by Oksana Mironova

Soviet Daughter: An Interview with Julia Alekseyeva

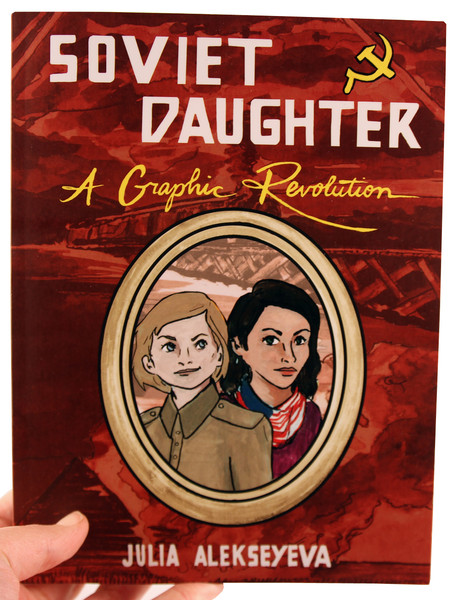

Julia Alekseyeva’s memoir-cum-history, Soviet Daughter, chronicles major events—including the Russian Civil War, the Revolution, and World War II—through the eyes of her rebellious, Jewish great-grandmother, Lola, who was born in 1910. Lola would become a secretary for the NKVD (later the KGB) and a Lieutenant in the Red Army. Towards the end of her life she began to write down her story in a memoir that contained a note at the front specifying that it should not be read until after her death, which is when her great-grand daughter first saw Lola’s writings.

Julia Alekseyeva’s memoir-cum-history, Soviet Daughter, chronicles major events—including the Russian Civil War, the Revolution, and World War II—through the eyes of her rebellious, Jewish great-grandmother, Lola, who was born in 1910. Lola would become a secretary for the NKVD (later the KGB) and a Lieutenant in the Red Army. Towards the end of her life she began to write down her story in a memoir that contained a note at the front specifying that it should not be read until after her death, which is when her great-grand daughter first saw Lola’s writings.

Alekseyeva, who immigrated to Chicago with her family in 1992, weaves her own story into this narrative, describing her experience with immigration, assimilation into American culture, and radical politics. Today, she lives in Brooklyn, teaches Japanese cinema and documentary film at Brooklyn College, and is a Ph.D. candidate in Comparative Literature at Harvard.

I met up with Julia in downtown Manhattan, after a Jewish solidarity rally for refugees in Battery Park. We talked about Russian history, Soviet feminism, intergenerational friendships, and the importance of immigrant literature in the current political context.

Oksana Mironova: One of the things that I enjoyed about your book was the portrayal of everyday life in Russia. Was your intention to humanize Russian history for an American audience?

Julia Alekseyeva: That was one of the main purposes of the book. I noticed that many Americans were not familiar with what everyday life was like in the Soviet Union. My family’s experience was different from the standard Baby Boomer understanding of what life was like there: everyone standing around in line waiting for toilet paper, while there is constant terror in the street.

Most Soviets were unaware of the extent of political repression or the details of what was happening in the Gulags, which is not that different from the reality of most Americans today.

Further, after the Stalinist period, there were decades in Soviet history that were fairly peaceful. I was trying to push back against a conception of the Soviet Union as a unilaterally dark place.

OM: Have you gotten any feedback from readers reacting to this more nuanced portrait of Soviet history?

JA: Most of the feedback so far has been from readers with a connection to the former Soviet Union or even immigrants from other countries, reflecting on their family members’ experiences. I get a couple of Facebook messages a day that say, “My great-grandmother went through the same thing,” or “My uncle went through the same thing.”

I have gotten a couple of responses from readers who were interested in the history, but were confused by the book culminating with an activist message. These are readers who have a very stark and negative view of communism… these responses were less critical and more interested in knowing why my biographical narrative culminates in an interest in leftist politics.

OM: Why is your book a graphic memoir novel, instead of just a novel?

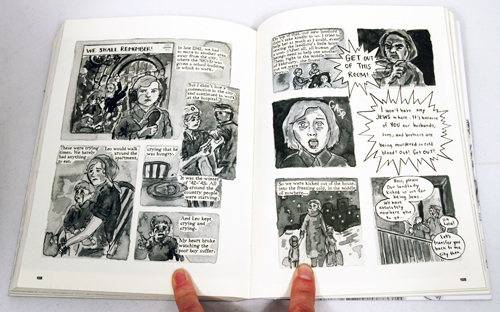

JA: Partially, it is because I like to draw… However, it is also because Soviet culture was very visual. I wanted to make Soviet Daughter a full, encompassing story, where the reader can see what my great-grandmother was seeing.

JA: Partially, it is because I like to draw… However, it is also because Soviet culture was very visual. I wanted to make Soviet Daughter a full, encompassing story, where the reader can see what my great-grandmother was seeing.

I started the novel in Chicago, and would go to the Harold Washington library almost every day to look at early Soviet history books. I completed the book in New York, and would visit the Central Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library to look at both Soviet texts and images. In particular, I watched a lot of 20s and 30s Soviet films, as wells films from the 60s and 70s that re-envisioned the early Soviet period, taking lots of screen-grabs as references for my drawings. I also researched such period details as how long the skirts were. Since my main reference point, my great-grandmother’s memoir, was not visual, I wanted to show what she was seeing and what she looked like.

OM: There is an established field of post-Soviet, Jewish immigrant writers like Lara Vapnyyar, Gary Shteyngart, Yelena Akhtiorskaya, Boris Fishman, David Bezmozgis, and Anya Von Bremzen. Did you use any post-Soviet memoir or fiction as reference points when you were drawing/writing your novel?

