by Amy Stone

The New Documentary Featuring Golda Meir’s Off-the-Record Interview

At DOC NYC film festival —

“Golda” Meir – starring a long buried Israel TV interview

and how the film changed an Israeli Black Panther leader

by Amy Stone

My viewing companion came away from “Golda” visibly shaken, saying “Golda Meir was a hero. How could they show an off-the-record interview? Can’t they let her rest in peace?”

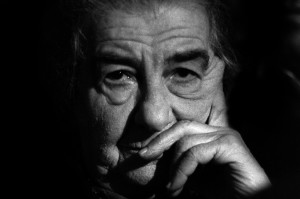

Photo Credit: Saar Yaakov GPO

The new documentary “Golda” – international premiere Nov. 10 at DOC NYC film festival– makes the conflict clear from the get go: Israel’s only woman prime minister (from 1969-74) changed the course of Middle East and global history. In America, she is known as the iconic grandmother of Israel. But in Israel she remains a controversial figure, excoriated for the loss of life in the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

What’s new is the never-before-seen footage of an off-the-record conversation with Golda, which took place following a 1978 Israel Television interview when the cameras kept rolling. Over numerous unfiltered cigarettes (Israel TV would not have shown images of her smoking), Golda Meir talked frankly. The two younger male journalists assured her the footage would not be aired.Co-director of this documentary Shani Rozanes says the interview was discovered accidentally in the archives. The 40-year statute of limitations protecting it from public viewing had expired. The black and white footage is the scaffolding of the film – the point of departure to historic footage and interviews with the silver-haired old guard close to her or opposed to her and two women with perspectives on Meir as a woman ruling a 10-man cabinet. After all these years, they are passionate, they are thoughtful, they are honest.

Directed by Sagi Bornstein, Udi Nir and Shani Rozanes, the German-Israeli production in Hebrew with English subtitles weaves together wide-ranging interviews, including with Golda’s longtime nemesis Uri Avneri; journalist and Knesset member; Zvi Zamir, who was Mossad director 1968-74; Meron Medzini, Golda’s spokesman from 1969-74; Reuven Abergel, Israeli Black Panthers co-founder; and devoted grandson Gideon Meir.

Golda Meir came to power suddenly, following the fatal heart attack of Prime Minister Levi Eshkol in 1969. She fell from power almost as suddenly following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Egypt and Syria rolled in on the totally unprepared Israeli armed forces. In between she led a country still largely enraptured with the stunning victory of the 1967 Six-Day War. She dealt with an occupied population in territory tripling the size of Israel; the massacre of the Israeli Olympic team in Munich in 1972; the start of Jewish settlement in the West Bank; and the Israeli Black Panthers’ demands of equality for Israel’s Mizrahi Jews.

In her laced-up oxfords and pocketbook over her arm, she was an old 71 when she became prime minister. (Compare Nancy Pelosi, now 79.) Her socialist Zionist ideology had been molded in her youth, a Ukrainian immigrant from Kiev growing up in Milwaukee. She remembers her father telling her, “Men don’t like smart girls” when she wanted to continue her education.

She defied her family and left to build the Jewish State. As the world changed, her views remained static. In the Israel Television interview, she laments that Israel has changed. Israeli women take their cues from America’s cultural fads with mini or micro-mini skirts. Money’s an ideal. Golda Meir never deviated from the ideological values of the good old pioneering days when Ashkenazi immigrants built the Jewish dream.

Feminists have faulted Golda for failing to champion other women. Colette Avital, long-time diplomat and Knesset member, recounts meeting her in Boston for eye surgery in 1977 and being “insulted, berated” when she told the former prime minister that Sadat was coming to Israel. Henriette Dahan Kalev, founder of the Gender Studies Program at Ben Gurion University and a founder of the Mizrahi feminist movement, suggests, “Perhaps she blurred her sexuality and opted for the more masculine look so she’d be taken more seriously.” Who knows if a cabinet of women could have saved Israel from the Yom Kippur War? Golda Meir spoke of her fears of an attack to general Moshe Dayan, her minister of defense, who assured her Israel had nothing to fear. There was not a single voice of warning in her cabinet.As those close to her testify, she could be loving, she could be cruel, and she was tough. She truly believed “ein breira” (“no choice”), saying, “My conscience is clear. Every Arab in the world has a choice. A Jew has no choice.”

She refused to negotiate with any Arab leader without face-to-face talks. Her successor, Menachem Begin, got to meet with Egypt’s Anwar Sadat on Israeli soil and they jointly collected a Nobel Peace Prize, but Sadat paid for the visit with his life. Harking back to when Gamal Abdel Nasser was in power, Golda Meir’s sister, Clara Stern, remembers suggesting Golda try to put herself in Nasser’s shoes. “She looked at me as if I was crazy.”

That refusal to empathize seems profound, even as Golda said, quite poignantly, “I can never finish a dream.” She meant it literally. As prime minister during the War of Attrition following the Six-Day War, she insisted on being phoned at any hour of the night to be told of an Israeli soldier’s death. Interviewed in “Golda,” the devoted head of Mossad, who did unspeakable deeds to wipe out terrorists worldwide after the Munich massacre, wondered, “How did this woman who was clueless about operational issues make all those decisions with her common sense, with her faith in the Israeli people, in the State of Israel? That’s what she lived for.”

Meir embodied a Zionist ideology that built the Land of Israel blind to the Arabs in that land. She seemed equally blind to the systemic second-rate treatment of Israel’s Mizrahi Jews. Her meeting with five Israeli Black Panthers was painfully dismissive. They had come prepared with statistics but she refused to listen. Her Zionist ideology seemed to prescribe that all Israelis develop into Ashkenazi pioneers.

Her longtime spokesman blames himself for the failure to prepare Meir for the meeting, saying, “We assumed she’d understand.” Certainly the inferior status of “Eastern” Jews in Israel was no secret. While I was living in Israel before, during and after the Yom Kippur War, I took a course on “Inequality in Israel” for overseas students at the Hebrew University. It was obvious: Ashkenazi Jews were on top; Mizrahi Jews second class; Arabs on the bottom. Golda Meir embodied that truth. Tragically, Meir didn’t understand how as a champion of socialism she’d become a symbol of the detached racist. In fact, following the Black Panthers meeting with her, and riots in Jerusalem, the film notes that Golda Meir’s 1972 budget had more money for housing, education and welfare than any previous budget.

Seeing her direct gaze in living black and white, hearing her speak, it is hard to escape the power of her personality and convictions. They come through loud and clear in the off-the-record Israel conversation. Slumped in her chair, she still remains intense, charismatic, witty, ready to take on her questioners.

“Golda” closes with her response to what she’d like the title of her chapter in history to be. She answers, “I hope whoever writes about me, I hope he’ll write about me with mercy.”

This film does it.

“Golda” ripples – The film is getting a wide viewing in Israel. Most remarkable, Israeli Black Panthers Reuven Abargel writing in Haaretz on June 29th, 2019. Excerpt translated by “Golda” co-producer Udi Nir:

Only after watching the film about Golda Meir, I could, for the first time, get to know the story of her life.

“Golda,” getting into the details of her life, pushed everything aside, made me forget the unpleasant hours I spent in her office back then. My heart ached when she spoke of her deprived childhood in Russia, with her mother and sister, after her father left them for the U.S. When she spoke of the empty stomach, harsh conditions, and persecutions by the gentiles.

As the film progressed, I saw an ill woman [she suffered from cancer], going through painful medical procedures with very little time to sleep. I saw how she carries on her small shoulders the corrupted Mapai Party, the sectorial sectarian protests, the Yom Kippur War, the War of attrition and the Agranat Commission [on the Israel Defense Force failings before the Yom Kippur War].

I watched and asked myself how a fragile, sick woman, with childhood traumas, manages to push this broken wagon, with all the generals around her undermining her. Suddenly she seemed alone in the field, with a pack of wolves surrounding her, lurking in wait for the prey. Towards the end of the film I told myself that if I knew then, when I met her for three hours, what I see now in this film – that meeting would have looked completely different.

“Golda” made clear to me that difference between the Ashkenazi and Mizrahi cultures, and the prism of all the Mapai leaders. Amongst them all, Golda Meir was the most human. If she would stand next to me after the film ended, I would have approached her, congratulated her and wished her good health. After all, we are all human beings.

“Golda” international premiere at DOC NYC, Sunday, Nov. 10 at 2:05 pm, SVA Theatre. And a shout-out to go2films, the almost all-woman Israeli film distribution company headed by Hedva Goldschmidt, mother of five.

In 14 years in business, they’ve given birth to a total of 12 babies (winning a certification from Israel’s Jobs for Moms). Goldschmidt says, “We have one man in the office [of eight], who suffers quietly. But he has many sisters so he manages.”

At DOC NYC I’ll also be watching:

“Kosher Beach” with director Karin Kainer in person at the international premiere. Looking at the importance of this Tel Aviv “modesty beach” to the Orthodox women and girls of Bnei Brak who defy rabbis fearful of the beach’s “immorality.” (Israel, 62 min, Hebrew). Wednesday, Nov. 13, at 5:05 p.m. / IFC Center

“Healing From Hate: Battle for the Soul of a Nation” with director Peter Hutchison at world premiere. Profiles Life After Hate, an organization founded by former skinheads and neo-Nazis that supports white nationalists seeking to break away from these radical movements. Given exclusive access, director Peter Hutchison follows group counselors as they attempt to reform individuals and offer support to communities impacted by the rise of hate activity. “Healing from Hate” explores the root causes of radicalization and what it will take to return us to a more tolerant world. (USA, 85 min). Wednesday, Nov. 13, at 7:15 p.m. / Cinepolis Chelsea

Amy Stone is a contributing editor and a founding mother of Lilith.