by Aileen Jacobson

Old and New Wives’ Tales

Can you imagine a movie titled “The Artist’s Husband” about a man who abandoned his own budding career as a painter so he could cater to his wife’s needs and help her achieve fame and fortune? Or a book and a movie titled “The Husband,” about a man who goes far beyond secretly editing his wife’s books so she can enjoy literary acclaim—and, oh, also sleep with many other men? And how about the spouse of a woman in a high government position who writes an autobiography that in part examines his cascade of decisions that subordinate his life to hers? Let’s call it “Not Becoming.” And then there is the television tale of the Hasidic husband who has to run away from his wife and his community to fulfill his desire to make music and to control his life. Well, that might still be called “Unorthodox.”

These gender-reversed summaries of recent works in different genres illustrate how unlikely it is that someone would write or film anything like them—unless meant as a satire. However, the just-released movie “The Artists’ Wife,” the book and movie “The Wife,” Michelle Obama’s memoir “Becoming” (non-fiction) and the television series “Unorthodox” are each serious and thoughtful examinations of the evolving role of a wife (at least in households that are artistic, educated and financially stable). Each offers at least a glimmer of hope that the role is changing. But put “husband” in place of “wife,” and you notice that our society still has a long way to go toward equality in marriage.

In the first three stories, the wives give up a lot, more or less willingly, in order to maintain a happy marriage. In “Unorthodox,” the wife never had a happy marriage. Other wives’ tales we’ve seen explored lately include the TV series “The Good Wife,” in which a woman whose husband is imprisoned after a scandal returns to work as a lawyer, starting her own firm and experiencing success, setbacks and renewal. Then there are the various “Real Housewives” series, which Gloria Steinem has called “a minstrel show for women.” Clearly, we are not going to overcome demeaning stereotypes of “housewives” anytime soon.

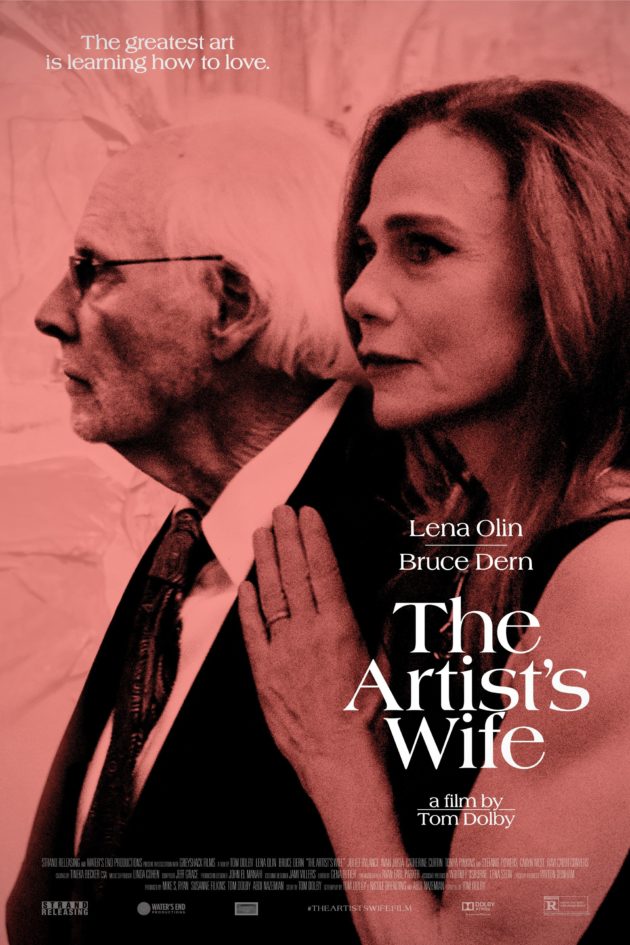

I’m a wife, too, and I understand many of these paths. “The Artist’s Wife,” which debuted September 25 in theaters and on-demand platforms such as Amazon, Apple TV, iTunes and YouTube, presents an intimate and believable variation on the supportive-wife role that started blossoming in the 1950s and still isn’t as dated as it should be. The film is a little slow-moving and occasionally flat, but it is beautifully acted, with Lena Olin and Bruce Dern giving stellar performances in the lead roles of Claire and Richard Smythson. He is older and famous. Claire, once a promising artist, has devoted herself entirely to making their glamorous life in the Hamptons smooth and comfortable for Richard. Richard acknowledges the partnership during an interview we see early on. “I create the art,” he said. “She creates the rest of our lives.” Claire smiles gamely.

