Sarah Seltzer

Second Wave Feminism Comes Crashing Back

It’s common, if reductive, to describe American feminism as having come in waves, the first of which fought for the franchise at the turn of the century, the second of which, 50 years later, emerged from civil rights and anti-war movements to challenge sexism in society and our laws.

It’s common, if reductive, to describe American feminism as having come in waves, the first of which fought for the franchise at the turn of the century, the second of which, 50 years later, emerged from civil rights and anti-war movements to challenge sexism in society and our laws.

The third wave was associated with the 1990s and punk culture, with being individualistic, choice-oriented and fond of sex, and with the daughters of feminists like Rebecca Walker (Alice was her mom) literally calling their mothers to account for being too doctrinaire.

Today, feminism is so culturally ubiquitous that the “wave” seems more like an entire ocean, and it’s in these deep currents that many powerful second-wave thinkers have been swept back into prominence. This elevated status hasn’t always been theirs. In the early 2000s, immersing myself in “digital feminism”—a handful of blogs and websites—I found that second wavers were out of vogue, dismissed as essentialist for their focus on biological sex and elitist because their biggest lasting victories—work- place entry for professional women, abortion rights, liberation from Betty Friedan’s fabled mystique—seemed, decades later, bourgeois. Some of its radicalism had dimmed.

Rather than explicitly building on this preceding generation, many young bloggers took inspiration from the third-wavers of the 1990s—styling themselves as similarly “sex positive” and allegedly more inclusive of their queer, trans, and racially diverse sisters than previous generations had been.

Some of this generational conflict is inevitable—young people viewing predecessors as stuffy. Some of it is due to circumstance: bold second-wave ideas like universal daycare, wages for housework, a leveling of the sexual playing field and various forms of collectivism and radical disruption never fully took hold, after all. Furthermore, the wit and playful spirit of the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s got obscured by the prominence of the anti-pornography zeal many feminists demonstrated in the 1980s and the now-clichéd “man hating” and “bra burning” stereotypes that emerged in that decade’s anti-feminist backlash.

As one might expect, the same social forces that 1970s feminists fought against—embedded classism, racism, homophobia, sexism itself—had also erased much of their real work. The radical street theater groups, the lesbian communes, the women of color who saw housing as the urgent feminist issue, common cause made between professional women and the rights of the women they hired in their homes, the underground abortion providers, the democratization of specialized gynecological knowledge—all these constituted the “wave” too. Yet over time, their contributions were less celebrated.

Meanwhile, the edgier ideas of the movement’s marquee thinkers, a great many of whom were Jewish, remained too hot to touch: relentlessly questioning heterosexuality itself, the sanctity of the family, the institution of motherhood, the possibility of sexual equality, the workplace as a site of liberation and the devaluing of “care work.”

Time has rolled forward. Young bloggers and activists had kids, or began to climb the fabled corporate ladder, and came up against barriers. Politically, the optimism and activism of the Obama era gave away to what we have now: an admitted serial groper in power, a series of #MeToo allegations that are in some cases so depraved it feels like even the most strident young feminists underestimated the pervasiveness of sexism baked into the very structures of our lives.

It is far from a coincidence that, in the last five years or so, younger feminists have been publicly revisiting the written work of their foremothers—in some cases, their actual mothers—reading their wisdom in new anthologies, or exploring their lives and ideas in long articles and symposia. Joyce Antler’s 2018 book Jewish Radical Feminism gathers together dozens of these earlier thinkers, writers and activists, noting that for many, the specific subject of their Jewishness rarely came up, even during consciousness-raising sessions that included discussions of identity.

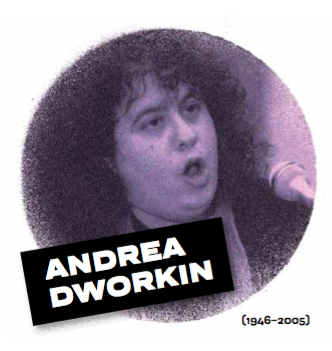

A new generation of Jewish feminists has been poring through their works. As Michelle Goldberg wrote in a 2019 New York Times column about the unexpected resurgence of interest in the late Andrea Dworkin, seemingly the epitome of “man-hating” feminism rejected by younger women, “the obscene insult of Donald Trump’s victory…seems like something sprung from Dworkin’s cataclysmic imagination, that America’s most overtly fascistic president would also be the first, as far as we know, to have appeared in soft-core porn films.”

“I think Trump’s victory marked a shift in feminism’s relationship to sexual liberation,” Goldberg continued. “As long as he’s in power, it’s hard to associate libertinism with progress.”

