is easier for people to think about you if you bring an Israeli voice, if you have a narrative that is Israeli, or that of an immigrant; your work is then seen as not so general.

In Israel I don’t think I actually had a process of signing up to be an artist. I grew up in a highly identified aesthetic environment and therefore entered very easily into the work — and the genealogy — of the Israeli art world.

TAMAR: Ofri and Nivi have named a very new phenomenon in Israel: dynasties, genealogy. What about the artistic aristocracy of the kibbutz? Kibbutzim made a place, traditionally, for exceptional artists — at least for male artists — enabling them to be different, an authorized enabling. A recent exhibit at the Haifa Museum of Art curated by Tami Katz-Freiman, “Boys Craft,” showed work by 41 male artists using traditional women’s craft such as embroidery, knitting, weaving and papercutting. What about the gender question?

OFRI: It is still an enormous struggle.

GILI: Even in the film school.

MIKA : And in the army.

OFRI: In the art schools there are 70% women, in Bezalel maybe it is 50%? Okay. But at the end of the day, at Hunter, when we thought of the students who “made it,” they are men. When I go to see exhibits, I see much more art done by men.

ANAT: That’s true in Israel, too.

TAMAR: In terms of education for the arts, besides jazz, Israel has 40 programs in dance in regular regional high schools — it is a very dancing country and produces wonderful dancers who are integrated into the best dance companies in the world today. Then again, most of the students are females, many of the leading dancers are male.

ANAT: In my work I’m dealing now with the question of childhood and home from an autobiographical perception, and the transition from being an American to becoming an Israeli — which for me happened at age eight with a clash of cultures.

My parents separated when I was four and my mom, myself and my two brothers moved to live in the student dorms at Berkeley, where my mother did her Ph.D. in social work. We

lived with Mom’s girlfriend, Martha Shelley, so I grew up with two moms. Martha is an American writer and poet, and a real politically conscious individual who was highly involved in the feminist and anti-war movements. She was a leader in the ‘60s and was even arrested at a protest for women’s rights. So I went from a relatively typical nuclear family unit to a completely different family unit. Aunt Martha had a great influence on me during my early years. She was the first person to buy a work of art of mine when I was six, and those five dollars, that gesture, had an enormous impact on me. Martha encouraged me to speak the language of art, and she also supported my artistic education. To grow up with an aunt or relative like this, who is the “other,” and not just having the direct parental relationship with mom and dad, made the conversation very meaningful.

And then, when I was eight, there was the transition to Israel, when Martha stayed behind and we came to start a new life. My mother was open about being a lesbian. It was very natural, all through the years — not hidden, not a secret — but also not especially spoken about. For me the transition from the diverse and open social environment of Berkeley to the Israeli social environment of Haifa in the 1980s, very closed-minded and stigma-driven, was a pretty big shock.

Today there are more alternative family models, but I don’t know other adults who grew up in a similar home setting like mine. In my work now I am interested in the structure of the nuclear family — what does it mean when the gender roles are questioned ? This exploration comes out in my recent series of paper cut-outs in which there is a playful gender game that is linked to wider social and cultural questions. Is it even possible to decide what is feminine, what is masculine?

I am also dealing with the question of “home” in different cultures through the annual homebase project (www.homebaseproject.com).

TAMAR: You were exposed to forms that were self conscious, radical choices.

ANAT: To me the radicalness was actually expressed by the exposure to a genealogy of very powerful strong women; that is very much part of my consciousness. It’s related to the music I listened to: Nina Simone, gospel singers, Black queens… As a girl growing up, I had help in noticing and naming strong, independent women: writers, artists, musicians, and naming my own strengths, physical and mental. To esteem the female voice — well, in those years in Israel this was not common.

GILI: The environment I grew up in had no connection with art or any kind of inspiration. Nothing. Not at home and not in school. The high school I went to was like a factory without many possibilities.

The only place that was a little open and was a dominant influence in my life was the socialist Zionist youth movement, Tnuat ha-Noar ha-Oved, where during our regular educational activity we also created plays and other staged projects. This was practically my only artistic outlet. When I got to 12th grade, for some reason the high school had a tradition of an elaborate graduation show. I wrote and directed the play, and was involved in every aspect of the production, writing text and song lyrics, directing video clips, casting, producing. The show was held in the amphitheatre of Kibbutz Lohamei Hagetaot with more than 100 partcipants on stage. That was my first contact with directing, theater and film. I was very drawn to it, and I thought maybe when I was older I would do something with it.