She is jolted out of her cocoon when Richard develops Alzheimer’s and becomes both forgetful and abusive, mostly verbally, toward students, fans and his wife. Will she return to painting and stake her own claim to creative fulfillment? That’s the main plotline, peppered with bright depictions of strong women, including fun turns by Tonya Pinkins as a self-confident and encouraging gallery owner and Stefanie Powers (yes, of “Hart to Hart”) as an artist of Claire’s generation whose video installations are being featured at the New Museum in Manhattan—she’s obviously a success and she brims with energy.

Though I’m not aware of any artist’s wife who has gone as far as Claire in submerging her own talent for the sake of a talented husband, there are several examples of husband-wife artist marriages in which the man was far better known, including famous Hamptons-based couples Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and Willem and Elaine De Kooning, who often promoted her husband’s work rather than her own.

About the only pair where the wife is more prominent today are Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, though he was more famous during their lifetimes. In the 1930s, she would tell people that she was the better artist (she had to tell them because it wasn’t an accepted truth), but she really wasn’t recognized until the 1970s, when feminist scholars started reevaluating works by women. Also, he made immovable frescoes and she smartly made all those striking self-portraits.

“The Wife,” for which Glenn Close received a 2019 Oscar nomination, has a similar plot, except the husband (played by Jonathan Pryce), is an acclaimed novelist. The present-day part of the story is set in 1992, but the courtship of Joan and Joseph began in 1958. There was a power imbalance from the beginning because she was a college student and he was her dashing young professor.

A scene in the movie and in the novel by Meg Wolitzer shows her meeting an embittered “lady writer” who foresees her own obscurity and loneliness and a similar fate for Joan or any other female novelist. Wolitzer’s 2003 book includes another reason for Joan’s decision to make her husband shine: He is Jewish and her parents are anti-Semitic. If he becomes a celebrity author, Joan believes, her parents might be more accepting of him as a son-in-law. She turns out to be right. Wolitzer has said of her fictional character that “Joan is not a victim.” She chose her path, though bending to society’s norms at the time.

Wolitzer, who often peoples her best-selling novels with Jewish characters and addresses feminist issues head-on, fortunately came of age in the 1980s. Her mother, the respected writer Hilma Wolitzer, now 90, “was seen as a housewife who became a novelist, as if it was this shocking thing,” her daughter has said. In 2012, the younger Wolitzer wrote an essay for the New York Times titled “The Second Shelf” in which she outlined how women’s fiction is often taken less seriously than men’s.

In 2004, I wrote an article in Newsday, where I covered the book industry at the time, about the rise of female-centered books that came to be known dismissively as chick-lit. “Did the women’s movement ever happen?” I asked.

It didn’t happen for the Brooklyn Hasidic sect portrayed in the 2020 Netflix miniseries “Unorthodox.” The main character, 19-year-old Esty, is trapped in an arranged marriage before escaping to Berlin to pursue her dream of living an independent life and perhaps pursue a career in music. In Williamsburg, her occupation was to be a wife and a mother to as many children as possible. Within her community, women were not even allowed to sing in public. The series is loosely based on Deborah Feldman‘s 2012 autobiography, “Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots.” I liked the show, which follows Esty’s flowering transformation with great sensitivity. It avoids making her husband a villain, and even views his thuggish cousin Moishe, sent along to bring her back, with understanding. But I can’t say that I identified with her situation, though I guess it could be seen as an extreme version of our society’s restrictive view of the role of the wife.

In some ways, my sensibility is closest (among the four core examples here) to that of Michelle Obama, without the First Lady part or many of the particulars. A high-powered corporate lawyer when she started her professional life, Michelle Obama was always ambitious. But she adjusted her ambitions after meeting Barack Obama, shifting to jobs with a community orientation rather than a money-making goal. She was always thoughtful about the changes she made. Becoming First Lady, of course, led to the biggest shift of all, and one she made not entirely gladly. Look where it has gotten her, though. She’s no longer a practicing lawyer but she is an influential leader with her own career—and high-earning to boot.

It will be interesting to see if Jill Biden continues her job as an adjunct professor, should her husband win the presidency. She has said she would, and that would make her the first First Lady (what an antiquated designation) to hold a paying job outside her White House duties. Even more interesting: What if we finally get a female president? Would her husband be the First Gentleman? First Husband? Or just the president’s husband?