by admin

Raising Feminist Boys

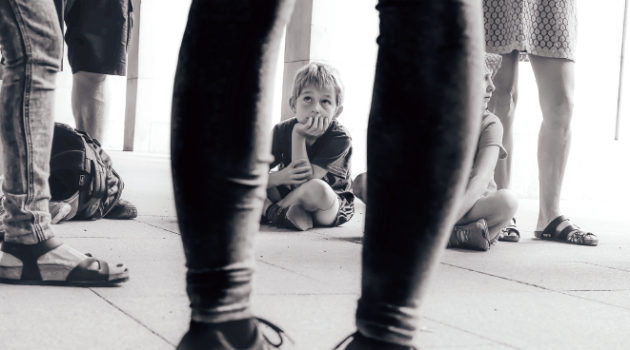

Photo by Cristina Gottardi on Unsplash.

Now that I am the mother of two sons, I find myself remembering the sexism of a male friend during my teen years. When called out on his behavior, he loved to grin and blame it on his mother. Her career, you see, was explicitly feminist. Feminist mom begets sexist son went the joke. A classic tale. Hilarious!

I have begun my motherhood journey in a world that feels blanketed by male aggression. Meanwhile, I watch my older son, age 4, begin to discover gender: he says “ladies” instead of “women,” which is extremely cute—for now. Coping with a new little brother in his life, his frustration can manifest as hitting, kicking, testing limits. I feel the weight of this moment: I know as a good, overeducated feminist that this is the age when boys’ emotional worlds begin to shrink and toughness becomes normalized. Each learning opportunity feels precarious. And yet ever since I heard the words “little man!” unexpectedly fly out of my own mouth three years ago, I have understood how difficult it is for all of us to un-learn masculinity. I swing through worry, resolve, and perverse hope. Maybe his stubbornness, so typical and so maddening, will save him as the world pressures my children into being sexist. Better to encourage them to resist social forces, right? Right?

“None of us think our sons will be the one who says something really vile in the locker room, but most will stay silent,” says Peggy Orenstein, author of the new book Boys and Sex: Young Men on Hookups, Love, Porn, Consent, and Navigating the New Masculinity (HarperCollins, $29), said in an interview with Lilith. “How do we break the silence? It takes a lot of work by adults.” Orenstein, the Cinderella Ate My Daughter author who has long been considered a cultural expert on the obstacles facing young and teenage girls, has at last turned her lens on boys—something her readers had clamored for.

In Boys and Sex, interviews with over a hundred college-age young men from all walks of life reveal a mix of progress and stagnation, consciousness paired with regression. “Nearly every guy I interviewed held relatively egalitarian views about girls…. They all had female friends; most had gay male friends as well,” Orenstein wrote. “Yet when asked to describe the attributes of ‘the ideal guy’, those same boys appeared to be harking back to 1955. Dominance. Aggression… Sexual prowess. Stoicism. Athleticism. Wealth.” Needless to say, these are the views that in their mildest form lead to everyday sexism and, in their strongest, lead to violence.

Orenstein told Lilith that this mirrors the problems she has found with girls, who are now urged to be “empowered” and run the world, while at the same time they face unaltered social whispers about body image, pleasing men, being subservient and silencing themselves. Even as feminism and LGBTQ+ awareness have put phrases like “toxic masculinity” into the mainstream, toxic masculinity persists.

Yet there is a silver lining, Orenstein said. Despite feeling emotionally curtailed, her subjects were eager to open up: “I worried they weren’t wrestling with this stuff— that was wrong,” she discovered. “Their interior lives are guarded. But they’re there.” Young men and boys need adults to help erode the limits patriarchy puts on them, just as we tackle the limits placed on young women. So where to begin?

After speaking at length to Orenstein, to several Jewish educators, and to many of my fellow parents, I came away with a few general principles for raising the next generation—with less patriarchy this time. They feel useful for parents, grandparents, relatives, teachers, and anyone who wants to see a world with more equity, kindness and caring. Will these ideas work without broad social and legal change? Maybe not. But here’s a start.