JA: There is a range of how people from the former Soviet Union write about their experience, and I push back against writing that is viciously pro-American and anti-Soviet. I like writers like Gary Shteyngart, whose work is a lot more ambivalent about the United States. And, it was great to see him speak at the rally, just now!

If anything, the great classics, like Tolstoy and Hugo, influenced my work more than anything else.

OM: Does Soviet Daughter fit into this growing post-Soviet Jewish field?

JA: When I started working on the book, I got in contact with a couple of people associated with writing and publishing, and the bulk were skeptical of sincerity in literature. Their criticism was that it was not satirical enough…but it was not what I wanted to do; I wanted the opposite – radical sincerity. And, perhaps this is partially a generational thing, but I don’t want to make everything about age exclusively.

OM: That was part of the reason why I enjoyed the book so much. Coming from a place where I am not immersed in fiction, I find that criticism or messaging in satirical writing is easy to push aside and ignore.

JA: It is easier, and it is comforting to enshroud yourself in dark humor. And that is still a reaction I get from academics too, especially of Russian and Jewish heritage… there is an earlier set of thinkers that were comforted by irony and distrustful of a sincere voice.

OM: In Soviet Daughter, you describe the depth of your friendship with Lola, your great-grandmother. Are inter-generational relationships stronger in post-Soviet communities and among immigrants in general?

JA: I came to the U.S. when I was four, and grew up immersed in American culture, becoming an American. This was hard for my parents to accept, because they felt a strong bond to the culture and values of the place they left, at the time that they left. The belief system that I developed was so much closer to my great-grandmother’s than to anyone else’s in my family. The early idealism of the Soviet period to me felt almost American; it was dissenting and critical, in contrast to the fearful reaction to the world of the middle generations, probably a reaction to the trauma of the Stalinist period. I don’t remember my great-grandmother ever being afraid of anything… She was a badass.

OM: It also seems like your great-grandmother was more socially liberal than her daughter and granddaughter. Did she ever describe herself as a feminist?

JA: That was one of the reasons why I stuck so close to my grandmother. She lived her life in a feminist way, avant la lettre, even though she never wrote or talked it about. She had two husbands; after her second husband was killed in World War II, she made the decision that she could stand on her on two feet, without the support of a man. She had a strong sense of what she wanted, and thought she was capable of doing everything herself…which she was.

During the Stalinist period, there was a lot of agitation for the importance of the nuclear family, which resulted in more conservative values. There was a part of my book I had to cut, where I am having an argument with my mom and she says that no one will love me because I can’t clean the apartment properly. The accompanying drawing has my great-grandmother looking at my mom in a huff. My great-grandmother was a contrast to the broader cultural idea in many post-Soviet households that women must be docile and men must be strong. She was a strong counter-role model for me growing up, going against this almost 1950s American housewife archetype.

OM: How does your Jewish identity compare and relate to your great-grandmother’s?

JA: My Jewish identity is pretty much the same as my great-grandmother’s–as a communist, she considered herself an atheist, and I’ve been an atheist for as long as I could remember. But for us, as for many Soviet families, Judaism was less of a religion and more of an ethnic identity. Some sources label Judaism as an “ethnoreligious identity.” I find that my American Jewish friends often ignore the “ethnic” part!

The only difference between my Jewish identity and Lola’s Jewish identity was that she grew up speaking Russian, Ukrainian, and Yiddish, and was immersed in Jewish culture and tradition. Since my family avoided anything remotely religious (even the cultural aspects), I had to learn about Jewish culture later on in life. I didn’t even try matzo ball soup until I was 18! My half-Jewish partner knows infinitely more about religious practice than I do. But, I always felt that the cultural aspects of Judaism are a part of my identity, and I’m continuing to explore them.

OM: Did your great-grandmother have any thoughts about the United States?

JA: In her memoir, she did not like the U.S. at all when she got here. It took her a while to get comfortable. But in the process of becoming a part of a collective again, when she moved into a subsidized housing development for senior citizens, she started to thrive. She organized events for other residents and felt like she had a purpose and a community.

However, she never really talked about American politics. Russian-Americans are inundated by Russian news [which tends to be very conservative], and she didn’t watch that much of it. Instead, she preferred to read, retreating into her intellect. I appreciated that because in Chicago, the Republican party would send representatives to the senior citizens’ homes, to convince Russian immigrants to vote Republican. By ignoring the Russian media, she was more open minded… During the 2008 election, after we had a number of conversations, she voted for Obama.

OM:Today, we are in a very different political context. How do you think the meaning and perception of your novel changes in light of the current administration’s relationship with the Russian government and assault on refugees and immigrants’ rights?

JA: As I was finishing writing the book, the war between Russia and Ukraine escalated and pro-Russian fighters shot down the Malaysian Airlines airplane over Ukraine. Suddenly, it became even more important for me to finish the book.

Given the current political environment, I am planning on writing another 32 pages to contextualize everything in the book. Going to rallies, including the one we just came from and the D.C. Women’s March, there are a lot of signs that blur together Putin, Trump, and the Soviet Union, which misses the complexity of Soviet and Russian history. Communism = Russia = Bad is not a productive way of thinking. Trump is certainly not a communist… if only!

If you look at what many individual people were striving for in the early days in the Soviet Union, it was inclusion and liberation, which is of course not what Russia stands for now.

In making a graphic novel, I wanted the readers to walk away with a visceral understanding of what life was like in the Soviet Union. At this moment in history, it is important to understand ambivalence. The more we bring to the forefront individual experiences in places that are not familiar to most Americans, the more people will be open to understanding worlds that are very different from theirs and also in engaging with ambivalence.

Oksana Mironova was born in the former Soviet Union and grew up in Coney Island, Brooklyn. She is the founding board member of the NYC Real Estate Investment Cooperative and writes about cities, alternative economies, and public space.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.