But during that period I was a socialist, and I dreamed of changing the world. I did a year of national service, I lived in a commune, and I was a youth guide; then our whole group went into the army together to the same unit where I was a soldier-teacher and a youth group leader. I was all the time working in education, with new immigrants, children from very low socioeconomic strata.

This youth movement, Noar Oved, is pretty extreme. There are members who are adults their 20s, 30s and 40s who live in communes, a kind of island inside Israeli society. All the time we had seminars, we studied the writings of Yosef Haim Brenner, Berel Katznelson, Martin Buber, and many other revolutionary socialistic ideologues, and I forgot that there had once been art. I was sure that I was going to change the world, and live in the commune my whole life. For me, the typical Israeli trip abroad after the army was not an option, studying was not an option. Then, at some point, about a year after finishing the army, I felt very suffocated.

Our commune was in Tel Aviv, and someone there reminded me that once I had thought about film. I had entirely forgotten. It turned out that the Camera Obscura school started a class in one month. My parents really wanted me to leave my socialist life, so they supported my studying. And that was it. I began studying filmmaking and it was my salvation.

During all the years of my adolescence, I was seeking meaning and belonging — and I went around with a kind of uneasy feeling inside. When I started to study film I felt for the first time I was actually living in the present tense. Suddenly I felt that if I shrink my goals a little, I have a chance, I can really do something.

OFRI: But it seems to me that documentary film is also work with a social agenda…

GILI: Yes, there is no doubt that remains in me, but it had simply been too heavy a burden. They weighed us down in the youth movement with how terrible the world was, and how much we could change it, and then they threw us out there — all the Noar Oved branches are in the most remote places, with no bus to get there. How can you change the world like that? [LAUGHTER.]

During my army service, I was working in a Jewish and Arab school in Jaffa as a guide. After leaving the movement, I started working in that school as theater director. I made a close connection with an Arab boy, Tony; I had been his youth leader and later on his graduation show director. I made my documentary film about him because he went and did his national service with the same youth movement, living in a commune with another 20 Jewish members and leading Jewish youth groups. I made the film about his identity conflicts as an Israeli-Arab who chooses to be a part of a Zionist Jewish youth movement. The film was in the Doc Aviv Film Festival, Warsaw film festival, and I went with it to Beijing film festival, which was wonderful.

TAMAR: When Gili speaks of it, it sounds almost fictional to me, that a girl born in 1980 supplies an unproblematic narrative that has been told again and again year after year in the annals of socialist Zionism: that there is an idea, an ideology: It is possible to change the world. It is necessary to change the world. Young people must change the world. You have to leave home to go to another place, to search it out, to live there, to change it. And to be disappointed. That’s a part of the story. [LAUGHTER.]

To see grown up people who refuse to grow up continue living in a commune. And that over and over again in historical memory to live in a commune or a kibbutz, to be a socialist, to be in a youth movement, to live in an urban kibbutz, to change the world, is like a grid in the Israeli memory. Each time new social forms are developed they make new variations on this memory.

NIVI: So now we move to Herzliya. My grandfather from my father’s side, Yehuda Alroy, was a member of the renowned art group, Ofakim Chadashim (New Horizons) and wrote art history books. From my mother’s side, it’s altogether a story of a Zionist dynasty. My grandfather from my mother’s side, served in the Hagana (the pre-Statehood militia). And here’s another story about our ancestors: My mother was in the army in 1958. One day they took her to an orchard, put a basket of oranges in her hands, three photographers came and took her picture. Since then she has been on the half-lira note. [Nivi’s mother’s portrait from the half-lira note forms the logo for this section.-Ed.]

Anyway, art was very much there all the time. Always there. At the age of two I was drawing on the walls. It wasn’t a decision.

For many years, as an artist, I was very interested in the female body. My relationship with the politics of place was too complicated to attend to. While I was at art school, it was a time of many suicide bombings in Jerusalem. I started to volunteer with B’Tselem (Israeli Center for Human Rights) and Taáyush (an Israeli and Palestian peace group). And I remember myself, in the cafeteria, handing out pamphlets about the state of human rights in the occupied territories. The students were ironic, cynical and indifferent. It wasn’t from a right-wing Zionist position of saying you are betraying us. It was: Why are you doing this? Why not give up already?