1. BEGIN WITH CONSENT.

This is the most common way that parents of young children are now trying to break the mold—discussed almost daily in parenting groups on Facebook. “From a very early time in my older son’s life we asked him if it was okay to hug him,” says Chicago mom of two boys Katie Colt, who had been a writing fellow at the parenting blog Kveller. “We felt like that was the best way to offer him autonomy over his own body and affections. We don’t force him to give hugs to us, and when he says no, we respect it. We frequently remind him to ask friends if they’d like a hug, along with reminders to him that not everyone always wants one, and that’s okay.”

“This may seem like a small thing, but I hope we are teaching him that he is in charge of his body, and so is everyone else of theirs,” she says.

This practice gets difficult when, say, your kid is covered with peanut butter and refuses to take a bath, or won’t wash his hands after sneezing. A constant renegotiation is required. But the learning opportunities are always there. “Interactions between siblings offer constant opportunities to discuss and model consent, but doing it in a way that’s not shaming is not easy, especially if you are having an emotional reaction,” says Rabbi Tamara Cohen VP and Chief of Program Strategy at Moving Traditions, which is pioneering teen support groups for boys, girls, and trans and gender-noncomforming teens, “give them the tools to know and express what they want on the one hand, while not using physical power to make other people do things.”

2. GO BEYOND THE BINARY.

Whenever possible, opening the narrow box of masculinity means showing kids when and how the gender binary can be broken down. This includes wholeheartedly rejecting a pink-and-blue world: making lots of space for trans, nonbinary and gender-noncomfoming people in your discussions, and being accepting of those around you who don’t fit into neat boxes. Right now, shifting ideas about gender give us all plenty of opportunities to expose kids to a spectrum—whether it’s someone’s pronouns, a sign on a bathroom door that says All-Gender, families with different configurations, or even a local Drag Queen Story Hour. For some kids, “boy” might not even be the right word going forward: and more and more parents are adjusting in a variety of ways.

“When other adults talk about our child liking ‘boy’ stuff, we say things like: ‘I’m not sure he knows whether or not he’s a boy yet,’” says Rosalie Roberts, a parent of a toddler in a queer/multi-racial family. Pushing back on “boy” also means treating feminine-coded play as natural for all kids: bring forth the baby dolls. “With regard to fashion and toys, many people who aim for gender-neutral for some reason gravitate toward androgynous clothing, and we think including femme clothing and toys in the mix is also important,” she says. Parents describe painting their young boys’ nails, encouraging their Frozen obsessions and pushing back on relatives’ criticism of these choices.

Julie Sissman, a Manhattan-based consultant who facilitates gender awareness workshops for educators, recalls what happened after she spoke up about gender roles in her kids’ class. One male teacher picked a pink cup to be “his” for the year, because he was newly mindful of stereotypes. “A boy immediately said ‘you can’t have that cup, that’s for girls’,” Sissman recalls. “It opened up a beautiful conversation about whether things really can be for boys or for girls.”

Creating a non-binary world opens up a huge opportunity that Orenstein sees as crucial for building better boys: mixed-gender play. Verbal encouragement when preschoolers of different genders play together can keep friendships going for longer, she says, which has a lifelong effect. This held true for me growing up. My twin brother and I were given plenty of outrageously gendered toys, but our life as smooshed-together siblings meant that we constantly used each other’s toys, and shared friends as well. From dolls to baseball gloves, my parents often had to get two of everything— and as grown-ups, my brother and I feel lucky we lived in this double world.

3. BECOME A FAMILY OF MEDIA CRITICS.

Tamara Cohen, a parent of two boys herself, has realized that talking about consent and healthy sexuality is a years-long conversation, and navigating the omnipresent media world—in which kids are “fluent”—is a key part of the task from the very beginning.

