by Guest Blogger

Green? Or Greeneh? Some Earth Week Reflections

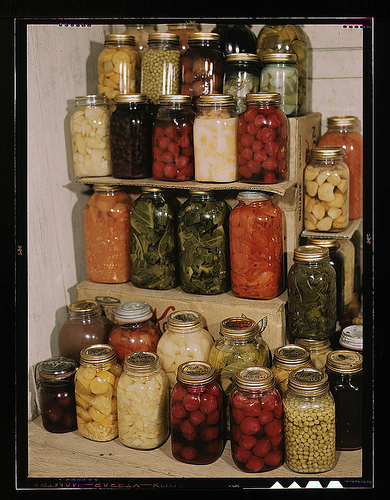

Photo via Library of Congress Flickr stream

Growing up, green was the color of the aluminum siding on our house and of our painted garage, teeming with a full assortment of scrap—wood, metal, plastic, heavy paper and anything else that might somehow serve a future purpose. Green was the color of the lawn I often mowed, watered only when needed and early in the morning. My Girl Scout uniform was green. And so were the glasses filled with warm tea left out every morning for me and my sisters, the intentional love-filled leftovers from the big stove-cooked pot of tea our Dad filled his Thermos from each day before heading to his job at Gleason Works in our boat-sized American-made Chevy Impala, which he could fix himself.

Green was a shade of envy, too. Envy of the kids whose sandwiches were packed in throwaway Ziploc bags instead of bulky Tupperware that had to be schlepped home. Envy of all the other moviegoers, who got to socialize while waiting on line for buttered popcorn while we rustled through an over-stuffed tote to access a re-used plastic bag full of white kernels, air-popped at home. Envy of my friends whose families hired plows to remove their snow while we bundled up in hand-me-down snowsuits and shoveled all day.

It was envy of my classmates and friends whose parents had gone to college, didn’t have accents and weren’t mistaken for grandparents… and it was envy of those who had grandparents.

Growing up the daughter of Max Widawski, survivor of 11 concentration camps, I am the first-generation American-born in my family. Though my mother was born in Canada, she grew up speaking Yiddish and could hand-chop homemade gefilte fish as if it (and she) came straight from the Old Country.

I often feel like I’m a different generation than my peers. I sometimes struggled being the one who was different, the only one in my class at private school whose parents weren’t professionals. At the same time, I loved being around others who shared my father’s accent, knowing deep down that the commonalities went far beyond their mastery of English. I felt tremendous pride, a pride that intensifies as I understand more of my experience growing up surrounded by “greeneh” (translated from the Yiddish as “greenhorn,” pronounced with a guttural gr and an Eastern European accent).

While my friends’ moms were making gourmet soups from recipes in store-bought cookbooks, I watched my mom chop knubel (garlic) for p’tcha, a jellied meat dish made from calves’ feet. When lemon scents infused the air of kitchens recently scrubbed by my friends’ cleaning ladies, I would think about the vinegar concoction our family used to clean our floors, ourselves. Others would go through rolls and rolls of paper towels; we would find multiple uses for each sheet. When I continue these practices in my life today, as a woman in my 30s, my friends comment on how “green” I am.

My bicycle is my primary mode of transportation. I, too, clean my apartment with a homemade vinegar concoction, and I rarely buy new clothes (why bother when so many others clean out their closets each season?). So why do I cringe when people comment upon my “greenness”? It’s because I’m not just green. I am greeneh. When I reuse my teabags, make breadcrumbs from dry challah, scan the gems put out on the sidewalks as trash, wash “disposable” plates and take home tiny morsels of leftovers, it is because of the values ingrained in me by being “from greeneh,” offspring of someone who survived the unthinkable and who truly knew what it was like to be without. I reuse, reduce and recycle to remind myself of just how grateful I should be —and I am —for every little thing I have. The ability to find purpose and function in almost all that exists feels like a truly blessed inheritance.

I love the scene in “Crossing Delancey” where the bubbie saves the strong butcher paper (from the great hat given to Izzy by the Pickle Guy), putting it in a closet full of other rescued items that likewise have endless possibilities. In addition to featuring a bubbie I yearn for, the scene makes me think of the handmade shelves in our basement filled with jars of all shapes and sizes, a collection I couldn’t fathom explaining to my friends, whose families threw their jars away and whose homes were clutter-free. Ironically, the collections of salvaged and rescued items that occupied our home and irked me as a child have reproduced themselves in my own space. I don’t know how it happened, but I have darling juice glass- es that were once yahrzeit candles, and there are three different collections of reusable bags in my tiny New York City apartment.

Though our parents splurged on our education, much of my family’s saving and conserving did come from financial realities. But their practice was motivated by more than parsimony. It came from my family’s immigrant experience, from being greeneh. Unlike many of my schoolmates’ homes, ours always had a United States flag proudly dis- played for each national holiday. On our piano stood a photo of Michael Pisarek, our beloved next-door neighbor who served in the U.S. Marines. We had neighborhood gatherings that were potluck instead of catered —not just because it was cheaper, but to experience each other’s flavors and traditions. My father’s appreciation for this country, for community and for all we had was palpable. I often feel I’m channeling him in my own activities, from leading social justice trips in the Gulf Coast to holding up the Story Corps microphone to capture and preserve the experiences of my character-rich New York City neighborhood.

Like my father, I can find a use for just about anything. I meet my friends in parks and other public places. I love free events, both attending them and planning them. I compost my scraps at our local community garden. I shop second-hand and love a good garage sale. I make p’tcha, and gribenes too. I’m not only green. I’m greeneh.

Chana Widawski, LMSW, works with survivors or abuse and violence, leads educational travel programs around the globe, and works as a writer and consultant.