Dworkin’s comeback, sealed by an anthology called Last Days at Hot Slit (its title Dworkin’s own), is only one of many opportunities for younger feminists of all stripes to begin to sift through the ideas of their predecessors. As a third-wave icon, Riot Grrl musician Kathleen Hanna, told an interviewer: “We’re not going to keep moving forward if we don’t look at people’s ideas from the generation before and say, ‘This part is totally interesting, and this part totally pisses me off ’. We should be critiquing, but we don’t need to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

In doing this sorting, we may find much that makes us cringe based on today’s standards—especially on gender identity, race, and sexuality. And yet, without the caveats and considerations that make internet-era feminist writing occasionally feel rote, the prose often sings. In these earlier writers, energy shines through: sweeping ideas, imaginative leaps and, animating it all, anger—brilliant, beautiful anger that resonates strongly with the rage we feel today. It’s the anger of invention, and diagnosis, and unchartered territory. Yes, we can improve on that anger, and focus its target. But we can also learn from it. We have to.

Reading or re-reading what follows—choice quotations and excerpts from five Jewish writers, roughly of the Second Wave, rediscovered or elevated in recent years—you’ll encounter provocative, resonant, and prescient thinkers.

Grace Paley (1922–2007)

ON WHAT MEN NEED TO DO

“So men—who get very pissed at me sometimes, even though I really like some of them a lot—men have got to imagine the lives of women, of all kinds of women. Of their daughters, of their own daughters, and of the lives that their daughters lead. White people have to imagine the reality, not the invention but the reality, of the lives of people of color. Imagine it, imagine that reality, and understand it. We have to imagine what is happening in Central America today, in Lebanon and South Africa. We have to really think about it and imagine it and call it to mind, not simply refer to it all the time.”

“Of Poetry and Women and the World,” reprinted in A Grace Paley Reader: Stories, Essays, and Poetry. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2017.

ON ADOPTION AND THE SEPARATION OF FAMILIES AFTER VIETNAM

“Many women truly believed that the American care and ownership of these babies would be the only way their lives would be saved. But most women were wild at the thought of the pain to those other mothers,the grief of the lost children. They felt it was a blow to all women, and to their natural political rights. It was a shock to see the world still functioning madly, the world in which the father, the husband, the man-owned state can make legal inven- tions and take the mother’s child.”

“Other People’s Children” from Ms. Magazine, in A Grace Paley Reader.

ON ANTI-ABORTION FOES

“What they really want to do is take back ownership of women’s bodies. They want to return us to time when even our children weren’t our own; we were simply the receptacles to have these children…abortion isn’t what they’re thinking about; they’re really thinking about sex. They’re really thinking about love and reducing it to its most mechani- cal aspects—that is to say, the mechanical fact of intercourse as a specific act to make children in this world, and thinking of its use in any other way as wrong and wicked. They are determined to reduce women’s normal sexual responses, to end them, really, when we’ve just had a couple of decades of admitting them.”

“The Illegal Days” (1991), in A Grace Paley Reader.

ON “HAVING IT ALL”

“…this is really where the women’s move-ment is very sharp and really good—but this really has been put over on [women], this idea that…you have to do it perfectly: you have to get them to the right school, and you have to get them to the right nursery school. Well, you don’t. First of all, you fool yourself if you think that you’re so goddamn important, you know? You’re just not that important. You’re important, but the world is bringing them up and insofar as the world is bringing them up—so that if you have a boy, he’s liable to be sent off and murdered in Africa or someplace like that— you better pay attention to the world too. It’s all related.” Interview in The Boston Review, September 1, 1976.

Ellen Willis

Ellen Willis

Ellen Willis was a rock critic and essayist who co-founded Redstockings with Shulamith Firestone but later found

her sister feminists’ anti-porn critiques censorious. Her daughter, Nona Willis Aronowitz, and a generation of female music critics and musicians, have helped give her work renewed prominence, anthologizing it most recently in The Essential Ellen Willis.

ON “FAMILY VALUES” & WOMEN’S WORK

“Capitalists have an obvious stake in encouraging dependence on the family…If people stopped looking to the family for security, they might start looking to full employment and expanded public services. If enough parents or communal households were determined to share child rear- ing, they might insist that working hours and conditions be adapted to their domestic needs. If enough women refused to work for no pay in the home and demanded genuine parity on the job, our economy would be in deep trouble.”