“Kids are going to be brainwashed by the culture. You’ve got to get in there and brainwash them first,” jokes Orenstein. All kids should have the same conversations about images of women that we might have with girls: if a princess movie strikes you as sexist, or the proportions of a female doll are physically impossible, why discuss this only with your daughters? We can discuss it with any kids who are nearby. Some parents go above and beyond: “I routinely change the pronouns in children’s books I read to my son,” writer Ester Bloom told me. “Why on earth do all crayons except the pink crayon need to be male, anyway?” One of the most common practices parents described to me is seeking out female protagonists for their boys to relate to. “We choose books that don’t have flagrant gender stereotypes and books such as Feminism Is for Boys and Julián is a Mermaid,” says Rosalie Roberts.

With older kids and trickier subjects, Orenstein suggests using media to open up many of the conversations around sex and healthy relationships that feel difficult. It’s a way in, whether it’s leaving an article or book lying around or (separately, perhaps) watching a particularly forward-thinking show like Netflix’s “Sex Education,” about teens and sexuality, or “Big Mouth,” about puberty.

4. KEEP UNPACKING OUR OWN GENDER BAGGAGE.

Whether it’s the scars of sexism in our own lives or received ideas about masculinity and femininity, our own feelings influence how we raise the next generation. That’s why, despite our best intentions, many heterosexual couples fall into gendered patterns around work and caregiving. Darcy Lockman’s 2019 book, All the Rage: Mothers, Fathers, and the Myth of Equal Partnership, is one of quite a few recent books to explore this phenomenon. “The couples who navigate workload equality the best, I’ve found, don’t just understand that our culture’s biases—and frankly, its baked-in sexism—result in most of the family management defaulting to the mother, but also decide as a couple that they do not want that to happen,” she has written.

So, sharing the load of caregiving and pointing out to kids when we do things that defy stereotypes isn’t good only for our marriages; turns out, it’s also good parenting. For women-identified caregivers tell your kid what you like about your job, volunteer work, or hobby. One of Lilith’s perennially popular articles, by Tamar Fox, describes her mother’s approach to “low-touch parenting,” a life oriented around her own singular passion for art that encouraged her daughters to follow suit. “Mothers, let us imagine a few hours a week when we can orient ourselves around the things we care about most that do not require diaper changes or lunch boxes,” Fox wrote.

For male caregivers, raising feminist sons means showing how soft and loving maleness can be: not only doing caring tasks, but pointing it out to kids so they see. “I model egalitarian behavior,” says writer Gordon Haber. “I make sure my kid sees me cooking, cleaning, negotiating equitable childcare.” Men are making plans even before their kids are born. Joshua Stanton, a rabbi awaiting the arrival of his first child, wrote a blog post for Lilith last year about his plans to take significant time to care for his baby to start the parenting cycle on more even ground. “All of us can do more to change gender norms, especially around parenting—especially men,” he wrote.

5. EMPHASIZE EMOTIONS.

Getting men involved, to Orenstein, is crucial for “breaking a cycle.” She says that the young men she interviewed directly spoke of limits imposed on them by male figures in their lives, specifically fathers. It wasn’t that these men were violent or angry or demeaning, but rather that they left to women the emotional connection with their sons.

“Adult men have to be engaged in this work, whether it’s a father, uncle or friend,” says Orenstein. “It’s so important that adult men remain connected in an accessible, intimate way. What the young men I spoke to said often was, ‘My dad’s not sexist or homophobic, but I learned not to have these conversations with him.’” She said, “Men need to talk with the boys in their lives about what emotional accessibility means, what vulnerability means, what true courage means.”

My fellow parents and I are trying hard to use words like “sad” instead of “mad” with our sons. “I never tell my son to stop crying if he’s upset. Sometimes I want to!” says my friend Emily Dreyfuss. “But I know men are so socialized from birth to not express their emotions. I work really hard to always try to say I hear you and I’m sorry you’re upset, rather than say calm down or any of those things that would silence him.”

