by admin

Remnants

Art: Michal Machmany, michalnachmanyart.com.

My mother was diabetic. Diabetes is a disease of famine in the midst of plenty; an inability to derive nourishment from abundance.

Our family’s brick row house in Queens, New York, to which we had immigrated in 1956, had an efficiency kitchen with dark, walnut-stained cabinets, a beige Formica countertop, and an extra-large avocado green double-door refrigerator packed to overflowing. You had to take something out before you could put anything in. Jars in stacks, piles of leftovers in assorted containers. Potato salad, coleslaw, mustards, pickles, sauerkraut, deli meats, butter, cheeses, milk, buttermilk, heavy cream, sour cream. Brisket from the takeout restaurant, orange juice, eggs, jams, jellies, mayonnaise, ketchup, cookies, cake, cough syrups, old medications, insulin, needles, Jell-O, prunes. Lots of prunes.

I never brought my friends home. I was ashamed of my mother because she was so fat. She was always on a diet, clipping newspaper articles newspaper articles with low-fat recipes and miraculous weight loss programs. Between her sluggish thyroid, low insulin, and Polish cooking, she didn’t have a chance. I couldn’t stand to watch her eat.

One day, when I was a teenager, I mentioned to my mother that if she really wanted to lose weight, she should just eat less.

She then told me the first of many fragments of her life during the war. There was no food. Everyone was always hungry. She had a ration card that entitled her to one roll per day. The dough was made with flour and sawdust. She didn’t want to eat the whole thing at once so she found a book and cut out a hole in the middle of the book. She ate half of the roll in the morning and she put the other half in the book to eat later. One night she opened the book and found a mouse had eaten all the bread. The following morning, she ate the whole roll.

After that, whenever I saw her eating, I would say to her in my mind: Eat…eat all you want.

Using the same heavy knives and forks my parents brought with them from German-occupied Poland, we ate with the war every day.

Survivors of the holocaust tend to fall into two categories: Those who can’t stop talking, and those who never talk about the war. I knew that I had been born in a displaced persons camp in Austria, but I was unaware of the details of my birth. (Years ago, in a “re-birthing” workshop, on the floor, in a fetal position, I regressed in time till I “saw” myself in a large room filled with rows of beds and the sound of people crying, whimpering and moaning, and me, all alone. No one wanted to be there, and no one wanted me.) My mother told me that a year before I was born she had a miscarriage in her fifth month of pregnancy. According to her, my father cried for days, but she was not upset about it because, she said, “I didn’t need a noose around my neck.”

And who could blame her?

For five war years she lived daily with ceaseless, gnawing hunger and the fear her false identity would be discovered, all the while grieving the loss of her beloved parents, her brothers and sisters, and her career. She had been a concert pianist in Poland, and music had been her life.

Although both my parents were Polish, they came from completely different worlds. My father was 20 and my mother 32 when they met. My mother came from a thriving, middle class Jewish shtetl enlivened with culture and music. Everyone in her family played at least one musical instrument. She spoke several languages and was on a career path to be a concert pianist. My father at 17 had been taken off his family farm in rural central Poland by the Germans and put to work as a slave laborer. He was exceptionally gifted as a mechanic and could repair cars, wringer washing machines, toasters, blenders, and even our old tube television. My mother read the New York Times, my father the Daily News.

My father got a job as the night-shift busboy at a New York restaurant. We lived a frugal life, yet the first piece of furniture they bought in America was a piano. My mother dreamed that I too would be a concert pianist. I remember having to sit at the piano, feet dangling, my little fingers struggling to span the chords, and my mother’s voice yelling from the kitchen, “Play it again!” She taught me the way she had been taught with a ruler, smack on the fingers.

I grew to hate the piano. For many years, I couldn’t stand to hear her play. Chopin, that anti-Semite, Rachmaninoff, the Romantics. I would go up to my room and put toilet paper in my ears.

My mother wore her hair in a particular late 40’s style. Long bangs curled over a wire mesh form shaped like a cannoli. In my recurring childhood dream that roll of dark hair would turn into a locomotive train and run me over.

When I was an adult, living away from my parents, my drive down to New York to see them always took longer than the drive back up to Boston.

I began this monthly ritual after my dad, at 72, had quadruple bypass surgery, and my parents stopped driving up to visit me. My mother, 12 years older than my dad, had never learned to drive, and she was afraid of flying. So it was up to me to visit them.

