by Patricia Grossman

Meet the Heroes Who Performed 11,000 Abortions Before Roe v. Wade

In the four years before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, the Chicago-based service collective known as Jane performed 11,000 abortions. At first Jane enlisted doctors to perform the procedure, but when the collective of women found out their chief practitioner was not a doctor after all, a subset of Jane learned to perform abortions themselves, including inducing miscarriages in women with later term pregnancies. The story of Jane—how it was organized, how it evolved, and the lives it changed—is a fascinating document of a vital movement in the history of women’s rights.

In the four years before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, the Chicago-based service collective known as Jane performed 11,000 abortions. At first Jane enlisted doctors to perform the procedure, but when the collective of women found out their chief practitioner was not a doctor after all, a subset of Jane learned to perform abortions themselves, including inducing miscarriages in women with later term pregnancies. The story of Jane—how it was organized, how it evolved, and the lives it changed—is a fascinating document of a vital movement in the history of women’s rights.

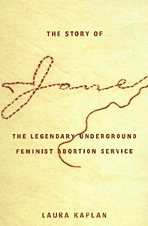

Twenty years ago, the paperback edition of The Story of Jane, by Laura Kaplan, was published. Since then, Roe v. Wade has been assaulted at all levels of government, and the book is increasingly relevant to our times.

PATRICIA GROSSMAN: When Jane first formed, how aware were its members about women’s health issues?

Laura Kaplan: Because we had been powerless, we knew nothing. When we started Jane, there weren’t any self-help books. You couldn’t go into a bookstore and get a book about women’s health. We were barred from this information. And not only were we barred from this information about our own bodies and how they worked, but were given the message that wanting to understand was somehow creepy and unseemly. Our bodies were the purview of men, including doctors, and the doctors were pretty much all men then.

PG: Many readers might be surprised to learn about the early participation of the Baptist Church in the abortion movement. Can you talk about that?

LK: This is something I always try to emphasize when I talk to young people, especially because people these days think there’s the religious anti-abortion view, and then there’s the women’s point of view. But in fact churches—not the Catholic Church of course—but other denominations and Jewish organizations were very, very involved in the early abortion work. There was a Baptist minister at Judson Memorial Church in NYC, Howard Moody, who organized the first Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion in 1967. He got a bunch of clergy—men again—involved in helping women and he found doctors through their various congregations who were sympathetic and willing to perform abortions. The clergy was in a unique position; they could do the referrals, but they could also take a very public role because they had the moral authority of the [faith institution] on their side.

PG: Why do you think the clergy were there so early in the movement?

LK: They heard first-hand. Most of us didn’t know much about abortion, but the frontline people did—doctors, police, and clergy. They heard the stories and really knew what was going on in women’s lives. The clergy was pretty savvy about knowing they were putting women in a difficult position, talking about something that was so fraught with guilt and self-blame.

PG: What was the clergy’s involvement with Jane?

LK: We knew each other. So when I asked the minister of the Chicago Clergy Consultation Service if he ever referred to us, he laughed and said, “Well, I have to admit that in a few cases when the woman had absolutely no money, yeah, then I had to send her to Jane because who else was going to do it for free?”

PG: Jane was an illegal group, and yet if you didn’t find a way to publicize your services you couldn’t help women. How did you deal with this Catch-22?

LK: We worked in different places all the time because we had to. We were always walking a fine line. [If we were] being too underground, people couldn’t find us. And, of course, we couldn’t screen women to find out who could’ve been a plant coming through. And there was suspicion that members of the group were plants. Who knows.

PG: Throughout the book you stress the equal partnership between Jane and the women it served. Can you talk about why that was so necessary?

LK: It wasn’t really an equal partnership. We wanted it to be. We would say to them, we’re doing this with you, not to you. To ourselves, we talked about women coming through Jane, not to Jane. It was a process, not a place or an action.

PG: A few years in, Jane was busted and several members were arrested. What about the women you were serving that day?

LK: None of them would testify against us. So in terms of building that sense of “we’re in this together,” I may be jaundiced and say, “oh, yeah, we thought we were doing this [together].” But in fact, if you look at it, we really did build a sense of community. When word about us spread in the black community, on the south side and west side—and in the later days that’s where a majority of the women we saw came from—the word was, “it’s a women’s group, they’re not in it for the money, you can trust them.” Remember, these were hippie years so the younger ones of us in the group looked like hippies and lived in neighborhoods these women didn’t live in and never went to. Chicago’s a pretty segregated town. And those of us in the group lived fairly sheltered lives. We were primarily white, middle class women who’d gone to college.

PG: Many black women seeking an abortion at the time were accused by Black Nationalists of being traitors to their race, of participating in racial genocide. This must have been a real bind for Jane.

LK: Our whole focus, from the beginning to the end, was on the individual woman who contacted us and what her needs were. So the boys could talk any way they wanted to. They weren’t speaking for black women. Black women had other needs, and as long as we were constantly focused on the need of the individual woman who contacted us, regardless of her class, race, age, marital status, anything—then we felt okay about what we were doing. We knew that boys were going to say what boys say. And it’s still the case today—still the denigration of what women want and what women need.

Because we were underground, and we were illegal, the women who came to us were desperate. Why would they trust a bunch of white young women with their lives unless they were desperate? If women were desperate to end their pregnancy, they didn’t care what anyone was saying into a bullhorn because they were going to live their lives and they were going to be the ones to take care of that child.

PG: Did the women you serve ever come into the light?

LK: While I was working on the book there was some Supreme Court decision that was the beginning of the hammer coming down, and shortly afterwards the feminist bookstore in Chicago—Women and Children First— asked two of the central people from Jane to come and talk about the service. Ruth and Jody did this talk and I remember them telling me it was SRO (standing room only), packed with young women who wanted to know everything, exactly how you do this, should we do it again. And there was an article in The Chicago Tribune that stated, “Illegal abortion group says they’ll do it again,” which Ruth and Jody did not say. Sometime after that the reporter got a letter from a woman in California saying, “I was one of those 11,000 women. I was a young black woman in college; there was no way I was going to have a baby. They changed my life and taught me what it was to be a feminist. And now I have a three-year old daughter, and I can teach her what it means to be a feminist because of my experience with Jane.”

PG: How close do you think we are to needing Jane again?

LK: The landscape is different on so many fronts. The thing to remember about [then] is that there was no anti-abortion movement simply because abortions were underground. The average person didn’t know they were going on. So there weren’t the threats that people are now facing of losing their life because of what they do. But more importantly the technology has changed so much. Nobody needs to be doing D&Cs anymore. There are medical abortions that are really simple and easy and there are groups around the world, in places where abortions are illegal that are already doing this. They are counseling women, providing medication, doing follow-up, preparing them for what they’re going to experience in just the way we did and for just the same reasons, and I know that that will happen here as well. What some people in robes or statehouses do is not going to change—it never has changed—what women see as what they need to do. I hope that Jane, if anything, gives young women the courage to know that they can do what needs to be done, that it has been done before, on a small scale, but it definitely can be done again, in a very different way—in a much easier way.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.