by admin

All-of-a-Kind Seder in the Time of Covid-19

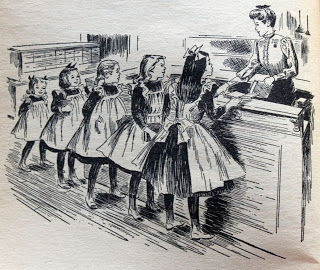

In the unfolding of COVID-19, while some friends were frantically dashing back to Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven or Ling Ma’s Severence, I reached for All-of-a-kind Family, by Sydney Taylor. It’s an old children’s book, doubly old—published in 1951 and set in 1912—about the five all-of-a-kind sisters, dressed alike and running around in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, surrounded by their fellow Jews. It was the confluence of two events that brought it to mind—quarantine and Passover.

Right there, in the chapter “Mama has her hands full,” four of the sisters fall sick with scarlet fever.

I always loved the All-of-a-kind sisters as a child. They were an echo of my life, or I was an echo of theirs. A watered-down version of their reality: One of three sisters instead of five. Jewish, but not nearly as observant. Instead of living an insular life surrounded by Yiddish-speaking immigrants in Manhattan, we lived out in the suburbs, integrated completely with our “gentile” friends. I was the sort of introspective child who occupied herself with worrying about what-ifs. What if gravity just stopped working? What if the world was ending? What if I was born a boy? What If I had been born eighty years earlier? When I read a book like All-of-a-Kind Family, I could find at least one answer—oh, that’s what it would have been like.

I always loved the All-of-a-kind sisters as a child. They were an echo of my life, or I was an echo of theirs. A watered-down version of their reality: One of three sisters instead of five. Jewish, but not nearly as observant. Instead of living an insular life surrounded by Yiddish-speaking immigrants in Manhattan, we lived out in the suburbs, integrated completely with our “gentile” friends. I was the sort of introspective child who occupied herself with worrying about what-ifs. What if gravity just stopped working? What if the world was ending? What if I was born a boy? What If I had been born eighty years earlier? When I read a book like All-of-a-Kind Family, I could find at least one answer—oh, that’s what it would have been like.

So it was soothing to pick it up now, when it seems that gravity has stopped working, and all the things that tethered me to the earth—my appointments, my childrens’ schedules, my work, my friendships—have gone away and I am simply floating. Here is something to hold onto. Passover is coming, and even in quarantine we celebrate as best we can. Just ask the All-of-a-Kind girls. Even banished to the sick room, little Gertie chants the four questions. Why is this night different from all other nights?

There is almost always a moment in the middle of Passover prep where I hear that same echo I used to hear when reading that book. It’s in the clink of the not-so-good-but-technically-

That’s the point of the Seder, in the end. We symbolically relive the story of Exodus, so that we can say that we, too, were freed from bondage. Not just our ancestors, but us too. We double back on ourselves, a mobius twist, year after year, century after century. We were enslaved, then freed. Divided, then reunited. We run to open the door for Elijah, for the no-contact deliveries, for the daily gossip of a neighbor. Why is this night different from all other nights? How similar this night is to others that have come before!

Carolyn Abram is a Seattle based writer. She has written several editions of Facebook For Dummies books and is a lifelong Jewish learner.