For several years, the visits followed the same pattern. Filled with anticipation, I would pack up the car and set off. The tedium of the five-hour drive would be occupied with rehearsing the questions I would ask: Where were you born? What were your parents like? What were their names—your brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, who loved you? Whom did you love? What were your days like? Where did you live? Tell me your dreams.

I needed answers. Time was running out.

As I pull into the driveway in the back of the brick row house, I am so grateful that my parents are still alive and that they can still answer my questions. Only a month has gone by, but I wonder how much they have aged. Will they look the same?

In the summer, the garden next to the driveway is filled with giant tomatoes, cucumbers, dill, parsley, string beans, a peach tree, green peppers, radishes, and sunflowers six feet high. Along the chain-link fence are gladiolas, peonies, dahlias, and zinnias, with impatiens for ground cover. The shaded patio is filled with huge oleander bushes, heavy with pink flowers. My father has been propagating oleanders for 40 years; everyone in the neighborhood has one of his bushes. Once, on a visit to my aunt Evelyn in Vancouver, I spotted in her window the huge oleander that my father had given her 20 years before. Since it was winter, she had decorated hers with white tissue-paper flowers wired onto the stems.

My parents are waiting for my arrival. They sit on webbed aluminum folding chairs, which qualify as antiques. When the webbing breaks, my dad effortlessly weaves in a replacement band to match the existing pattern. The rusted chairs are tied to the patio railing with old clothesline so they won’t blow away. When one finally gives way, several hours are spent comparison-shopping before we head for Home Depot to buy a new one for $12.99.

They smile when they see me. Hugs and kisses all around. I am so happy to see them. “How was the drive? How long did it take? Did you eat something? Good you are safe.” I walk in, put my bag down, walk over to the refrigerator, open the door, and stand there for a while. In my house, with the exception of a few condiments and beverages, the refrigerator is empty. This refrigerator, as always, is overflowing.

My father makes me a sandwich; my mother ladles out chicken soup. We eat.

I remember, again, that they lived in a state of famine for years. We catch up on neighborhood gossip, but they never ask me what I am doing up in Boston, never inquire what my life is like. They don’t know what to ask. Compared to them, compared to their suffering, I am insignificant, almost invisible. They go off to take naps, and I sit alone at the table, forgetting what it was that I wanted to ask them. I look around, memorizing the details of their surroundings here.

Their house is modest, distinguished in the front from the others on the block by a verdant square of green lawn backed by an astonishing array of azaleas, rhododendrons, pansies, lilies of the valley, peonies and trellised roses. My father fixes everything to his own taste. When the bricks on the front stoop got tired-looking, he patched them, painted the whole stoop brick red, and then painted on white lines to replicate the mortar. A faux brick look over real bricks.

Entering by the front door, one has five locks to undo, two on the screen door and three on the wood door. Two steps and you are in the living room. On the walls: my mother’s oil painting of lilacs in a chinois vase on a Spanish table shawl in an over- sized faux gilt frame; a close-up view of a lilac bush that I painted; a replica of Renoir’s Bal a Bougival; and an oil painting of two girls surrounded by pigeons in Venice that my mother rescued from the trash. A large Sears photo of my children has slipped from its mat and shifted down in its plastic frame.

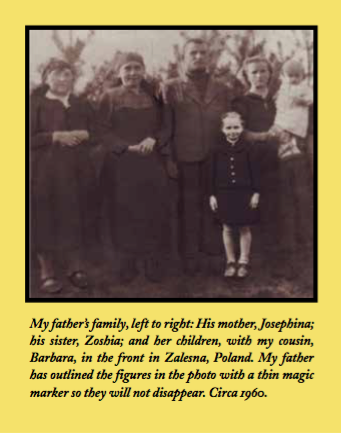

A photo of my father’s family has faded over the years. I notice that my father has outlined the figures in the photo with a thin magic marker so they will not disappear.

I want to cry whenever I see this, but I can’t.

My father has not seen any member of his family since 1945. Photographs and letters are exchanged periodically, and every few months my parents send used clothes and money in a corrugated box, tightly wrapped in a white cotton sheet, the seams of which my mother has hand stitched with rugged thread and a curved upholstery needle.