“The Family: Love It or Leave It” from The Village Voice (September 1979), reprinted in The Essential Ellen Willis. University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

ON MARRIAGE

“The modern celebration of romantic love muddled the issue: now we want mar- riage to serve two basically incompatible purposes, to be at once a love relationship and a contract. We exalt love as the highest motive for marriage, but tell couples that of course passion fades into ‘mature’ conjugal affection. We want our mates to be faithful out of love, yet define monogamy as an obligation whose breach justifies moral outrage and legal revenge. We agree that spouses who don’t love each other should not have to stay together, even for the sake of the children; yet we uphold a system that makes women economic prisoners…”

“The Family: Love It or Leave It.”

ON WOMEN AND SHOPPING

“For women, buying and wearing clothes and beauty aids is not so much consumption as work. One of a woman’s jobs in this society is to be an attractive sexual object, and clothes and makeup are tools of the trade. Similarly, buying food and household furnishings is a domestic task; it is the wife’s chore to pick out the commodities that will be consumed by the whole family. Appliances and clean- ing materials are tools that facilitate her domestic function. When a woman spends a lot of money and time decorating her home or herself, or hunting down the latest in vacuum cleaners, it is not idle self-indulgence (let alone the result of psychic manipulation) but a healthy attempt to find outlets for her creative energies within her circumscribed role.”

“Women and the Myth of Consumerism” from Ramparts (1970), in The Essential Ellen Willis.

ON THE CRISIS OF TOXIC MASCULINITY

“If you undergo the painful process of renouncing the ‘feminine’ aspects of your humanity and follow your father into manhood (and what choice do you have, really?) you will share in the spoils of the superior half of the race. Now, as men, they nd that the spoils are far more meager than expected. No wonder they feel betrayed.”

“How Now, Iron Johns?” from The Nation, December 13, 1999.

Shulamith Firestone was a writer and activist who was a founding member of three radical-feminist groups: New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Perhaps her best known work is the 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution which argues for the complete divorcing of reproduction from biology, via “bottle babies.” Raised an Orthodox Jew but estranged from her parents, she suffered from mental illness and isolation later in life.

Shulamith Firestone was a writer and activist who was a founding member of three radical-feminist groups: New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Perhaps her best known work is the 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution which argues for the complete divorcing of reproduction from biology, via “bottle babies.” Raised an Orthodox Jew but estranged from her parents, she suffered from mental illness and isolation later in life.

ON SMILING

“In my own case, I had to train myself out of that phony smile, which is like a nervous tic on every teenage girl. And this meant that I smiled rarely, for in truth, when it came down to real smiling, I had less to smile about. My ‘dream’ action for the women’s liberation movement: a smile boycott, at which declaration all women would instantly abandon their ‘pleasing’ smiles, henceforth smiling only when something pleased them.”

“Down with Childhood” from The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1970.

ON EXAMINING CULTURE

“Feminists have to question, not just all of Western culture, but the organization of culture itself, and, further, even the very organization of nature. Many women give up in despair: if that’s how deep it goes they don’t want to know.”

“The Dialectic of Sex” from The Dialectic of Sex.

ON THE NECESSITY FOR LEGAL ABORTION

Those bodies belong to us. We don’t have to appear in your courts proving our mental incompetence to you before we can avoid forced childbearing! …we will no longer submit to your definitions of what we should or should not be or do to become truly feminine in your eyes. For unless we have a part in creating the laws which govern our fate, then we will refuse to follow those dictates and laws.”

Notes on the First Year: New York Radical Women, 1968 (“$.50 to women, $1 to men”) cited in The Cut, “The Life and Death of a Radical Sisterhood,” November, 2017.

ON BIOLOGICAL SEX

“The end goal of feminist revolution must be, unlike that of the rst feminist movement, not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.”

“The Dialectic of Sex.”

ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS

“It is naive to believe that women who are not politically seen, heard, or represented in this country could change the course of a war by simply appealing to the better natures of congressmen…”

Notes on the First Year.

ON BEING PUT ON A PEDESTAL

“To be worshipped is not freedom.”

“The Dialectic of Sex.”

Adrienne Rich was a major American poet whose

verse and prose writings on feminism, motherhood and sexuality have long been treasured by younger women. Her nonfiction has recently been compiled as Essential Essays: Culture, Politics and the Art of Poetry.

ON HETEROSEXUALITY

“The assumption that ‘most women are innately heterosexual’ stands as a theoretical and political stumbling block for many women. It remains a tenable assumption, partly because lesbian existence has been written out of history or catalogued under disease; partly because it has been treated as exceptional rather than intrinsic; partly because to acknowledge that for women heterosexuality may not be a ‘preference’ at all but something that has had to be imposed, managed, organized, propagandized and maintained by force is an immense step to take if you consider yourself freely and examine heterosexuality as an institution is like failing to admit that the economic system called capitalism or the caste system of racism is maintained by a variety of forces, including both physical violence and false consciousness.”

“Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Experience” (1980), reprinted in Essential Essays. W. W. Norton, 2018.

ON MALE “RIGHTS”

“[W]hen we look hard and clearly at the extent and elaboration of measures designed to keep women within a male sexual purlieu,it becomes an inescapable question whether the issue we have to address as feminists is not simple ‘gender inequality,’ nor the domination of culture by males, nor mere ‘taboos against homosexuality,’ but the enforcement of heterosexuality for women as a means of assuring male right of physical, economical, and emotional access.”

Essential Essays.

ON CHILDREN

A movement narrowly concerned with pregnancy and birth which does not ask questions and demand answers about the lives of children, the priorities of government; a movement in which individual families rely on consumerism and educational privilege to supply their own children with good nutrition, schooling, health care can, while perceiving itself as progressive or alternative, exist only as a minor contradiction within a society most of whose children grow up in poverty and which places its highest priority on the technology of war.”

Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, W. W. Norton Company, originally published in 1976.

ON MOTHERHOOD AS AN INSTITUTION

“The mother’s battle for her child—with sickness, with poverty, with war, with all the forces of exploitation and callousness that cheapen human life—needs to become a common human battle, waged in love and in the passion for survival. But for this to happen, the institution of motherhood must be destroyed.”

Of Woman Born.

Andrea Dworkin was a radical feminist, activist and writer particularly known for her critique of pornography, including proposed legislation to outlaw it. Much of her work on sex, sexual assault and domestic violence has been met with resistance and sometimes scorn. Her essays have recently been compiled in Last Days at Hot Slit.

Andrea Dworkin was a radical feminist, activist and writer particularly known for her critique of pornography, including proposed legislation to outlaw it. Much of her work on sex, sexual assault and domestic violence has been met with resistance and sometimes scorn. Her essays have recently been compiled in Last Days at Hot Slit.

ON ENDING PATRIARCHY

“As women, we must begin this revolutionary work. When we change, those who define them- selves over and against us will have to kill us all, change, or die. In order to change, we must renounce every male definition we have ever learned; we must renounce male definitions and descriptions of our lives, our bodies, our needs, our wants, our worth—we must take for ourselves the power of naming. And most importantly, in freeing ourselves, we must refuse to imitate the phallic identities of men. We must not internalize their values and we must not replicate their crimes.”

“The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door” from Our Blood (1976), reprinted in Last Days at Hot Slit. MIT Press, Semiotext(e), 2019.

ON BEAUTY

The technology of beauty, and the message it carries, is handed down from mother to daughter. Mother teaches daughter to apply lipstick, to shave under her arms, to bind her breasts, to wear a girdle and high heeled shoes. Mother teaches daughter concomitantly her role, her appropriate behavior, her place. Mother teaches daughter, necessarily, the psychology which defines womanhood: a woman must be beautiful, in order to please the amorphous and amorous Him. What we have called the romantic ethos operates as vividly in 20th-century America and Europe as it did in 10th-century China.”

“The Herstory,” from Woman Hating, 1974.

ON “LOCKER ROOM TALK”

“It is in male bonding that men most often jeopardize the lives of women. It is among men that men do the most to contribute to crimes against women. For instance, it is the habit and custom of men to discuss with each other their sexual intimacies with particular women in vivid and graphic terms. This kind of bonding sets up a particular woman as the rightful and inevitable conquest of a man’s male friends and leads to innumerable cases of rape. Women are raped o en by the male friends of their male friends. Men should understand that they jeopardize women’s lives by participating in the rituals of privileged boyhood. Rape is also effectively sanctionized by men who harass women on the streets… who act aggressively or contemptuously towards women; who tell or laugh at misogynistic jokes; who write stories or make movies where women are raped and love it; who consume or endorse pornography; who insult specific women or women as a group; who impede or ridicule women in our struggle for dignity.”

“The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door.”

ON “EQUAL PAY”

“The argument that work outside the home makes women sexually and eco- nomically independent of men is simply untrue. Women are paid too little. And right-wing women know it. Feminists know that if women are paid equal wages for equal work, women will gain sexual as well as economic independence. But fem- inists have refused to face the fact that in a woman-hating social system, women will never be paid equal wages… Feminists appear to think that equal pay for equal work is a simple reform, whereas it is no reform at all; it is revolution. Feminists have refused to face the fact that equal pay for equal work is impossible as long as men rule women…”

The Politics of Intelligence” from Right Wing Women. Perigee, 1983.

Please wait...

Please wait...