6. BECOME ACTIVISTS ON MICRO AND MACRO LEVELS.

Julie Sissman was so passionate about gender roles at her daughters’ schools that she developed a workshop for teachers and camp staff, and has created a sample email that she encourages parents to send to schools and camps (see sidebar). In her workshops, she leads authority figures to reconsider their own biases and the ways they pass them on. Anyone teaching Jewish texts, or praying using traditional liturgy, or reading the Torah, encounters patriarchy, gendered God language, many more men named/talked about than women, very old-fashioned (understatement) rabbinic understandings of women’s bodies and gender norms, Sissman notes. “All of that is ‘in the air,’ and if schools aren’t naming it and asking critical questions about it, then it’s a real problem.” Ultimately, this is no different from other kinds of changes schools can adopt. Another example of micro-activism: “At my kids preschool, I asked the teachers: Why are all the dress-up clothes either princess or firefighter or cop?” she recalls. “The next year they got rid of all their play clothing and they put in big pieces of fabric and told the kids to create characters with these fabrics’.”

Getting into the habit of being an active parent at school will help when the big question emerges later on: sex education. Most schools fail miserably at this, and one of the major points Orenstein makes is that by abandoning sex-ed we are letting porn and sexist media educate our kids. Because sex makes us all squeamish, the fight for sex-ed is waged with much less fervor by parents like me than by conservatives who fight against it, leaving a vacuum.

Besides raising our own awareness and trying to change this national disgrace, we can change norms in our communities. Orenstein points to the Unitarian church as an example of a faith-based group that has its own sex-ed curriculum starting young, and notes that Jewish schools and camps should be doing the same. “We can make a profound difference,’ she says of Jewish groups. “We have this youth group culture—my whole life was youth group, religious school and camps. That can be leveraged.”

Some Jewish groups are doing a good job with this. At Moving Traditions, the teen groups for boys build up slowly to a discussion of masculinity and consent, with the goal, says Rabbi Tamara Cohen, of sending their graduates off to college to be active allies. “The goal is building a place, a space, a trusting, safe space where boys can really grapple with these ideas together,” she says.

Beyond our own communities, broader activism, whether it’s marching for abortion rights or a living wage, or writing letters to elected officials, is a way to model engagement while also building a better world for our kids.

7. WATCH OUR LANGUAGE, INCLUDING IN RITUALS.

“We don’t use boy/girl/man/woman and instead say kid, person, child. We have friends who are choosing to refer to their children using singular/they pronouns, and we are thinking about switching to that now that we’ve seen how relentlessly people gender children, even those in utero.” says Roberts. “Our child has long hair and is often referred to as ‘she’, and we don’t have a habit of correcting people because we want to model that there’s nothing wrong with being a ‘she’.”

In religious contexts, language matters too. “We have been using feminine God-language in our Shabbat practice,” says Cohen. “In a values and spiritual and religious level, ask what are the words we use, and why? And what are your assumptions about God and your assumptions about power?” Sissman agrees that bar and bat mitzvah prep are another chance to be “gender-critical” with kids using the same lens you might use to dissect themes in a TV show, for instance.

These kinds of lessons have an effect. “I remember when my son was seven and would be putting on plays for his cousins and would say ‘Ladies and gentlemen and people of all genders’” Cohen said.

All these principles connect with each other: to change our language, we have to revisit our own gender assumptions, reject a gender binary, and have vulnerable conversations. “I have the opportunity to talk to men who are coming to lead our groups, and it’s clear they’re in a process themselves,” says Cohen. “They are grappling with messages they received as children.”

And voicing unpopular opinions or using different language teaches our kids that resisting peer pressure or popular conceptions is okay, which will serve them well in the environments of intense masculine pressure that Orenstein describes.

We cannot turn the world upside down overnight; as parents in a society that is particularly cruel to families, we are often barely staying afloat in our daily lives. But Orenstein’s book reminds us that masculinity is a box that limits those within it, every day. We can’t entirely free ourselves, and our children, from the box, but we can begin to pry it open.