You go home and you feel that you have to apologize for your curious point of view, that you are always at some kind of extreme. We left Israel because Assaf, my partner, was going to start a post-doctorate, and I wanted to go to Paris, to work in a certain workshop for etching and printmaking. We lived in Paris for two years.

TAMAR: Did your politics find expression in your art?

NIVI: When I got to New York for graduate school, suddenly I found I couldn’t ignore the fact that I am Israeli. My work went from an interest in the body, and myself, to an interest in place. Not just any place, but Israel.

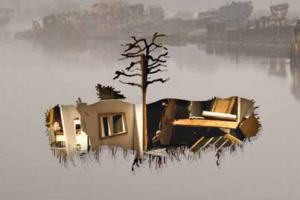

I began to interview all kinds of immigrants. I think I asked them about their immigration in order to answer questions for myself. Then I compiled an artist book out of their answers and called it, Never Trust a Memory Tree. Nowadays, I am working on stripped, exposed houses. The light and the landscapes are Israeli, and the houses have to contain some Israeli personal features in order to portray a larger, universal experience. When you create here in New York as an artist, you stand as an Israeli. I often feel obligated to explain the complexities behind the headlines, but that’s not what people want to hear. They want to know who is the “good guy”and who is the “bad guy.”

TAMAR: Every act can be seen as a political act. Certainly in the work of women, certainly in the work of feminist women.

MIKA : All of you can say exactly what you are involved with. I’m only 21, and I feel I am just at the beginning of my journey. While around this table I am the youngest, in school I’m considered “older” and more experienced. Americans say, What? You were in the army? And then I say it wasn’t “real” army, after all, I was in the army band; it wasn’t a big deal.

I didn’t have the experience of searching or suddenly discovering music. As early as I remember myself, I was always singing. I was attracted to the spotlight, and not just the music. The love of the stage and the life on stage on the one hand, and the search for depth, too; not just the spotlight, but to really say something.

Another conflict is the combination of the creative and the practical worlds. The mixture of using my intuition and musical ear and also the very theoretical side of my brain. Sciences were very strong in my family — mathematics, physics. When I listen to music or look at music, many of the connections I find there, creative or technical things, and the way I explain them to myself and then to others is very analytic.

ANAT: Who are some of your musical inspirations?

MIKA : I grew up on classical music and always Israeli songs, from Chava Alberstein to Shlomo Artzi, Gidi Gov and Arik Einstein. The by-now cult children’s album that I grew up with was HaKeves HaShisha Assar (The Sixteenth Lamb) with poet Yehonatan Geffen’s beautiful lyrics. Yoni Rechter’s sophisticated but not intimidating compositions for this album — performed by many of Israel’s best singers — set a high standard not just in my musical taste but I believe in Israeli music in general. It started with Vilenski and Argov and continued with Rechter, Shem Tov Levi, Mati Caspi, Yehudith Ravitz and Shlomo Gronich who all shaped the Israeli musical style in a very beautiful and unique way and a lot of them also started to throw into the musical mix their jazz influence.

My jazz phase started in high school. The development of jazz is very interesting in Israel. With all the Zionism, and all “songs of the Land of Israel” (a genre), suddenly in the 1980s, people went to America to study music — mainly to the Berklee College of Music in Boston — and came back with the message of jazz. They founded the Rimon School for Contemporary Jazz and then many high schools added jazz to their classical music programs — and teachers spread the word, my case exactly. When I was growing up some young Israeli jazz musicians already started to “make it” abroad. They created a level that we aspired to. It is as if they opened a gate that said: here, we (as Israelis) can make it in New York and in the world. Today it is amazing that Israeli jazz has an honored reputation even in New York. Israeli jazz musicians that made it here in New York include more male musicians than women. But this is changing following the success of women like Miri Ben Ari, Anat Fort and especially Anat Cohen, who won numerous prizes recently.

I see this combination in myself of something very Israeli — my father, who fought in the Yom Kippur war, my grandmother and grandfather in the Palmach, I feel I grew up in a house that was very Israeli — and at the same time very universal.

It’s like… Anat, you spoke of your aunt.

TAMAR: The “other.”

MIKA : In that role I had my father’s brother, my uncle, who had a big influence on me. He is a professor of linguistics at Emory in Atlanta and combines the Israeli and the universal. He was always interested in the subject of gender because he is gay. (It’s interesting that no one ever told me that he was gay.)