The Zenith TV set that I bought for my parents 20 years ago still maintains a prominent place in the living room. My brother bought them a VCR, and now they have a remote. Now, they don’t have to get up every time they want to turn the channel. This is progress. The velveteen sofa, encased in plastic slipcovers for years, is now raised up onto three bricks to facilitate sitting down and getting up.

The frayed, yellow-plaid Barcalounger, 20 years old, has two layers of floral-print fabric cushions. When I sit on the cushions, I am on the same plane as the arm rests. A little rocking back and forth, and the chair jerks into a reclining position from which it is impossible to sit up without assistance and good leverage.

Without the benefit of a how-to manual, my father has re-upholstered the three other chairs in the living room in deep gold-flecked, velvet. The short pile carpet is an aged, faded fuchsia and has a trail of assorted, colorful throw rugs and squares of patterned fabric so that one is able to walk the 21 steps from the front door through the living room, dining room and into the kitchen without ever stepping on the underlying rug. Underneath this throw-rug path, the original fuchsia color, in the patterns of all the different throw rugs, is still vibrant and clean. Just like new.

The dining room, adjacent to the living room, is packed with furniture, leaving just enough room to circumnavigate the table and chairs. The floor-to-ceiling credenza is filled with figurines in the French style, souvenir ashtrays from Niagara Falls, a Statue of Liberty with a thermometer in the base, porcelain puppies connected with a little brass-chain leash, a crystal ball that snows on the New York skyline when you shake it, tumblers filled with pennies, wine glasses, dishes, crystal bowls filled with broken costume jewelry, and a chiming clock modeled after Big Ben. Next to that, my mother’s upright piano, the top of which is covered with a crocheted doily and crowded with family photographs, another Barcalounger, another TV set with remote, and a large wooden stereo console with a broken record turntable; it is used for storing 78 RPM records and old insurance and hospital bills.

The dining room table always had a plastic lace-patterned oilcloth table cover on it to keep the dust off; I tried to remove the tablecloth and discovered that the plastic had melted the lace pattern into the surface of the table. Money is kept in a pouch taped under the table. My dad reupholstered all the chairs in beige Naugahyde and nailed clear plastic caps under the chair legs to protect the fuchsia rug from chair-leg dents. In order to move a chair, you must lift it up and place the chair where you want it. No sliding movement is possible. This is very difficult to do if you are sitting on the chair. But we eat in the dining room only on Thanksgiving.

Occasionally, if my father didn’t like what my mother was watching on TV, he would move into the dining room Barcalounger and watch his own shows. The telephone chair and stand were located in between the living room and dining room. I could sit there with Pavarotti singing Tosca on my right and America’s Most Wanted playing on my left and talk on the phone in complete privacy.

Last on the tour, the kitchen. Four giant steps on the harvest- gold linoleum tiles that have nails hammered into some of the curling corners, past the refrigerator, past the sink and stove, and you are out on the back patio with the aluminum web chairs. The Formica marbled kitchen table is set against the wall so that there is room for only three chairs. We are a family of four. Someone is always missing. The table is loaded with various small boxes containing all the medications that my parents ingest every day. We often take our plates into the living room and eat dinner while watching TV.

I ask my father to tell me his story.

“Dad, you know I have been writing down Mom’s history for a few years now. Mom says you were the youngest of three children, with an older brother, Janek, and a sister, and that you were born in Zalesna, Poland, near Lodz. Tell me what it was like for you when you were a child.”

My father’s eyes harden. “What do you want to know for? It’s no use. I don’t want to tell you my story. Mommy likes to tell stories, and tell the stories. I have no story. The rest is finished. Foolish stories. Don’t bother me, please. It’s gone, it is over.”

The intense comfort of familiarity mixes with the intense discomfort of intimacy.

I suddenly remember that there are many things I need to do that require me to leave the house for long periods of time. I am filled with guilt and remorse that I don’t spend enough time with my parents, that I know so little about them that I should have asked about, but it is impossible. Like walking on the throw rugs, I am unable to lift up all the layers of fear and loss.

I break speed limits on my three-and-a-half-hour drive back to Boston.

Beverly Sky was born in a DP camp in Salzburg in 1947. For 17 years she has been working on her manuscript, Remnants: Piecing Together the Stories, in conjunction with the memoir- writing program at the Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences.