by admin

Golda Meir and Israeli Leadership

Golda Meir, a political symbol for so many women, has received little serious attention in the country she helped found. For many Israelis, she is simply uninteresting. For some, she remains the embodiment of a socially insensitive, practically exclusive, and eventually incompetent political establishment. And for others, she will forever be the face behind the debacle of 1973 and the reverberating voice of intransigence in efforts to achieve a just and lasting peace between Israel and its neighbors. In popular lore, she is still perceived as one of the weakest, if not the worst, of Israel’s premiers.

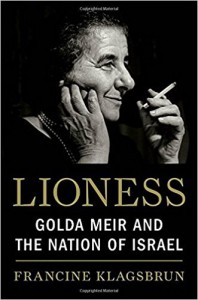

All these images are simplistic beyond words. A new biography, Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel (Schocken, $40), by Francine Klagsbrun, is by far the most comprehensive, best-researched and carefully nuanced study of Israel’s fourth prime minister published to date. Klagsbrun sets out to portray Golda—warts and all—and to try to understand her role in the establishment and shaping of the State of Israel during its formative years. Those who delve into this massive volume (over 800 pages) cannot remain indifferent: it forces even the most skeptical and opinionated—almost 40 years after her death in Jerusalem in late 1978 and 120 years after her birth in Kiev, Russia, in May, 1898—to reassess the Golda legacy and reexamine her impact on Israel’s trajectory.

All these images are simplistic beyond words. A new biography, Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel (Schocken, $40), by Francine Klagsbrun, is by far the most comprehensive, best-researched and carefully nuanced study of Israel’s fourth prime minister published to date. Klagsbrun sets out to portray Golda—warts and all—and to try to understand her role in the establishment and shaping of the State of Israel during its formative years. Those who delve into this massive volume (over 800 pages) cannot remain indifferent: it forces even the most skeptical and opinionated—almost 40 years after her death in Jerusalem in late 1978 and 120 years after her birth in Kiev, Russia, in May, 1898—to reassess the Golda legacy and reexamine her impact on Israel’s trajectory.

The Golda Meyerson/Meir (she Hebraized her name at Ben-Gurion’s insistence only in 1956, when she became Foreign Minister) who emerges from this biography is a bundle of contradictions. She was, since her childhood, fiercely independent yet consistently dependent on friends and family. She was warm and vindictive; pragmatic and stubborn; shrewd and a team player; courageous and unsure of herself; sarcastic and embracing; charismatic and studiously frumpy; full of stamina and constantly ill; a workaholic who nevertheless found time for countless romantic relations (a topic which receives perhaps too much attention in what is a political biography); calculating and instinctive; motherly to all but an absent mother to her children. Golda, who was both manipulative and autocratic, was also a generous friend. Each of these traits helps to account for various features of her public persona.

Klagsbrun repeatedly underlines Golda’s ambivalence as a woman leader. Although she suffered repeatedly, to her dying day and beyond, from latent and overt sexism, she bristled at the mere thought of being a leader of women—even when her first steps in pre-state politics were taken within the framework of women’s organizations. She squabbled repeatedly with other strong women—from Ada Maimon and Manya Shohat to Beba Idelson and Shulamit Aloni—and though surrounded by women assistants who were also close friends (Lou Kedar, Regina Medzini), she made no attempt to promote women and went out of her way to deride feminists and feminism. She was, even at her political pinnacle, the ultimate queen bee.

Golda Meir, the indefatigable spokesperson for the creation of the State of Israel and its most consistent and passionate defender during its early years, was first and foremost an integral part of the establishment who nevertheless remained a perennial outsider. She came to Palestine from the United States and was not part of the pioneering Eastern European nexus that controlled the Yishuv during the British mandate. Her Hebrew was scrappy at best, and she never fit into the intellectual Zionist elite to which she wanted so much to belong. She worked her way into the Histadrut and then into the inner circles of Mapai (the forerunner of the Labor Party) by a mixture of determination, hard work and fundraising capabilities. And when she succeeded in reaching positions of influence, she was nevertheless never considered an integral part of the founding elite. (She was a signatory of Israel’s Declaration of Independence only by chance, as she happened to be in Tel Aviv when one of the intended signers got stuck in Jerusalem on May 14, 1948).

Golda always knew, however, when to serve the party and how to ingratiate herself with those in power at any given juncture. This is how she became Minister of Labor, then Minister for Foreign Affairs and, under Levi Eshkol’s premiership, Secretary-General of the Party—the maker and breaker of political careers (although she never really developed her own political base). At each step, lacking the raw ambition of many of her male counterparts, she never refused to accept new positions in order to carry out “the will of the party.” This attitude brought her in 1969 to the Prime Minister’s office. It also contributed to her demise: she became the personification of the establishment even when she spent most of her years at the far margins of the elite.

This is perhaps why some of her most notable achievements have been obscured over the years. Domestically, she was critical of how the country absorbed the first waves of mass immigration and was an unrelenting proponent for liberating Soviet Jewry. She was central to the creation of new jobs and to laying the foundations for Israel’s advanced welfare state. Externally, she not only opened Israel to the newly independent countries of Asia and Africa in the late 1950s, but she consistently fostered relations with the United States in general and with American Jewry in particular. She guided the establishment of the special relationship with the United States and fought for the reinforcement of these ties despite efforts by her nemesis, Shimon Peres, to favor the French connection. And as Prime Minister, Golda Meir was directly responsible for securing the American arms convoy that allowed the country to prevail in the Yom Kippur war.

This record, ironically, also contributed to her downfall. Despite her close relations with Jordan’s King Abdullah, and then with King Hussein, she never really saw fit to reach out to Israel’s Arab neighbors nor to initiate serious overtures on the Palestinian front. She exhibited an overreliance on her military advisers (including the popular Moshe Dayan), to the point of ignoring her instincts both on the probability and on the timing of an Egyptian-Syrian assault in 1973. Although her conduct during that war was cool and collected, she failed to understand that in its aftermath Israel would never be the same. The social, economic and religious tensions she had neglected, coupled with her inability to sketch out a workable diplomatic horizon, proved her comeuppance. The old establishment could not sustain itself in these circumstances and she became its first, and most convenient, victim.

Was Golda Meir a formidable leader or was she an unusually dominant political practitioner? Did her commitment to the Zionist cause contain an enduring vision? Why is her international reputation far more lasting than her impact at home? The first step in addressing some of these questions is to delve into Francine Klagsbrun’s fascinating biography and learn about the enigmatic facets of the complex person who was unquestionably a lioness and the keeper of her cubs, but not necessarily the leader of the lions.

Naomi Chazan is professor emerita of political science at the Hebrew University and co-director of Shavot (the Center for the Advancement of Women at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute). She was a member of the Knesset (Meretz party) and president of the New Israel Fund, where she now serves on its board of directors.