I have an ear for accents, pronunciation and words that people choose or don’t choose. I’m very interested in the subject of identity. So the question of New York, unlike for many people who come here goal-oriented for the music or school, for me it is much more for the social cultural experience. (That affects the musical, of course.) I can only speak of the four last months that I have been here, but I already feel all the issues as if burning, and it awakens a lot of inspiration.

Being an Israeli here suddenly feels very different: every American you speak to here, even in a casual conversation, starts interviewing you about Israel. I find myself all the time talking about Israel and its history, explaining Zionism, and all these cultural concepts… [LAUGHTER]

OFRI: “Before 1948…” [LAUGHTER]

In Israel the fact that you were in the army for two years is hardly interesting. But here? Serving in the army for two years is a story here! The fact that on the kibbutz I grew up in a children’s house without my parents — that’s a story!

TAMAR: And your sense of the possibilities here?

MIKA : I feel I came here to find this balance with my Israeliness, which is very important to me, and relevant because most of the songs that I write are in Hebrew, but also to expand the universal side of my music. A singer has a power that instrumentalists don’t, and that’s the lyrics, and the sound of a language.

TAMAR: There is also a certain advantage for women in performance, I think. As a vocalist your instrument is your body on stage, and people want to see it. There is nothing you can do about this…

MIKA : Hmmm… . I can think of some male singers who are hypnotic too… Singers from other foreign countries have created a legitimacy for singing in their own language, like Portuguese or Spanish, and I believe that there is room for some Hebrew in the mix.

GILI: I am teaching at a school of a Reform congregation, where I am supposed to be teaching about Judaism, but I don’t know so much about Judaism. [LAUGHTER.] So there is this meeting with American Jewish culture, which is a little strange to me. And I ask myself: Do I feel more Israeli than Jewish?

ANAT: It is clear to me that I am returning to Israel. It is very important to me in Israel to be socially and culturally active, to participate in bringing about change in this difficult environment, and to create an environment that is a platform for cultural and artistic dialogue. I see that as an essential need.

Another thing I want to mention is that a week ago I finished reading Herzl’s Altneuland [Zionist utopian novel published in 1902]. [LAUGHTER] Herzl invented the idea of a ship that will carry on it the best artists and philosophers from all of Europe — creators of culture — and this ship will sail every 20 years to Eretz Yisrael — to influence, bring inspiration, exchange creative ideas, and bring out a message of culture from Israel to Europe. He saw this as part of the Zionist plan. Why? Because cultured people create a state, there is no such thing as a collective without this, and artists can, and should, be the ones to lead change, and see beyond everyday reality. I find this aspect of Zionism to be totally under-addressed.

OFRI: The cultural question: I think for a long time I had two channels: study of classic Jewish texts, and the art which I chose as a career. When I was in Israel I never thought the two would be bridged. Now I am working on a story of two sisters connected to the sota, the woman suspected of adultery.

My project is a large-scale video installation that reenacts a controversial story from the Talmud. It is a story about jealousy, trust and mortal love that follows an “adulterous” woman who is put on trial by her suspecting husband while her sister helps her fight for her life. My “Sota” is an attempt to create a hybrid between ancient media and new media both visually and literally. The text can thus burst into both spatial and time-based narratives and calls into question the notion of a coherent truth.

Tremendous things happened for me here. It’s the result of a lot of hard work, and being present, and connections. How do you make a balance with more things, between some “doing” but also some “being”… .

In Israel there is a kind of feeling you have on a Friday afternoon that life relaxes a little. Here… well… this is what preoccupies me.

The first time I came to New York, I came out of the subway and I said “I feel at home. It is so big, and I don’t know a single person. Phew! No one knows me and I don’t know anyone. Wonderful!”

My question today: Is it possible to be a citizen of the world? One of the subjects raised here was the fantasy of New York. It’s like an elastic, you run and you run and run and suddenly you feel the pull back, you feel the Israeli presence. Then when I come to Israel I am from New York, obviously. [LAUGHTER.]

ANAT: The power of a place/environment is very strong . When we go outside on this Friday afternoon we will feel it, it’s powerful in an unbelievable way, the vibe of the people in the streets of New York, compared to the environment in Tel Aviv at this specific time. People say things are the same everywhere, but the difference place makes in your day-to-day life is very influential.

TAMAR, and EVERYONE: Shabbat shalom.